by Michael Liss

In the America I see, the permanent politician will finally retire…. We’ll have term limits for Congress. And mandatory mental competency tests for politicians over 75 years old. —Nikki Haley, age 51, announcing her candidacy.

Yes, she did. Nikki Haley went there. Of course, her ostensible target is America’s best-known octogenarian (the guy with the malaprops and the Ray-Bans), but it could not be ignored that Former President Donald Trump tips the chronological scales at 76. Twenty months from now, shortly after the 2024 election, Joe will either be a jubilant 82-year-old; a grim, packing-the-china 82-year-old; or a wistful I-could-have-won-if-I-ran 82-year-old. Trump will be a 78-year-old Donald Trump—with title, without title, still a Donald Trump. In November of 2024, barring anything traumatic, these two will be whatever luck, genetics, and environmental factors cause them to be. If one of them also happens to be President-elect, then their issues will become our issues through 2028. That is something to ponder.

Haley may have been a bit blunt, in the process angering not only Former Guy, but perhaps potential supporters in Congress (roughly 1/3 of the Senate is at least 70), but the discussion of whether Dad should still be driving at night (or riding on Air Force One) is not an unreasonable one. We aren’t some sleepy principality somewhere, ruled by a hereditary monarch whose most impactful decisions involve whether we should subsidize domestic clock-making. This is a challenging world, and Dad needs to be up to it. There’s a terrific Ron Brownstein interview in The Atlantic of Simon Rosenberg of the New Democratic Network. Rosenberg notes, “But with China’s decision to take the route that they’ve gone, with Russia now having waged this intense insurgency against the West, the assumption that…[Western democracy] is going to prevail in the world is now under question…. [I]t’s birthing now… a different era of politics, where we must be focused on two fundamental, existential questions. Can democracy prevail given the way that it’s being attacked from all sides? And can we prevent climate change from overwhelming the world that we know?”

Those are big questions to answer, and most of us, unless our politics occupy a fringe, should be deeply invested in the answers. They are also truly multi-generational, with the biggest stakeholders being the younger cohorts. My Boomer generation can offer something in the way of experience and expertise, but we’ve had a lot of time to work on solutions, and our results speak for themselves—we absolutely must give multiple seats at the table to younger voters. And, at some point, and that point may have already been reached, my Boomer Generation needs to follow Nancy Pelosi and to give way entirely. “Senior leadership” does not automatically mean “Senior” leadership.

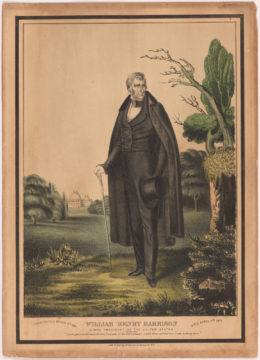

History tells us that, until very recently, we have always implicitly understood that age does matter. For 140 years, the gold standard of Presidential old was William Henry Harrison, who didn’t listen to his mother, failed to dress warmly at his Inauguration, spoke for two hours (take that, Bill Clinton), and died of pneumonia 31 days later.

Harrison was empirically old (68), although not old enough to qualify for Nikki Haley’s competency test. Was he that rare? Actually, he was. From Lincoln in 1860 to FDR, not a single first-time taker of the Oath of Office was over 56. For those of us who used to be 56 and are now edging closer to 68, we can be honest enough to affirm that’s a big difference.

Why? Presidents are a little like baseball pitchers; while there are freaks of nature (Nolan Ryan, Justin Verlander), it’s very difficult to sustain velocity as you age, and velocity can’t be entirely replaced by craft. Reagan still had his fastball at 69, but by the time his second term came to an end, his remaining abilities were in question.

Biden himself was the equivalent of the “Crafty Lefty” who came out of the bullpen to retire one menacing batter. Part of many Democrats’ and swing voters’ reticence about his potential 2024 candidacy isn’t a function of his policy chops—he’s done a credible job as POTUS. It’s a deeper concern over his political ability to take on an entire line-up of free-swinging right-handed hitters. The Party is going to need leadership in 2024. It’s also going to need in it in 2025-28. Biden can’t realistically play the role of elder statesman if he’s still sitting in the Oval Office, and he certainly can’t do it if he runs and loses—he will take the blame, justifiably, for insisting on running a second time.

It is not impolite or disloyal to discuss this. More than any President in our memory (except, perhaps Gerald Ford for entirely different reasons), Biden was and continues to be seen as a transitional figure. The voters hired Joe to be much like what Europeans call a “caretaker” leader—someone who, in the moment, seems uncontroversial and…temporary.

That leaves Biden in an odd place. He doesn’t now have, nor has he ever had, a large natural constituency. There’s a reason why virtually every Presidential hopeful (and Biden “hoped” for half a century) remains nothing more than a quadrennial candidate: there’s something missing from their makeup, and the public senses it. Think back to the also-rans in the 2020 primaries, and you will see a lot of future also-rans. Also-rans generally only become President because they are first selected as Vice Presidents. And Presidents don’t choose running mates who are more charismatic and more electable than they are. Certainly, President Obama didn’t.

It’s just not easy to transition from second banana to the most powerful person in the country, and, more lately, the world. Unless you are truly exceptional (and why would you be if you are Veep?), you tend to be seen as a placeholder. History shows this in several ways—in who filled the job, as well as in their party’s and the public’s estimation of them. The Vice-Presidential stigma doesn’t always wear off.

The 19th Century brought us VPs John Tyler (for William Henry Harrison), Millard Fillmore (for Zachary Taylor), Andrew Johnson (for Lincoln), and Chester Alan Arthur (for Garfield). Not only didn’t any of these four get elected, on their own, to a succeeding Presidential term, but none of the four even got their Party’s nomination to run for it.

The 20th Century brought a different variant: the Vice President who succeeded to the office of the Presidency through the death or retirement of the President, got their party’s nomination, but then won only one full term on his own. Teddy Roosevelt succeeded McKinley, then won on his own, retired, and jumped back in four years later. His third-party candidacy handed the election to Woodrow Wilson. Truman came back to defeat Thomas Dewey in 1948, but then was gently, but firmly, shown the door for 1952, in part because of concerns about his age (66). Lyndon Johnson, who won a landslide victory in 1964, was then unable to control a fractious Democratic Party for 1968, and announced he wouldn’t run again. George H.W. Bush lost convincingly to Bill Clinton after 12 years of fairly aged GOP control. Add Gerald Ford, who filled the balance of Richard Nixon’s term, and then lost to Jimmy Carter.

None of the five saw a successor from the same political party. The only Vice President who succeeded to the Presidency, won a term on his own, and then saw his Party retain control was Calvin Coolidge, who became President when Warren Harding died, won in 1924 in a landslide, then kept his promise not to run again—he thought 10 years too much, although the public certainly would have given him the last four. Fellow Republican Herbert Hoover replaced him.

What about Presidents (whether directly elected or by death of their predecessor) who lost a bid for re-election, but tried a second or third time, as Trump is attempting?) There are only four, and only one (Grover Cleveland) had success in his come-back: Martin Van Buren defeated William Henry Harrison (that guy) in 1836, lost to him in 1840, and got roughly 10% of the popular vote in 1848. Millard Filmore, who replaced Zachary Taylor in 1850, was not renominated in 1852, left his party to run as a “No-Nothing” in 1856, and got 21% of the popular vote and Maryland’s 8 Electoral Votes. Cleveland defeated James Blaine, then lost to Benjamin Harrison (grandson of William), but managed to beat him in a rematch. The last of the four was Teddy Roosevelt, who lost in his disruptive 1912 campaign. Of the four, only Van Buren was over 60 at the time of his last campaign.

There really are no historical precedents that are fully applicable now. Trump will be older than Ronald Reagan was in his second term. Biden will be older than the State of Delaware. Trump wants to emulate Grover Cleveland, but Cleveland won the popular vote all three times, and Trump has lost it in both his elections and is deeply unpopular with a substantial portion of the electorate. Biden would be only the second Vice President to win the Presidency twice—the first was Nixon, which is not the best omen.

None of that necessarily means much of anything, if Biden and Trump both get their parties’ nominations. Here, perhaps we should thank Nikki Haley for putting something on the table that others have been hesitant to broach publicly. She’s framing it as a matter of age and competency, and those are critical points, but what she’s really getting at is that both men, for entirely different reasons, command too much support to be ignored or disrespected without consequence, but not enough to give them, and the ticket they head (including down-ballot) a clear edge in enthusiasm.

If Haley really moves the public debate, there are a lot of party professionals, both Republican and Democratic, who would be grateful because they would love to move on. There are even more voters who would gladly see neither man run in 2024. The polling data* and focus groups show it. Younger voters in particular want change—they are tired of the same old arguments that have no relevance to their futures. And while partisanship continues to rise, with local and state elections becoming increasingly nationalized, both candidate quality and the message emanating from the top is still critical to driving turnout.

What’s next? We can’t know yet. Holding the Presidency, as Biden does, gives him the possibility of creating indelible images. Biden’s secret trip to Kyiv, with its extraordinary cloak-and-dagger aspect, is a fantastic example of that. The story of him on the armored train passing through and into a war zone to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Zelenskyy demonstrates to the world (including our Western European allies) the power of simple ideas like freedom, and steadfast resistance to aggression. That the visit angered Putin and his supporters in the GOP is just a side benefit.

Incumbency is both blessing and curse. Its power of incumbency is not really transferable. Only Biden can use it, and if he steps aside, it loses potency. But with incumbency comes the terrible risk of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, to which both Herbert Hoover and Jimmy Carter can attest. Sometimes, the world just flies apart, and no amount of deftness will fix it right away, whilst everything you can think to do seems cursed.

Twenty months is a lot of time for things to go wrong, not just on the national and world stage, but also in the life of two men who were born in the 1940s. It’s also, as Nate Silver recently pointed out, not a lot of time. As much as we like to think in terms of plot twists in movies and television, they make for great screenwriting in part because they just don’t happen that often. There’s every possibility that, by Labor Day 2024, we will be locked into the same old arguments, with the same old guys. Going nowhere on the big issues and hoping, perhaps, for a Deus ex Machina.

That’s not going to work with those two existential questions posed by Simon Rosenberg: “Can democracy prevail given the way that it’s being attacked from all sides? And can we prevent climate change from overwhelming the world that we know?”

Much of the public knows this, and more will. We can’t wait to refocus the discussion for two years, much less see it stalled for six. The thing about time is that it often seems an inexhaustible quantity, until it’s gone.

Right now, it’s going.

*Some of the best non-partisan polling data comes from AP-NORC. Contact my friend Marjorie Connelly at [email protected] to be added to their list.

*About the title: It’s the first line of the song “My Get-Up-And-Go Has Got Up and Went,” sung by Pete Seeger and the Weavers.