by Chris Horner

Less disappointing than life, great works of art do not begin by giving us all their best. —Proust

…for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life. —Rilke

Everything demands our attention. A ceaseless stream of electronic information and entertainment flows through and around us. Attention spans shrink, and we struggle to focus on anything for more than a few minutes. Entertainment waits on every click, as does ennui. Paradoxically, we may come to want the things that we cannot have in an instant, that demand our time and patience before they will reveal all they have to offer: the art that demands that we slow down. To really appreciate those productions of culture that can refresh us, make us think, immerse us in beauty, even strike us with terror, takes time. Art that is challenging often requires this of us. This can be true of more ‘popular’ art forms too, if they have the kinds of layers that take time to be appreciated. Their advantage over what I’m calling ‘slow art’ is they give us an immediate sugar rush that keeps our attention on them (exciting narrative, easy to recall musical ‘hook’ etc) and which encourage us to return to them again and again. There’s nothing wrong with that. But not all art will do that, or not as often and as easily. Slow art, if it is great art, demands our time and patience before it will reveal all it has and can be to us. We should welcome this, for not only does this art often reward us most for our patience, but the practice of paying attention is itself, understood rightly, a kind of joy. There is an art that can offer us a world if we will but attend.

Taking Time

When we take the time to engage with Slow Art, we are forced to change our pace and pay attention. We have to be present in the moment and actively participate in the experience. This can be challenging, especially in a world that is constantly pulling us in different directions. However, it is also incredibly rewarding. Distraction, though, is the enemy of this kind of deep satisfaction. When we are distracted we are not able to engage with the art on a deeper level, and we miss out on many of the nuances and subtleties that make it so powerful. Eliminating distraction takes conscious effort. But we must make that effort.

Attention

Attention

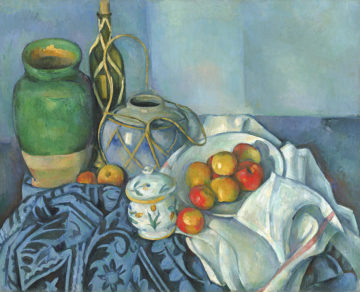

The most popular painting in London’s National Gallery is Constable’s The Hay Wain. I remember being told that the average time spent in front of it is 30 seconds. Whether this is true or not, it sounds plausible. Large galleries, full of great works can encourage a ‘gulp it down’, approach that really does nothing for one’s experience art, let alone one’s aching feet. And the determined effort to really look is going to exhaust our eye and mind before long. So it would surely be better to spend much longer over far fewer works, rather than rushing from room to room. Maybe just one work will do. I was reminded of this at the recent very large exhibition of the works of Paul Cézanne in London’s Tate Modern art gallery. Cézanne was a master at capturing the essence of a subject, but his paintings require the viewer to look beyond the surface and see the underlying structure and form. This can be a challenging task, but those who are willing to take the time to really engage with his work can gain a deeper understanding of the beauty and complexity in the art. The way the geometry seems to defy physics in his still lives, the way the fruit and the jugs are anything but still, the colour and movement that they propose as the life of things as perceived by an intelligent eye. You can’t see all this in in two minutes, even if you use your phone to ‘capture’ what is before you. You have to surrender to the thing before you, even if it takes a long time and many visits. Even if it takes a struggle with your own desire to be distracted by the Next Thing.

Listening

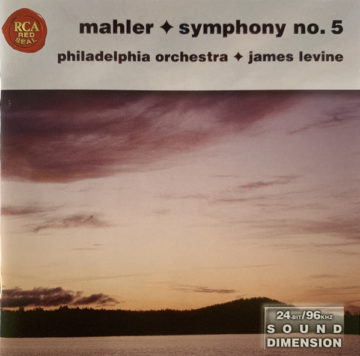

Still less can you take in any seriously complex music in just a quick listen. Take Gustav Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, for instance: it is in three parts, five movements, and takes about 70 minutes to listen to. Is this too long? Compare it to a sports match or a Netflix original: its not that different when it comes to duration what marks it out is the quality of attention required over more than an hour. Here as elsewhere, repetition is one’s friend: what there is becomes gradually clearer as we return to it. But with music, there is the temptation to let it play in the background while one does something else. This should be resisted. There is too much going on in the music. In the second movement of the symphony, for instance, there is an attempt to end – literally -on a triumphant note. A brass chorale blazes out a victory that somehow is derailed by the music itself as it collapses into silence. But in the work as a whole we get to understand the chorale and its place as it returns in the last minutes of the whole work, this time fully affirmed. Well, nearly, as there is still nuance in Mahler’s handling of the end of the symphony, still some irony, something alongside the final apotheosis that seems to hint at other things. So the long arc of the symphony’s movements is in someways a journey from dark, from mourning, to light. But, like life itself, only from some perspectives and in some lights. Discovering this for oneself is in my experience, richly rewarding.

Still less can you take in any seriously complex music in just a quick listen. Take Gustav Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, for instance: it is in three parts, five movements, and takes about 70 minutes to listen to. Is this too long? Compare it to a sports match or a Netflix original: its not that different when it comes to duration what marks it out is the quality of attention required over more than an hour. Here as elsewhere, repetition is one’s friend: what there is becomes gradually clearer as we return to it. But with music, there is the temptation to let it play in the background while one does something else. This should be resisted. There is too much going on in the music. In the second movement of the symphony, for instance, there is an attempt to end – literally -on a triumphant note. A brass chorale blazes out a victory that somehow is derailed by the music itself as it collapses into silence. But in the work as a whole we get to understand the chorale and its place as it returns in the last minutes of the whole work, this time fully affirmed. Well, nearly, as there is still nuance in Mahler’s handling of the end of the symphony, still some irony, something alongside the final apotheosis that seems to hint at other things. So the long arc of the symphony’s movements is in someways a journey from dark, from mourning, to light. But, like life itself, only from some perspectives and in some lights. Discovering this for oneself is in my experience, richly rewarding.

Reading

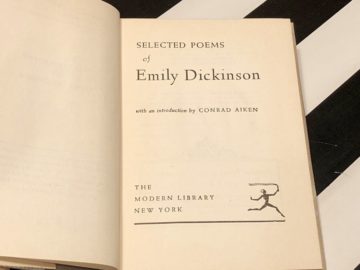

Something similar applies to poetry. This has nothing to do with how many lines a poem has. Short lyric pieces can, like a photographic negative in a dark room, only slowly come to light, and blossom in the consciousness of the reader. To read a series of poems quickly is a bit like eating crisps, fine for a while but not very nourishing. There is an art to reading well means bringing one’s whole self to the experience, to being open emotionally and cognitively to everything that is there, which may not show itself on the first scan of the lines. There are layers of meaning in Emily Dickinson, for instance, that only really reach us if we are willing to dwell with the poem. The first stanzas of this poem, for instance:

Something similar applies to poetry. This has nothing to do with how many lines a poem has. Short lyric pieces can, like a photographic negative in a dark room, only slowly come to light, and blossom in the consciousness of the reader. To read a series of poems quickly is a bit like eating crisps, fine for a while but not very nourishing. There is an art to reading well means bringing one’s whole self to the experience, to being open emotionally and cognitively to everything that is there, which may not show itself on the first scan of the lines. There are layers of meaning in Emily Dickinson, for instance, that only really reach us if we are willing to dwell with the poem. The first stanzas of this poem, for instance:

There’s a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons,

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes.Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference

Where the Meanings are…

None of this can be meaningfully paraphrased into simple prose. The meaning(s) is resistant to quick assimilation.

Layers

Slow art has layers. And this is why it requires time and effort. We should see this as a good and necessary thing. If this is a kind of obstacle in the way of easy assimilation then it is an obstacle that is integral to the value of the thing itself. The mind is calmed, or disturbed, or made exultant by the art that rewards us for our goodwill and our capacity to take our time. As Nietzsche says – and I cannot resist giving this great aphorism in full, as it may be one of the very best things he ever wrote:

One must learn to love.— This is what happens to us in music: first one has to learn to hear a figure and melody at all, to detect and distinguish it, to isolate it and delimit it as a separate life; then it requires some exertion and good will to tolerate it in spite of its strangeness, to be patient with its appearance and expression, and kindhearted about its oddity:—finally there comes a moment when we are used to it, when we wait for it, when we sense that we should miss it if it were missing: and now it continues to compel and enchant us relentlessly until we have become its humble and enraptured lovers who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it.— But that is what happens to us not only in music: that is how we have learned to love all things that we now love. In the end we are always rewarded for our good will, our patience, fair mindedness, and gentleness with what is strange; gradually, it sheds its veil and turns out to be a new and indescribable beauty:—that is its thanks for our hospitality. Even those who love themselves will have learned it in this way: for there is no other way. Love, too, has to be learned.

(Nietzsche, The Gay Science, aphorism 334)