Jeanne Erdmann in Nature:

Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them.

Zion Levy remembers the excitement that he and his daughter felt while poring over body scans in 2019, watching small black dots, representing melanoma metastases, shrink away and eventually vanish. They weren’t Levy’s scans. He didn’t even know who the scans came from, but he did share a connection with them.

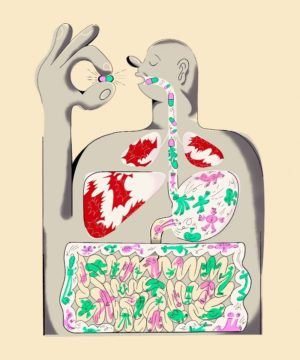

About five years earlier, Levy had been diagnosed with melanoma, but he was in remission thanks to a powerful immunotherapy called nivolumab. Because he had responded well to the drug, doctors at the Sheba Medical Center in Tel HaShomer, Israel, asked whether he would consider donating his stool — and the microbes inside — to possibly help others who had failed to respond or whose cancers had become resistant to treatment. He agreed to rigorous tests, blood draws and detailed questions about what he ate most (pizza). Levy made his donation, packed it into a cooler, and then called a taxi hired by the hospital. As with any transplant, travel time mattered. Doctors wanted the sample to arrive in less than 90 minutes.

Once there, Levy’s faeces were tested for pathogens, diluted, homogenized, centrifuged and sifted down to a refined microbial broth that could be freeze-dried and packed into capsules. Levy’s enthusiasm for the project convinced Ben Boursi, an oncologist at the Sheba Medical Center, who was leading the study, to share the anonymized scans of a recipient of his donated microbes. Today, that person has gone more than three years without evidence of cancer and has become a donor in a similar melanoma-treatment trial. It’s a legacy that Levy feels good about. “I am very proud that I can save lives. I would like to do it again,” he says.

More here.