Adam Bradley in The New York Times:

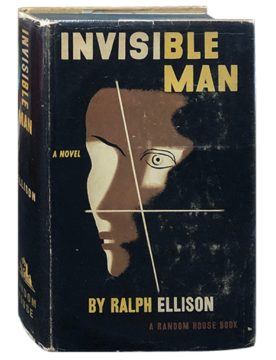

I first saw Ralph Ellison when I was 19 years old and he had already passed away. On a summer evening in 1994, he appeared to me in the attic of an old manor house on the campus of a small college in the Pacific Northwest. I had encountered him — just as I had Langston Hughes and Jane Austen and Geoffrey Chaucer — by more conventional means the year prior, as an attentive reader of his published work. I read Ellison’s 1952 novel, “Invisible Man,” for the first time as part of a class on African American literature and was drawn to his wise-foolish protagonist with whom, looking back now, I shared more than a passing resemblance: a young Black college student with vague aspirations for leadership who stumbles upon writing as a means of illuminating his identity. Nonetheless, Ellison — like Hughes and Austen and Chaucer — remained intangible to me, aloof, distanced both by time and by achievement.

I first saw Ralph Ellison when I was 19 years old and he had already passed away. On a summer evening in 1994, he appeared to me in the attic of an old manor house on the campus of a small college in the Pacific Northwest. I had encountered him — just as I had Langston Hughes and Jane Austen and Geoffrey Chaucer — by more conventional means the year prior, as an attentive reader of his published work. I read Ellison’s 1952 novel, “Invisible Man,” for the first time as part of a class on African American literature and was drawn to his wise-foolish protagonist with whom, looking back now, I shared more than a passing resemblance: a young Black college student with vague aspirations for leadership who stumbles upon writing as a means of illuminating his identity. Nonetheless, Ellison — like Hughes and Austen and Chaucer — remained intangible to me, aloof, distanced both by time and by achievement.

That could have been the end of it. But, as Ellison was fond of saying, “it’s a crazy country” — by which he meant that the diversity of the American experience often occasions unexpected confluences of people and circumstance. Soon after Ellison’s death, on April 16, 1994, at the age of 80, or perhaps 81 (evidence uncovered after his passing suggests he was born in 1913, not 1914, as he always claimed), Ellison’s wife, Fanny, called on their longtime friend John F. Callahan, my professor, to assume the literary executorship of his estate. Callahan asked me to be his assistant — to help him gather research, photocopy documents and sort materials — which explains why I ended up carrying shipments arriving from the Ellisons’ Riverside Drive address up a creaky staircase to the manor house attic on my college campus. My first task was to unpack the boxes and array the pages contained within across a long mahogany conference table, preparing them for Callahan’s inspection. Among the papers were drafts of Ellison’s unpublished second novel, around 40 years in progress; dot-matrix printouts from his computer, some with penciled edits; and handwritten notes scrawled on scraps of paper and on the backs of used envelopes.

More here.