by Marie Snyder

A student asked, “How many bad actions does a good person have to do before becoming a bad person?”

The notion of good and bad people raises the image of final judgment at the pearly gates. We have a scale somewhere with our actions added incrementally to one side or the other until there’s a tipping point, or sometimes there’s just that one unspeakable act that slams one pan to the ground requiring an inconceivable effort to budge it.

It’s possible that an infinite number of bad actions doesn’t make a person bad. I like to think that we’re all greater than the sum of our worst actions. We’re all just works in progress doing our best in this world, and it’s never too late to change our path. It sounds nice. But then I started to consider some real people who appear to have unlimited selfishness as well as a cold indifference to the suffering they cause to others. Can we call them bad people until we see some movement towards redemption?

If we’re going to use the scales to slot people, for the time being at least, we have to figure out what constitutes a good or bad action. A bad action harms, of course, but how much and how intentionally and how directly all muddle up the calculations. And what do we have to do to be good? Michel Montaigne has an interesting take on this in “Of Cruelty.” If we’re good by nature and upbringing and do good automatically, then it’s good, but not virtuous. There’s a higher level of good that happens when it involves an internal struggle, which is what indicates an intentional act.

I cycle or walk rather than drive, and I was over 50 before finally succumbing to the demands of my children to live like normal people and buy a car. This gets me kudos with environmentalists. However, I hate the smell of cars, the cost, and driving, and I was raised by environmentalists. So, by nature and by upbringing not having a car was the path of least resistance even in our car-obsessed culture. It’s not that biking to work isn’t a good thing to do, and laudable, but it’s not virtuous when it’s by inclination.

To evaluate goodness, it’s not enough to look at behaviours. Montaigne writes,

“When we judge of a particular action, we are to consider the circumstances, and the whole man by whom it is performed, before we give it a name. To instance in myself: I have sometimes known my friends call that prudence in me, which was merely fortune; and repute that courage and patience, which was judgment and opinion; and attribute to me one title for another, sometimes to my advantage and sometimes otherwise.”

It’s just my dumb luck that hating cars is seen as praiseworthy in this particular time and place.

Because I was, like Montaigne, born with a generally peaceful disposition and “cannot see a chicken‘s neck pulled off without trouble,” and I was trained to be considerate of others and selfless through parental reminders and that withering look of disappointment that flashes before my eyes when I consider the wrong action (although it’s not always effective), and I live in a relatively law-abiding society, it’s harder to be actually virtuous.

To rank goodness, scenarios can help to weed out what we prioritize. Imagine a businessman, walking home from work through a park, who suddenly sees a little girl drowning in the lake. There appears to be nobody else around, and he’s a very good swimmer.

- He struggles with the decision to help because he doesn’t want to get his suit wet and dirty (or we can add that he recognizes her as his daughter’s nemesis even), but he consciously decides to dive in to save her.

- He automatically dives in. He doesn’t make a conscious decision. It’s the obvious option for him.

- He thinks of the reward he might get or maybe fame from a segment on the news later, or even a medal, and dives in.

- He sees an opportunity to use the girl in his sex trafficking ring, and dives in to abduct her, but then a cheering crowd appears on the shore; the child and her parents are reunited and his nefarious plans destroyed.

They all have the same end result, but we can see a hierarchy of goodness from the intentions. Montaigne’s essay suggests that #1 is virtuous, and #2 is merely good. However, when it comes to good and bad people, we might recognize #2 as the better person because he didn’t have to think about it. The fact that #1 paused for an internal dilemma makes him of dubious moral character: Since he paused this once, he might not make the admirable choice in the future.

Scenario #3 is harmless, but the intention is self-serving. Many of us would think along the same lines, a flash of “I’ll be a hero!” as we kick off our shoes, so we’re likely to accept a moment of selfishness leading to a beneficial result. He did save her, after all. Finally, #4 is clearly bad because of the intention to harm regardless of the identical result. Sometimes, “All’s well that ends well,” but the nature of the intent here is too heinous to overlook. We can’t judge without knowing intentions, which are nearly impossible to access in others, even sometimes in ourselves.

A similar type of scenario involved my dearly departed dad.

In the late 1930s, my dad was awarded a medal for bravery for risking his life to save another man from drowning. I’ve seen the medal and the newspaper clipping that recalls his courage. The paper says that he saw a man struggling in a river and drove straight in to save him, nearly drowning himself. But I was told a different story straight from the source.

He was in his late teens and had a part-time job driving a milk truck. He had to make his run every day at four a.m.. Not one to get up early, he’d just stay up late, go to work, then get to bed as the sun rose. There were only two rules: he couldn’t drink or have a passenger.

One early morning, after a night on the town, he was half in the bag when he started his route and happened upon a young man who needed a lift. Who doesn’t want some company when they’re tanked? The hitchhiker was very chatty and great company.

Unfortunately, between the inebriation and the distracting chatter, my dad drove straight into the Detroit River. He immediately swam for the dock, but, looking back, saw that his passenger couldn’t swim. My dad’s instinct was entirely driven by self-preservation. He knew that he’d be in big trouble if he let the guy drown, so he had to get the guy up on dry land. By his own admission, he rescued the stranger to save his own ass. When people came to investigate the commotion, the hitchhiker was fine, but my dad needed to be rushed to the hospital with water in his lung. Spectators made the assumption that he had driven into the river to save the man; the hitchhiker didn’t correct them, and a ceremony was set up to honour my dear father’s heroic deed.

This story was always told to us jovially. Put another way, though, in the context of today’s attitude towards drunk driving, is my dad a bad person for breaking the rules, almost killing a man, and then accepting an award for it? Should he have been made to atone for the intention of his actions? Is his ranking affected by the good he did or even by society’s attitude towards drunk driving at the time?

This story clarifies Montaigne’s insistence on identifying circumstances as well as intention when making a judgment call. At the time, drunk driving wasn’t vilified like it is now. When I was a teenager in the 80s, even, police came to break up a bush party I had attended. As they cleared us all out from a farmer’s field, they didn’t stop any of the staggering 16-year-olds from getting in their cars to drive home. It’s not that they didn’t know the possibility of inebriated driving causing harm, but they saw it as a low risk. It took another couple decades of work to embed a general awareness that drunk driving is unconscionable. Deaths were seen as unfortunate accidents as if the lack of intention removed culpability. It’s hard to even imagine thinking that way now.

There’s a fifth drowning girl scenario to add to the previous four, of course. #5. The businessman walks past the lake and pretends not to notice the girl. He makes it home at the usual time. The little girl dies.

Is #5 more or less bad than the child trafficker? Which one can be more easily forgiven? One is an intention with an active harm involved: abduction and sexual abuse, but no harm was caused. The other is indirect harm resulting in death.

Is he a bad person for just minding his own business?

Later Montaigne tries to make sense of horrific cruelty, people who “invent unusual torments and new kinds of death, without hatred, without profit, and for no other end but only to enjoy the pleasant spectacle.” If we set aside the truly wicked, assuming they’re rare, a close second that’s more common might be harming for profit, and then allowing harm for profit or even convenience.

If we know that our inaction will cause harm, that knowledge makes it bad, but the escape clause of plausible deniability makes it harder to judge and easier to rationalize. People can all too easily feign ignorance in order to try to bury any guilt or avoid prosecution. This happens with genocides through starvation or deaths from denial of the basic necessities to life, like has happened in some long-term care homes through the pandemic. It happens when people are robbed of the quality of their life or health in horrific stories about big box stores, or lack of abortion access, or Covid policies that put people in harm’s way. It happens when homes are lost and entire areas of land rendered uninhabitable from business as usual strategies under climate change.

However, I was trained to be mindful of the effect my actions have on others, be considerate and never wasteful, but some people have been raised to get ahead. They learned to do whatever it takes to win the game and not worry about their effect on others who are less deserving. If causing harm to others is the bottom line for morality, then being encouraged to step on others on the way up is not just a different upbringing, with a different moral code and values, but, in fact, immoral child rearing. But, if we’re considering the person’s whole story when judging, and they were raised to step on others, (and their parents were raised that way, and so on, and so on) then should we forgive them for they know not what they do?

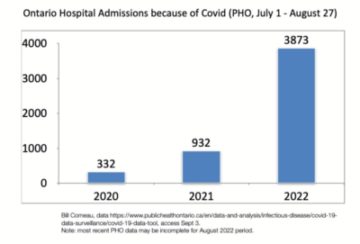

With Covid, politicians who removed mandates and isolation periods must know that fewer masks will cause more deaths. Some are suggesting Covid is over despite packed hospitals. In Ontario this past summer, more people have been hospitalized and died of Covid than in the previous two summers combined. More Canadian lives have been lost to this virus than in WW2, and in half the time. The policy makers in many places have relinquished responsibility, and we don’t have decades to shift the Overton window as was done with drunk driving.

We’ve agreed, mainly, that if someone causes harm when inebriated, they’re still at fault because it was their choice to start drinking. But what if someone causes harm because they’ve naively followed bad advice? Ignorance of the law is no excuse, but what about ignorance of the nature of the lawmakers?

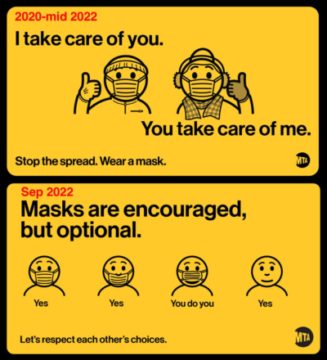

Within our current culture, people who don’t wear a mask in public, who risk the lives of others, are like the drunk drivers from over forty years ago. When the Public Health response to the pandemic is “You do you!” then we can’t judge people as bad for being led to believe that it’s all over, despite the continuing illness, disability, and death being left in our wake, iff they really don’t know about the true risks of the disease.

However, surely people ought reasonably to know of the potential harm and that a third of cases are asymptomatic, so any of us could have it and spread it without feeling sick. That information was everywhere in the beginning of this mess. But we’re very good at convincing ourselves that we’ll continue to be lucky and make it home unscathed once again. Willing ourselves to be blind to uncomfortable information, like pretending we don’t see the drowning girl, is causing harm.

Scenario #6. You don’t wear a mask. Several people around you are getting sick at once, but you don’t feel sick at all so you carry on, but start wearing a mask just in case. Eventually that one friend who doesn’t see anyone but you, convinces you to do a test, and it’s positive. You realize you’ve been the hub that caused many illnesses. Where does that rank? Is there guilt involved or an apology necessary if a friend ends up permanently disabled? But we thought it was over!

Covid is taking far more lives than drunk drivers and sober drivers, but it’s a misfortune that we’ve convinced ourselves we play no part in causing. Without warnings or heartfelt messages about the deceased from our leaders, have they removed the possibility for moral reasoning to occur? Like my dad in the 30s, it’s just a big “Whoops!” and a funny story if everyone lives, or an unfortunate mishap if they die. Being convinced that masks aren’t necessary is in our best interest if we want to continue thinking well of ourselves and avoid the inconvenience, so there’s an impetus to believe that Covid’s over despite the cost to life and livelihood of those around us. Just like climate change.

This judgment of good and bad behaviours is an important way society establishes shared values. Judging or absolving people, however, is all but impossible if we are to take their circumstances into consideration, as Montaigne would have us do. There are too many factors, many unknowable, affecting a refusal to save someone or reduce potential harm to others or even actively harm for profit. Our task is to continue discussing the errors in our behaviours in order to inch society towards at least being good, if not virtuous, or else die trying.