by Mark Harvey

After we get back to our country, black clouds will rise and there will be plenty of rain. Corn will grow in abundance and everything [will] look happy. –Barboncito, Navajo Leader, 1868

My idea of a fun evening is listening to the oral arguments of a contentious dispute that has reached the Supreme Court. As much as I disagree with some of the justices, I must admit that almost all of them are wickedly sharp at analyzing the issues—the facts and the law—of every case that comes before them. I don’t always get how they arrive at their final votes on cases that seem cut and dried before their probing inquiry. But most of them can flay a poorly presented argument with all the efficiency of a seasoned hunter field-dressing a kill.

So it was with the recent hearing on Arizona v. The Navajo Nation, heard before the court this year on March 20. At stake, in this case, is what responsibility the US government does or doesn’t have in formally assessing the Navajo Nation’s need for water and then developing a plan to meet those needs. The brief on behalf of the Navajo people, Diné as they prefer to be called, puts the case in stark and unmistakable terms: “This case is about this promise of water to this tribe under these treaties, signed after these particular negotiations reflecting this tribe’s understanding. A promise is a promise.”

The promise referred to in the brief refers to a promise made about 150 years ago when the Diné signed a treaty in 1868 with the US Government to establish the Navajo Reservation as a “permanent home” where it sits today. The treaty is only seven pages long and it promises the Diné a permanent home in exchange for giving up their nomadic life, staying within the reservation boundaries, and allowing whites to build railways and forts throughout the reservation as they see fit. A lot of things were left out—like water rights.

It’s hard to imagine that the Navajo signed the treaty with a clear understanding of what all it entailed. To begin, the negotiations involved two interpreters and three languages. The interpreter for the US Government spoke English and Spanish and the interpreter for the Diné spoke Spanish and Navajo. So the back-and-forth negotiations went from English to Spanish to Navajo, then Navajo to Spanish to English. On top of that, it’s impossible to believe that the men representing the Diné understood the juridical language not their own, the multiple hereins, thereons, hereafters sprinkled throughout that treaty signed on that fateful June day in Fort Sumpter, New Mexico Territory.

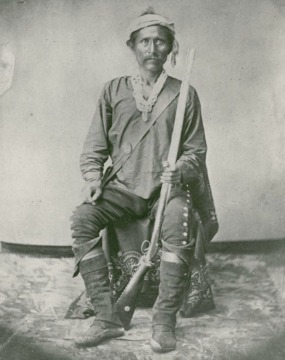

The Indian leaders who signed the treaty—Little Wolf, Sorrel Horse, The Man in the Sky, White Crow, and all the others—did so under what had to have been extreme duress. Throughout the 1860s, the US government had marched thousands of Diné off of their ancestral lands to internment camps in Bosque Redondo near Fort Sumner in what is today New Mexico. All accounts of the camps in Bosque Redondo paint a picture of terrible living conditions and profound suffering.

The thousands of Diné removed and interned were desperate to get back to their lands and probably would have signed nearly any treaty to return home. The treaty makes mention of the right to farm on 160-acre plots within the reservation and even a hundred dollars’ worth of seeds and agricultural implements per family to get started. It also lists a fifteen-thousand-dollar grant from the US government for the nation to buy sheep and goats. But it makes no mention of water sources or water rights. I’m not the best farmer in the world, but it seems to me that a treaty that encourages farming in what is a vast desert should say something about how to irrigate your corn or water your livestock. Something was lost in translation.

The Navajo Nation, a sprawling 17 million acres, covers parts of northeast Arizona, southern Utah, and western New Mexico. Its western boundary is defined by the Colorado River. The nation has a desertic climate, only receiving between 12 and 16 inches of water per year.

Today, in part from the 1868 treaty’s failure to include water in the deal, the Diné living on the Navajo Nation are perhaps the most water-starved people in the United States. Average water use per capita there is a meager seven gallons per day—less than a tenth of what an average American consumes. For perspective, an eight-minute shower uses about 20 gallons, and a load of laundry consumes between 25 and 40 gallons. Nearly a third of Diné households do not have running water.

There’s a chance that the Navajos would have had no standing whatsoever in this case were it not for the 1908 Supreme Court decision titled Winters v United States. At issue in the Winters case was whether Indians on the Fort Belknap reservation in Montana had water rights despite none being clearly listed in the 1888 treaty that created the reservation. The court concluded that because the intention behind creating reservations was to allow Indians self-sufficiency, water rights were implied in the treaties. Their reasoning—fairly elementary, really—was that to be self-sufficient, farmers or stock growers require water. So the justices concluded that water rights were implied in the creation of any reservation and that those rights had the seniority of the date the treaty was signed. Needless to say, the Winters decision gave tribes far more leverage in water disputes.

Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, a group called Western Water Users and the other parties that joined the lawsuit against the Navajo, are jealously protecting their water on the mainstream of the Colorado River. In their briefs and oral arguments they state that water rights on the Colorado River have long been settled and that if the Navajo win this case, it will threaten an already overextended water regime.

Unless you’re in a news blackout, you probably know that the Colorado River is already oversubscribed by the seven western states that share its waters under an agreement written in 1922. There simply isn’t enough water to grow cotton in Arizona, lettuce in California, casinos in Nevada, alfalfa in Utah, peaches in Colorado, supply drinking water in New Mexico, and good fishing in Wyoming. This past year, the various states’ fight to protect their water reached a war-footing quality as represented by the ever-so diplomatic headline in The Cowboy State Daily: “Wyoming Getting Screwed in Colorado River Compact.”

What’s vague about the case, at least to me, is if the Diné are actually asking for water rights directly from the main stem of the Colorado River or just an assessment by the federal government of the nation’s needs and then a plan to meet those needs—again based on an implied promise from the 1868 treaty. The attorneys for the Diné say they are not asking for a quantifiable volume of water yet, only a study and a plan. One of the petitioners trying to protect their rights on the Colorado River call this a “procedural end-run” and state “If its lawsuit were successful, it would inevitably reduce the amount of water available to other users in Arizona, with cascading negative consequences for the stability of water rights in that state and elsewhere.”

The heading on the court’s order that lists the warring parties looks like one of those unfair battles in the 19th century between the US cavalry and a small poorly armed Indian tribe. It is the Navajo Nation, plaintiff, against the US Department of Interior, Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior, the United States Bureau of Reclamation, the Bureau of Indian Affairs plus twelve very powerful intervenor defendants such as the State of Arizona, the Arizona Power Authority, and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

The lopsided battlefield and two of the parties fighting against the Diné’s quest for water illustrate the bizarre relationship between Indian Nations and the federal government. After all, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland is a member of the Laguna Nation so one might assume she would direct her agency to advocate for the Indians. And having the Bureau of Indian Affairs squarely against the Navajo Nation in a court of law is another example in a long line of cases where that agency acts more like the Bureau Against Indian Affairs.

I side with Indian nations on nearly every issue because what we have today in terms of tribal governance is still a vestige of the 19th century. When you look at what Indian nations can and can’t do to advocate for their own interests, the word that comes to mind is paternalism. For the Indians do not own their land, the federal government owns their land and is meant to act as trustee. The reason a reservation is called a reservation is because the land has been reserved in a federal trust on behalf of the Indians. As trustee, the federal government is meant to have a fiduciary responsibility for the welfare of Indians. But in this case with precious water at stake, the federal government has an obvious conflict of interest—ensuring that its other major water users are not threatened. It’s very strange to see various cases of The Bureau of Indian Affairs or the Department of the Interior to be fighting legal battles against Indians. I’m not sure what a good analogy is, but what if your landlord was both in charge of keeping up maintenance on your house and also assigned to represent you in a court case if you claimed the roof was leaking?

I don’t know what it takes to give the Indian nations back their autonomy and sovereignty and “permanent homes” that are truly home, but it’s a long, rocky journey fraught with every misstep available. Some tribes speak of the sanctity of the circle or the hoop and how if the hoop is broken, the culture is broken. We did our bloody utmost to break the hoop and did a pretty good job of it. Whether it was forced marches off ancestral lands, killing sixty million buffalo, or massacres of entire villages, our history with Indians is an ugly one. What is to answer for what DH Lawrence called “hard” and “isolate” souls of early American settlers? It could be our early migration, a desperate people moving west—ever west—under the urging of Horace Greeley and his like, poor pioneers believing the rain followed the plow, Mormons pushing push-carts across the Red Desert, and sodbusters building straw bale houses in the paths of Kansas tornados. Maybe it was the inhospitable plains, deserts with cruel winters and little water, the saltbush, the creosote bush, and the ephedra.

But there is an awesome fluidity in the affairs of humans that beleaguers our understanding of time and space. Archeologists suggest that the Diné are of Athabaskan ancestry out of Alaska and Canada and that they began to inhabit the American southwest in about 1,400 AD. They had some 450 years of living as nomads in the southwest before they were forced to march to Bosque Redondo by the American government. And it’s been about 150 years since the Diné signed a treaty under duress and juggled around in three different languages and a lot of strange treaty-speak to that March day a few weeks ago when the Diné were represented by one of the best attorneys in the country. Shay Dvoretzky, their lead counsel and a graduate of Yale Law School, has argued 17 Supreme Court cases prior to this one and is considered a top lawyer by his peers, law journals, and clients. The case presented by the Navajo is sophisticated, carefully structured, and since it passed muster in the ninth circuit and is now being heard by the Supreme Court, obviously has merit. Win or lose, the awesome efforts by the Navajo to get enough water to live beyond seven gallons per person per day shows a ferocious tenacity expressed over one and a half centuries.

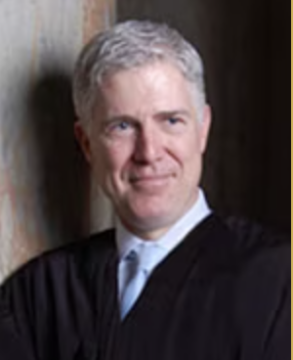

Having listened to the oral arguments and read some of the briefs, I think this case is going to be a nail-biter. Optimistically I think Gorsuch will join Kagen, Sotomayor, and Jackson in support of the Diné. That’s only four of the nine justices. Of the remaining five justices, I think there’s a slim chance Roberts will vote in favor of the Navajo too. But don’t take my opinion to the bookies in Vegas. This one is hard to predict and I’m probably wrong about Roberts. I do think Gorsuch has real compassion for the Indians based on his cross-examination of the solicitor general representing the federal parties. At one point, Gorsuch says with what sounds like anger, “If you’d just answer my question. Could I bring a good breach-of-contract claim for someone who promised me a permanent home, the right to conduct agriculture and raise animals, if it turns out it’s the Sahara Desert?”

Gorsuch also joined Ginsberg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagen in McGirt v Oklahoma in 2020 and even wrote the majority opinion. That case was centered around whether McGirt, a member of the Seminole tribe and accused of a heinous sexual assault while on the Creek Nation, should be tried by the state of Oklahoma or the tribal courts along with the federal courts. At issue was whether the federal government had ever disestablished The Reservation of the Five Civilized Tribes (which would give the state of Oklahoma jurisdiction). The reservation makes up lands that cover half of eastern Oklahoma and even part of Tulsa. Gorsuch begins his opinion with, “On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise. Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever.” Later in his opinion, Gorsuch wrote, “So it’s no matter how many other promises to a tribe the federal government has already broken. If Congress wishes to break the promise of a reservation, it must say so.” Wham!

If you’ve lived long enough, you’ll realize that life doesn’t move in the linear storybook progression that would be so much more comfortable, but that it can double back upon itself in strange dream-state ways. Some of these doubling backs happen in a lifetime, but others happen over the course of decades or hundreds of years and sometimes they involve entire nations and peoples. That a man of Punjabi descent is the prime minister of England today would have the upper class of England from the 19th century choking on their gin and tonics. That a black man with a Muslim name would one day be president of the United States would have the old Kentucky slaveholders, with their bloody lashes and their auction blocks, choking on county-distilled bourbon. Things haven’t come full circle yet for the Navajo people but their position before the Supreme Court with world-class representation and, what to me, seems like a sympathetic justice who otherwise votes with the most conservative decisions, brings hope. Hope that the Diné people will get enough water to fulfill the promise of a treaty signed long ago. Hope that the broken hoop can be made whole.