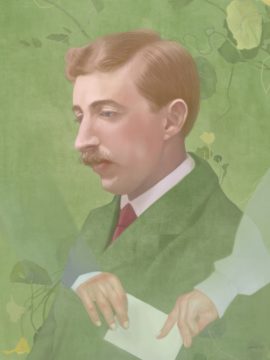

Alexander Chee in The New Republic:

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic 1971 review of Maurice in Commentary, “FORSTER AS HOMOSEXUAL,” in which she calls Forster’s posthumous revelation of his sexuality an “audacious slap in the face,” includes a decent one-paragraph summation of what we might call the first public Forster, the one the public thought they knew when they mourned him:

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic 1971 review of Maurice in Commentary, “FORSTER AS HOMOSEXUAL,” in which she calls Forster’s posthumous revelation of his sexuality an “audacious slap in the face,” includes a decent one-paragraph summation of what we might call the first public Forster, the one the public thought they knew when they mourned him:

He endured the mildest of bachelor lives, with, seen from the outside, no cataclysms. He was happiest (as adolescents say today, he “found himself”) as a Cambridge undergraduate, he touched tenuously on Bloomsbury, he saw Egypt and India (traveling always, whether he intended it or not, as an agent of Empire), and when his mother died returned to Cambridge to live out his days among the undergraduates of King’s. He wrote what is called a “civilized” prose, sometimes too slyly decorous, occasionally fastidiously poetic, often enough as direct as a whip. His essays, mainly the later ones, are especially direct: truth-telling, balanced, “humanist”—kindhearted in a detached way, like, apparently, his personal cordiality. He had charm: a combination of self-importance (in the sense of knowing himself to be the real thing) and shyness. In tidy rooms at King’s (the very same College he had first come up to in 1897) Forster in his seventies and eighties received visitors and courtiers with memorable pleasantness, was generous to writers in need of a push (Lampedusa among them), and judiciously wrote himself off as a pre-1914 fossil. Half a century after his last novel the Queen bestowed on him the Order of Merit. Then one day in the summer of 1970 he went to Coventry on a visit and died quietly at ninety-one, among affectionate friends.

His bachelor life, however, was not mild, and underwent several cataclysms—and “seen from the outside” barely admits what a closeted life could hide.

More here.