Early in the 20th century physicists restored us to time. That’s not how the story is generally told, but it is a good way to think about it. Having been restored to time, we must now realize that we are time travelers, not just Dr. Who, and his – but I believe it is now her, no? – assistant, but all of us.

Let me explain.

* * * * *

Let us begin by setting physics aside. Journey with me to a concert hall in Chicago in November of 1969. We are sitting next to Wayne Booth, a distinguished English professor at the University of Chicago who is an amateur cellist, and his wife, Phyllis. Though we do not know this, they are grieving the death of their son four months earlier as we are all listening to a performance of Beethoven’s string quartet in C-sharp minor. Here is how Booth described that performance in his book about his cello-playing, For the Love of It: Amateuring and Its Rivals:

Leaving the rest of the audience aside for a moment, there were three of us there: Beethoven… the quartet members counting as one….Phyllis and me, also counting only as one whenever we really listened …Now then: there that “one” was, but where was “there”? The C-sharp minor part of each of us was fusing in a mysterious way….[contrasting] so sharply with what many people think of as “reality.” A part of each of the “three” … becomes identical.

There is Beethoven, one hundred and forty-three years ago … writing away at the marvelous theme and variations in the fourth movement. … Here is the four-players doing the best it can to make the revolutionary welding possible. And here we am, doing the best we can to turn our “self” totally into it: all of us impersonally slogging away (these tears about my son’s death? ignore them, irrelevant) to turn ourselves into that deathless quartet.

How are we to think of this fusion Booth describes, himself with his wife, both with the four performers, and all of them, by implication, with Beethoven though the medium of his composition? What does that fusion, pushed to the limit, do with time? Is it possible, contra Heraclitus, to dip into the same stream time after time?

Consider the experience of Leonard Bernstein who, as a conductor, performed music written by others. One summer, during one of his residences at Tanglewood he was talking to conducting students about how he had to learn to bring himself under control. As a young conductor he once got so wrapped up in conducting that he was afraid he was having a heart attack. So, he explained to the students, he had to learn how restrain himself. Then Bernstein talked of ego loss:

I don’t know whether any of you have experienced that but it’s what everyone in the world is always searching for. When it happens in conducting, it happens because you identify so completely with the composer, you’ve studied him so intently, that it’s as though you’ve written the piece yourself. You completely forget who you are or where you are and you write the piece right there. You just make it up as though you never heard it before. Because you become that composer.

What are we to make of this statement, which he has made on other occasions? Did he literally become the composer – Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler, whomever? If so, could he have talked off the podium, out of the concert hall, and into the streets of eighteenth century Vienna? No, surely not. But what could he have meant?

* * * * *

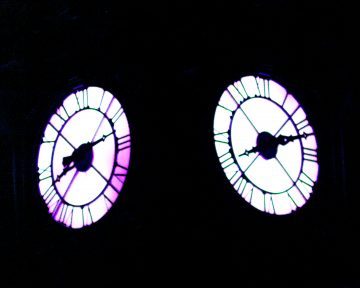

Strange creatures that we are, many of wear electromechanical amulets, aka wristwatches, which mark the passage of time down to the second, and often less. The time we so mark is, in some contexts, known as clock time. Certainly, in this context that is what I will call it.

These amulets are conceptually linked to a scheme that conceives of time as linear. This line of clock time extends back into the past to the beginning of the universe and forward until, well, whenever. Time is a line, moment after moment after moment after moment, etc., a containing in which events float, or a frame through which we examine them.

At the same time, there are these myths and stories of time as circular, not to mention Nietzsche’s notion of the eternal return. But what if time really were circular? Or, at least, not linear? How could that be? Could the presence of those linearizing amulets make us insensitive to temporal circularity?

That question became very real to me when I was working on Beethoven’s Anvil, where I discuss the incidents in the previous two sections at greater length. There I had to think about the brain and its states. And that is very tricky.

I decided to follow the work of late Walter Freeman, a Berkeley neurobiologist thought about brain states like a physicist thinks about the state of, say, a volume of gas. In this way of thinking the state of a physical system is a function of the state of each component of that system. So, the state of some volume of gas can be specified by noting the position and velocity of each molecule. If there are 100 trillion molecules in some volume, then you need the position and velocity for each of those molecules. Practically speaking, though, you don’t; that information isn’t available. We have no way of measuring the state of a volume of gas with that precision. But the underlying math is about that kind of object, position and velocity for each particle.

What happens if we think about brains in those terms? First we have to identify a unit component. The choice is not an arbitrary one, but we don’t know enough about the brain to be sure just what the appropriate unit object is. The individual neuron often plays this role, but one might choose, instead, the synapse (a connection between neurons). For our purposes it makes no difference. Either way, there are a very large number of such unit objects. We have no way of directly counting the neurons in the nervous systems, but estimates put the number at roughly 86 billion with an average of 10,000 synapses per neuron.

To specify the brain’s state at a given moment in clock time we need to know the state of each unit component, such as a neuron. One convenient way to do this is to say that a neuron is either firing or it is not. So it can have two states. Neurons are complicated things; each is a living cell with the full complement of machinery that that requires. There’s a lot more to a neuron that whether or not it’s firing.

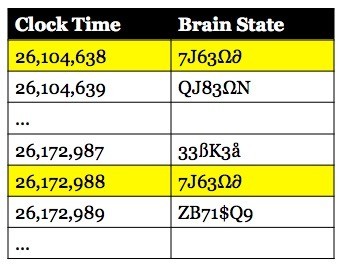

So, assume that we’ve to a way to characterize and measure a brain’s at a moment in time (that is, a sufficiently small interval). What if, while measuring someone’s brain states, we observed something like the table at the right.  In the left column we’re numbering the measurement intervals as they pass by in clock time. In the right column we’re keeping track of brain states as they flip by. Notice that one brain state, 7J63Ω∂, repeats, occurring first at clock interval 26,104,638 and then later at clock interval 26,172,988. What do we make of that? Only that the brain has somehow returned to a previous state. No more, no less.

In the left column we’re numbering the measurement intervals as they pass by in clock time. In the right column we’re keeping track of brain states as they flip by. Notice that one brain state, 7J63Ω∂, repeats, occurring first at clock interval 26,104,638 and then later at clock interval 26,172,988. What do we make of that? Only that the brain has somehow returned to a previous state. No more, no less.

There’s nothing mysterious about this. Physical systems do it all the time. The earth, for example, moves around the sun, and repeats that motion year after year after year. Clocks do the same thing. At the heart of every clock is some mechanism that goes back and forth, tick tock, at the same rate for as long as the clock has energy. The rest of the clock mechanism simply accumulates the ticks and tocks into the seconds and minutes and so forth that form the pace of our lives. Substituting an electronic pulse for a physical pendulum doesn’t change the basic operating principle.

Now, what happens if the brain repeats, not a single state, but a whole sequence of states? But isn’t that what, for example, the earth does? It repeats a year-long sequence of states, time after time.

What, however, if the sequence of states had a complicated internal structure, like a musical composition? Let us further imagine that you fully absorbed by a performance of that composition so that the music fully specifies your brain state. That implies two things: 1) If you had become absorbed by that music on two different days, then those two moments of absorption are phenomenologically one and the same moments. You have looped in time. 2) If that piece of music was written by Beethoven, and you are not Beethoven, for the duration of your absorption there is no effective difference between you and Beethoven. Phenomenologically, you are all the same individual. You are participating in the same trajectory of mental states. You and Beethoven, but also Wayne and Phyllis Booth. All of you one and the same in the music. And in the same time-loop as well.

You, however, are a modern person, and so you wear one of those clock-time amulets and you live your life to according a calendar. You know that you listened to that Beethoven quartet once on March 31st and then again on June 3rd. No matter how absorbed you were in the music on those occasions, you know it was two occasions.

* * * * *

What I am suggesting, obviously, is that you set aside your amulet and calendar and consider the phenomenon itself. I ask you to consider the possibility that you actually did travel back in time to Wayne and Phyllis Both and, with them, to Beethoven. And I am asking you to do so in the name of physics – of all things.

It is easy enough to think of clock time as an empty frame in which events happen, one after the other. This frame is somehow outside the universe, and so are we when we have recourse to it. Alas, physics took that fiction from us early in the 20th century, relativity in one way, quantum mechanics in another. There is no “outside the universe” and no abstract time. There is only real time, which we measure with real devices.

Those brain states are every bit as real as the tick-tocks in the clock we use to measure them. If your experience in those states is that you are fusing with Beethoven, Wayne, and Phyllis, then that experience commands the same authority as the calendar that says Beethoven was way back then while you, Wayne, and Phyllis are now. Sometimes we attend to the clock and the calendar, and sometimes we give ourselves over to the music, and the dance. Our ability to move back and forth between clock time and brain-state time makes us time travelers.

All of us.

* * * * *

Let us turn the crank on this thought experiment another step. Imagine an idealized group of, say, 35 people. Every so often they get together to sing and dance together, all of them, children adults and infants. Each time they sing the same songs, dance the same steps. Between those sessions each goes about his or her business, in twos and threes, and sixes and, yes, alone as well.

Could we not say that the life of this group loops through time such that, when they’re singing and dancing together, it’s always the same time, the same region in temporal space if you will? Can we think of that moment as a psycho-cultural home base?

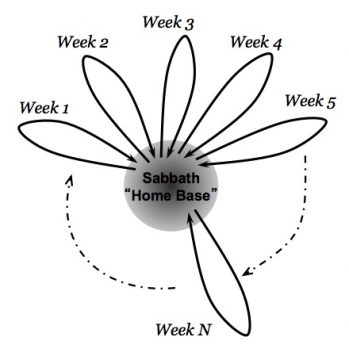

And is that not how religions often operate? Christians celebrate once a week on Sunday; Jews celebrate once a week on Saturday. Not everyone attends regularly, and some attend services on other days as well. Still, to a first approximation one might visualize a congregation’s psychic life like the diagram at the right.  We can think of the plane in general as representing the group’s psychic space. The central region, the Sabbath, is the group’s psycho-cultural home base. Just as the young infant regards her mother as home base and lives her young life moving away from and returning home to mother, so I am suggesting that we can conceptualize a group’s psychic life in the same way.

We can think of the plane in general as representing the group’s psychic space. The central region, the Sabbath, is the group’s psycho-cultural home base. Just as the young infant regards her mother as home base and lives her young life moving away from and returning home to mother, so I am suggesting that we can conceptualize a group’s psychic life in the same way.

Consider the case of Christmas music in the United States and, I assume, at least some of the other countries where Christmas is the occasion for major social activity of various kinds. I am thinking in particular about the way Christmas music runs together in my mind’s ear. All of those songs, traditional carols (e.g. “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen”), popular songs about Christmas, (.e.g. “White Christmas”), and particular pieces of classical music (e.g. the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah) run together like threads in a ball of yarn; you pull one, and all of them come out together, one after the other in no particular order. That’s an annual cycle. Beyond, that there is quadrennial presidential election cycle in the United States which, to a Martian anthropologist, would appear to be a species of religious ritual. It’s not merely that these events occur at regular intervals as marked on the linear time of a calendar, but that certain events always occur at those intervals so that those cycles become “written” into our nervous system and the closely related endocrine systems, which are also coupled to seasonal variation in length of days and types of weather.

If those neural states constitute our psychic being, then that being would seem to be cyclic on various time scales, from the seconds-long scale that defines musical structure up through weekly cycles defined by work and worship, to annual and even longer cyclers, variously defined by typical society-wide events and practices. One might say that, well, sure, but that’s just a metaphor. A metaphor, yes, but not just a metaphor.

Given the prior discussion of brain states, I suggest that we are dealing with something that is both physically real, in terms of the nervous systems of members in the group, and psycho-culturally real, for it is in these central psycho-cultural spaces that basic values are re-affirmed and bonds between group members are strengthened. We have only just begun to understand these phenomena in fully contemporary physical and scientific terms. We have only just begun to appreciate the fact that we have been traveling in time since those moments years and years ago when a group of very clever apes transformed themselves into incipient human beings.

For further reading: I’ve discussed music and time in these terms in Beethoven’s Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture (Basic 2001). The Bernstein anecdote is from Helen Epstein, Music Talks: Conversations with Musicians (McGraw Hill 1987), p. 52). I discuss the amulets more fully in “The Magic of the Bell: How Networks of Social Actors Create Cultural Beings”, Working Paper, 2015, https://www.academia.edu/11767211/The_Magic_of_the_Bell_How_Networks_of_Social_Actors_Create_Cultural_Beings.