by Mark Harvey

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

Even Americans born well into the 20th century had a stoic quality and a modest sense of their own importance that seems to have been washed out of our culture. Not many WWII veterans left, but the ones I’ve met spoke about their battles at Normandy or in the South Pacific as just something that needed to get done. The people I knew who lived through The Great Depression said it was tough but made light of their own hardships.

Much of our citizenry today resemble loud spoiled children, whining and whingeing at every inconvenience, and trotting out opinions on the most complex matters—with zero formal training or any in-depth research. I fear that to other countries we look like one of those screaming toddlers having a fit in a very public place. Sort of an international cringe.

The recent melt-down over gas prices is a prime example of American petulance. Does the increase in gas prices affect the average American family? Yes it does. Are the fits over gas prices in proportion to the issue and do most Americans understand how gas prices are set? No and no.

There are lots of little stickers on gas pumps with an image of President Biden pointing at the price meter along with a caption saying, “I did that.” In the comment section of a May 18 article about gas prices in The New York Post, one person wrote, “Gas is 4.85 by me!! Thank you Joe!! And all the idiots that voted for this bs!!”. Another person wrote, “Nice job, Biden voters, you screwed us all!”

There are lots of little stickers on gas pumps with an image of President Biden pointing at the price meter along with a caption saying, “I did that.” In the comment section of a May 18 article about gas prices in The New York Post, one person wrote, “Gas is 4.85 by me!! Thank you Joe!! And all the idiots that voted for this bs!!”. Another person wrote, “Nice job, Biden voters, you screwed us all!”

The truth is, no matter the party, the President has little control of gas prices. There are lots of macroeconomic and microeconomic forces determining gas prices, but the guy sitting in the Oval Office has little to do with it. The price of gas at the pump is determined by four main factors: the price of crude oil, the cost of refinement, the cost of distribution and marketing, and taxes. The cost of crude oil makes up close to 60% of the price of gas and refinement makes up close to 17%. Those two elements really determine gas prices as taxes and marketing/distribution tend to be stable.

Theoretically gasoline prices should track the price of crude oil in a symmetrical fashion—when crude goes up, gas should go up and when crude goes down, gas should go down. Gasoline prices do tend go up symmetrically with oil prices but then only drift down slowly when oil prices go down. In the petroleum trade they call this the “rockets and feathers effect.” Gasoline prices shoot up but float down as gas station owners do everything in their power to keep the price up and only reluctantly lower it when forced by competition.

If you think the president determines gas prices, then why did gas go from roughly a dollar fifty a gallon when George W Bush took office to roughly $4 gallon when he left office? Bush wasn’t exactly a green president and went on a wild spree of opening up federal lands for drilling during his term. His Vice President, Dick Cheney, might as well have had Halliburton tattooed on his rump, so spare me the idea that restricted drilling has an immediate impact on gasoline prices. Currently there are roughly 10,000 unused drilling permits in the US alone.

The same goes for the Keystone XL pipeline: Even if it had been given the green light, we wouldn’t have seen its impact on the gasoline market for another 10 years and the impact would have been so marginal as to be unnoticeable. The pipeline doesn’t increase production but only creates a new path for it to get to market. And most of the tar sands oil going down that pipeline is meant for export.

What’s driven up the recent gasoline prices has more to do with economies recovering from COVID and people of all nations traveling, commuting, and leaving their homes in cars and airplanes. During the height of the pandemic, oil companies reduced production dramatically as did refineries when demand went down. For the first time in history, oil prices on the futures market in 2020 went negative : companies actually paid storage fees for their oil with the plummeting demand.

What’s driven up the recent gasoline prices has more to do with economies recovering from COVID and people of all nations traveling, commuting, and leaving their homes in cars and airplanes. During the height of the pandemic, oil companies reduced production dramatically as did refineries when demand went down. For the first time in history, oil prices on the futures market in 2020 went negative : companies actually paid storage fees for their oil with the plummeting demand.

The same companies have been slow to increase production and refinery capacity since the pandemic started. What are they afraid of? A recession? Or something bigger like a rapid transition to renewable energy?

The war in Ukraine has also affected gasoline prices due to the oil embargo on Russia. The response to the oil embargo is disproportionate. We import a small amount of crude oil from Russia—only about 3% of supply to our refineries. As crude petroleum is by far Russia’s biggest export, putting an embargo on it was a no-brainer in terms of trying to deter its invasion of Ukraine. But watching some Americans whine about how an oil embargo on Russia would affect their lifestyle with higher gas prices was truly a profile in self-centeredness.

The contrast between ordinary Ukrainians grabbing a gun, rushing to the front to risk their lives as they fight for their country, and Americans moaning about the price of filling up their Ford F150s is unsettling. The lack of imagination that some Americans have when it comes to a very dangerous moment on the European continent and the lack of commitment to make small sacrifices to help keep the Russians from invading the rest of Europe defines petulance.

I bring up the Ford F150 for a good reason: it is the best-selling automobile in America. And don’t get me wrong, the F150 is a decent truck and has its purpose. But according to an Edward’s study, most of the people who buy these trucks don’t need them. In a 2019 article for The Drive, Brett Berk notes that 75% of truck owners use their truck for towing one time per year or less and for off-road use one time per year or less. He notes that 35% of truck owners don’t even use their trucks for hauling loads.

Guess what the second and third best-selling vehicles in the US are? The Chevrolet Silverado and the Ram 1500. So millions of Americans driving big trucks they don’t use for truck things like towing and hauling burn up gobs of gasoline and then bitch and moan about the high price of gasoline.

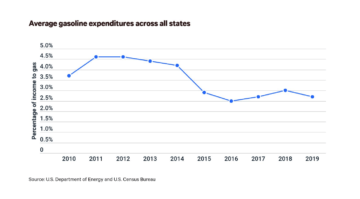

The median household income in the United States is around $80,000. Over the last 40 years, the average American household has spent between 2% and 5% of its income on gasoline, depending on the year and the price. Over the last 10 years that number averages out to about 3.5% of household income. Recent gas prices, if they had remained at their peak, would have cost American households on average an extra $1,200 per year. Stacked against the American propensity to buy big cars, avoid public transportation, and avoid spending money on infrastructure that supports public transportation, $1,200 seems like a small price to pay.

What’s really strange is that American households spend much more money on healthcare than on gasoline—more than twice as much—and yet resist basic measures to lower those costs. The resistance to the Affordable Care Act is a prime example. The ACA increased the number of insured Americans by tens of millions and particularly helped lower income households. According to a survey of 128,000 households done by Dr. Charles Liu at Stanford University, the ACA lowered healthcare costs for low-income households by nearly 20%.

And yet, some of the very same people who rage at the higher prices of gasoline also raged against more affordable healthcare because it was touted as “socialist.” But what’s more socialist than driving your Ford F150 down a four-lane interstate highway paid for by collective taxpayers. The definition of socialism is, after all, when the collective (read government) pays for and organizes the means of production. Like a highway for instance. Or a sewer system. Or a potable water system. Or a military.

And then there are things like pandemics that really cost everyone big money and of course millions of lives. It’s hard to put a number on what the pandemic cost the American economy but estimates way back in 2020 by Harvard economists put the number at $16 trillion. Through accelerated studies and lab work, every nation on earth concluded that three things would greatly reduce the spread of COVID and the consequences of getting COVID: masks, vaccines, and social distancing.

Massive studies have been done with hundreds of thousands of people to determine the efficacy of wearing a mask during the height of COVID and the studies concluded that the thin piece of cloth worn over nose and mouth save millions of lives worldwide. But to some Americans, wearing a mask was just too great a sacrifice. There are scads of videos on YouTube of red-faced Americans fighting their way to get into a shopping center or restaurant without a mask. They’re inevitably shouting about freedom and civil rights and discrimination.

Massive studies have been done with hundreds of thousands of people to determine the efficacy of wearing a mask during the height of COVID and the studies concluded that the thin piece of cloth worn over nose and mouth save millions of lives worldwide. But to some Americans, wearing a mask was just too great a sacrifice. There are scads of videos on YouTube of red-faced Americans fighting their way to get into a shopping center or restaurant without a mask. They’re inevitably shouting about freedom and civil rights and discrimination.

Even though the COVID vaccines have saved millions of lives and the health effects of repeatedly getting COVID are far worse than the side effects of the vaccines, many Americans refused to get one. Again the arguments were about FREEDOM, even though not getting a vaccine and thereby encouraging the virus has taken freedom from all of us.

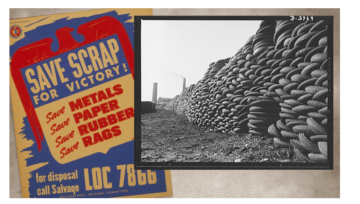

Compare the inconvenience of wearing a mask or getting a vaccine to what Americans sacrificed during WW II when almost everything was rationed: meat, butter, milk, sugar, and especially gasoline. The pandemic is a world war too, but since the enemy is an unseeable virus and the war involves epidemiology and virology, some Americans couldn’t be bothered to learn the science. And the basic science really isn’t that hard to learn.

I love this country but some of the things I love most are our great universities, a history of using good science to solve our problems, periods of time when the country came together as one such as during the Great Depression or World War II, and those who would have a studied and rational dialogue to solve our problems. What I don’t love are the loud, selfish Americans who bring problems on themselves and others by not taking the time or effort to thoroughly educate themselves about an issue, be it gas prices or a virus. We should have no more patience for that petulance.

Often you’ll see a giant pickup truck, that hasn’t towed or hauled anything in its life on the road, driving down a highway with one bumper sticker bemoaning high gas prices and another bumper sticker that says “Freedom.” That dude or dudette isn’t that free paying for all that unnecessary metal and all that unnecessary gasoline while driving down a highway built by the socialism they loathe. The bumper sticker should say “Confusion.”