Amber Dance in Nature:

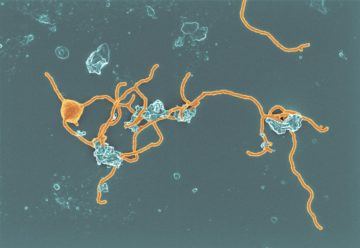

Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger.

Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger.

Archaea are more than just oddball lifeforms that thrive in unusual places — they turn out to be quite widespread. Moreover, they might hold the key to understanding how complex life evolved on Earth. Many scientists suspect that an ancient archaeon gave rise to the group of organisms known as eukaryotes, which include amoebae, mushrooms, plants and people — although it’s also possible that both eukaryotes and archaea arose from some more distant common ancestor.

Eukaryotic cells are palatial structures with complex internal features, including a nucleus to house genetic material and separate compartments to generate energy and build proteins. A popular theory about their evolution suggests that they descended from an archaeon that, somewhere along the way, merged with another microbe. But researchers have had trouble exploring this idea, in part because archaea can be hard to grow and study in the laboratory. The microbes have received so little attention that even the basics of their lifestyle — how they develop and divide, for example — remain largely mysterious

More here.