Wlliam Dalrymple at The Guardian:

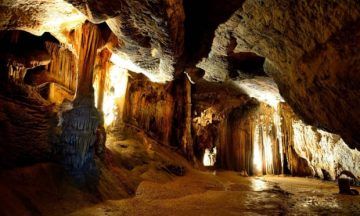

Stories of human journeys into the Underworld are as old as literature itself. But few of them are happy tales. Old Babylonian cuneiform tablets recording the Epic of Gilgamesh were first incised around 1800BC. These tell of the Sumerian hero Enkidu who reappeared from a long imprisonment underground in the Netherworld, during which he had to sail through storms of hailstones that struck him like “hammers”, and surfed waves that attacked his boat like “butting turtles”. Gilgamesh questions him: “Did you see my little stillborn children who never knew existence?” “I saw them,” answers Enkidu.

Stories of human journeys into the Underworld are as old as literature itself. But few of them are happy tales. Old Babylonian cuneiform tablets recording the Epic of Gilgamesh were first incised around 1800BC. These tell of the Sumerian hero Enkidu who reappeared from a long imprisonment underground in the Netherworld, during which he had to sail through storms of hailstones that struck him like “hammers”, and surfed waves that attacked his boat like “butting turtles”. Gilgamesh questions him: “Did you see my little stillborn children who never knew existence?” “I saw them,” answers Enkidu.

Similar journeys end as darkly for Orpheus, Hercules and Aeneas as they do for their direct counterparts in Finnish, Inuit, Aztec, Mayan and Hindu mythology. In Greek mythology tales of haunting journeys down the rivers of the dead are sufficiently common that they have their own collective noun: katabasis. But for every Theseus who enters the labyrinthine darkness of the Underland to triumph against the Minotaur there are many more Eurydices who never return. Such fears, Robert Macfarlane points out, are embedded deep in our language where “height is celebrated but depth is despised. To be ‘uplifted’ is preferable to being ‘depressed’ or ‘pulled down’.”

more here.