Kelly Grovier in BBC News:

Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading).

Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading).

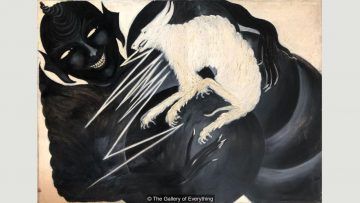

Over the course of the ensuing century, Spiritualism blossomed into a formidable force that shaped countless milestones of cultural expression: from the ‘automatic writings’ of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats to the so-called ‘New Music’ of the avant-garde US-Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg. In the visual arts, the spiritualist dimensions of certain painters is well established. Piet Mondrian once confessed that he “got everything” from the occultist writings of Madame Helena Blavatsky, founder of the mystical Theosophical Society, and Wassily Kandinsky published the seminal aesthetic treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1911.

More here.