by Carol A Westbrook

We live in an artificially-colored world, filled with added color in our homes, our clothing, our toys, our hair and even our food! We take this plethora of colors for granted. By comparison, the natural world is bland and almost monotone, except for small patches of brightly colored flowers or birds.

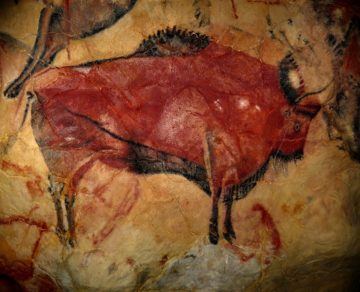

Ever since prehistoric times, man has had the urge to add color to his surroundings by expressing himself in paintings. Imagine a caveman picking up a charred piece of wood from his fire and drawing a picture on the cave wall. Later he added colors made from colored clays and stones that he picked up near the cave…and so painting begins. Some of the oldest of these ancient paintings were located deep in caves so carefully hidden that they lie undisturbed for millenia. One of the most famous of these are the paintings in the caves of Lascaux, in Southwestern France, depicting over 2,000 figures of animals and men, as shown in this detail of a bison colored with red ochres.

The Lascaux cave art was created over 17,000 years ago, using paint made from local sources.

The colored clays used to paint the cave walls were iron-containing rocks and clays known as ochres. Ochres are ubiquitous, as iron is the fifth-most abundant element in the earth. The colors of ochre stones vary from muted yellow to browns and reds; no doubt the caveman artist tried burning his colored stones and found that he created even more colors. This is due to reduction of the iron ore within the stone, resulting in the production of iron oxide or rust. The caveman’s paint colors, or his palette, included yellow ochre, red ochre, raw umber, raw Sienna and burnt Sienna. Burnt Sienna? No, this is not the name of a color derived from burning the medieval town of Sienna, but rather from burning a brown stone found near Sienna, which when burnt gives and even darker brown.

This palette of the stone age painters has remained the basis of painting over the ages and into the modern era. Ochre (seen on the right) was mined and traded, and by the time of the Greeks and Romans these pigments were available to artists so they didn’t have to mine them themselves. In the 18th century, large ochre deposits of many shades were found in the town of Vaucluse in Provence; these were mined for their ochre and processed to produce the pigments used by the great painters of the modern era, such as Edvard Munch’s Madonna, wearing a beret of Burnt Umber.

The last of these mines closed in 1950. Today, all the ochre pigments can be synthesized in the labs and used to color acrylic and oil paints, but the original names remain in use, and serve to remind us that our legacy as painters goes back to the beginning of humankind.

Yet one color stands out as being there at the very beginnings of art: black. Black has always been available, initially as charcoal from burned wood or bones, later as carbon graphite and other carbon pigments. To the present day, charcoal is used to sketch pictures, to draw outlines that then get filled with other colors, or to mix with other colors to darken the tint. Black is the color that it is because it absorbs light, and thus does not reflect any colors. Surprisingly, all blacks may look alike but their differences are unmasked when they are mixed with other colors or used in a diluted form.

We often don’t think of black as a color, but recent controversies in the art world have changed that perspective. The “blackest black” is made by Surrey NanoSystems, and it is called Vantablack. It is made up of a series of sub-microscopic synthetic vertical tubes of carbon. These tubes trap light instead of letting it bounce off, and it is continually deflected between the tube so no light escapes. Vantablack absorbs up to 99.96 % of visible light. It was developed for use in painting stealth satellites but it has been used cleverly in installation pieces by Anish Kapoor. (Anish Kapoor is an installation artist, best known for his sculpture “Cloud Gate,” which is installed in Chicago and is known locally as “The Bean.”) Kapoor bought exclusive rights to this copyrighted color, and only he was allowed to use Vantablack in artworks. His first work with this color, Into the Void, is shown on the left.

This so enraged the art community, that his rival artist, Stuart Semple, commissioned “an even blacker black” and allowed its free use by the entire art community—except Kapoor! In 2019, a material was developed at MIT which absorbs 99.995% of light. These synthetic blacks are all made from carbon, that basic element made from burnt charcoal.

These synthetic blacks may be the most expensive colors in the world, but the most highly prized color is the blue made from the gemstone lapis lazuli. Blue is a rare color in nature; few animals and plants produce a clear blue pigment that can be used in paints to depict the sky. The Egyptians were the first to use powdered lapis lazuli as a paint pigment. Blue, along with gold, were considered divine colors, and lapis was used to paint eyes, hair and crowns of the kings, as well as the background skies of grave paintings in the Valley of the Kings.

The only source of this prized pigment were the mines of Afghanistan. Imagine the journey this stone had to take, by camel train, carts and ships, until it reached the Egyptian craftsmen. No wonder it was worth its weight in gold! Lapis Lazuli did not reach European painters until the 6th century. It produced a stunning, bright blue color that stands out on the canvas. This color is called ultramarine. Its popularity really took off in the Renaissance, as it was deemed to be Mary’s color. Wealthy patrons wanted it used in their religious artwork, and were willing to pay for it—it was worth its weight in gold at the time. An outstanding example of lapis lazuli paint is seen in this detail from The Ascension, attributed to Jacopo di Cione, below.

Artist: Attributed to Jacopo di Cione and workshop

Date made: 1370-1

Source: http://www.nationalgalleryimages.co.uk/

Contact: [email protected]

Copyright © The National Gallery, London

Afghanistan is still the major source of lapis lazuli in the world, but this precious stone is considered to be a conflict stone. Lapis mines and other mineral wealth are helping to fuel the war that has ravaged the country. Lapis lazuli has mostly been replaced by synthetic ultramarine, which produces a beautiful sky blue; lapis stone as a pigment would be prohibitively expensive.

Yellow pigment has many sources and just as many stories. The sources of yellow include cadmium and chromium pigments, which are relatively inexpensive compared to other paints, but many of them contain lead salts which are toxic. Chrome Yellow was a very bright yellow that was used by Van Gogh to paint his sunflowers and starry nights, while Lead Tin Yellow was the yellow of the day for artists such as Rembrandt and Vermeer.

One of the most interesting stories about yellow is that of Indian Yellow, a bright, almost fluorescent yellow which was non-toxic. Turner preferred this color for his sublime and sun-lit seascapes (on the right). Its

source was kept secret for many years, but was eventually found to be derived from the urine of cattle in the Bihar province of India fed only mango leave! This mistreatment of animals caused the pigment to be made illegal; it was completely abandoned in 1908. There are now synthetic replacements for this deep yellow-orange pigment that don’t require abuse of animals. The main components of Indian yellow, euxanthic acid and its derivatives, can be synthesized in the laboratory.

Indian yellow was not toxic, but other paint pigments were dangerous to the artists. Two are tied for most toxic paint: Lead White and Emerald Green, because of their widespread use. White Lead, a pigment of lead carbonate and sulfate, has been in use since antiquity. This paint is so highly reflective that it almost creates a glow on the canvas! Vermeer and other artists used it to create a special kind of light in his canvasses, as seen in The Girl with the Pearl Earring.

Although it was known for centuries to be poisonous, sometimes it was impossible to avoid contact, and many artists were in the habit of sharpening the tip of their paint brushes by licking them, a dangerous practice for lead-containing paint. The toxicity of white lead paint was recognized and accepted, as it was the only white in the palette that was available to the early European artists.

White lead was also used in industrial paints, creating a bright whitewash for walls, houses and other structures, including the fence painted by Tom Sawyer! White lead paint was not banned until fairly recently—1978 in the US—and it has been largely replaced by titanium white. Many artists still insist that there is no synthetic option that can completely replace Lead White. It can still be found in specialty paint suppliers.

Scheele’s Green, also called Paris Green, was invented in 1775 by Cal Wilhelm Scheele, a Swedish chemist. It was an artificial colorant made by combining a series of chemicals resulting in the production of copper arsenite. Copper arsenite is a highly toxic pigment which give a vibrant, jewel-like green color. Schele’s Green, and the loosely-related pigment Emerald Green, were very popular in Victorian England, and was used to color everything from candy, clothing and wallpaper to artist’s paints. Green dyed cloth was beautiful, but women who wore these dresses might suffer skin lesions, vomiting and bloody diarrhea, and in some cases cancer. Many seamstresses died from repeated exposure. On the left is a lovely green Victorian death dress, colored with arsenic. Napolean Bonaparte’s bedroom was painted in Scheele’s Green, and this is thought to have contributed to the gastric cancer which killed him. The Impressionist artists in particular were found of green and preferred a slight variant of this green, copper acetoarsenite, or Emerald Green, which was more stable (Scheele’s green tended to darken with age). Arsenic based paints were known to be toxic and by the late 19th century were banned over most of Europe.

There are so many other colors with fascinating stories that I could go on for pages! But the ochre mines of Italy have all closed; cattle in India are no longer fed a mango leaf diet, and the lapis lazuli mines in Afghanistan now produce smaller amounts of this gemstone, due to war and political corruption. There is little demand now for these natural pigments, as they have been replaced by less expensive synthetic options, whether they be oil, acrylic or water color paints. It is still possible to purchase natural mineral pigments or oil paints, but they are expensive, even if you mix your own.

If you look among your paint tubes or in your crayon box you will see that the historic paint color names are retained. For example painting with “burnt sienna” is preferred to painting with “Paint Color Index #PR102”. These wonderful names help us to keep alive the lore of the early painters, from the cavemen to Anish Kapoor, all of whom put beauty and color into our surroundings.