James Waddell in MIL:

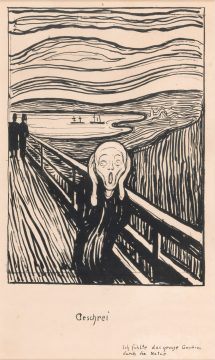

At the start of the 20th century Sigmund Freud observed the psychological phenomenon of “repetition compulsion”, the pathological desire to repeat a pattern of behaviour over and over again. He no doubt would have diagnosed the painter Edvard Munch with such an affliction. As the British Museum’s new exhibition of his work demonstrates, Munch returned obsessively to certain visual motifs: uncanny sunsets, zombie-like faces, threateningly sexualised female bodies.

At the start of the 20th century Sigmund Freud observed the psychological phenomenon of “repetition compulsion”, the pathological desire to repeat a pattern of behaviour over and over again. He no doubt would have diagnosed the painter Edvard Munch with such an affliction. As the British Museum’s new exhibition of his work demonstrates, Munch returned obsessively to certain visual motifs: uncanny sunsets, zombie-like faces, threateningly sexualised female bodies.

Freud might have looked to Munch’s biography for the roots of his mental anguish. There is much to unpick. His mother died from tuberculosis in 1868 when he was five. Nine years later, his sister died of the same disease. At a time of rapid industrialisation and grinding urban poverty, tuberculosis was tragically common. Munch had to watch as his father, a doctor, desperately tried to save the lives of consumptive patients, often resorting to prayer when all else had failed. This, and the Lutheran strictures of Munch’s adolescence in conservative Kristiana (now Oslo), did little to encourage the healthy processing of Munch’s trauma. By the time he reached adulthood he longed to escape, and managed to do so by falling in with a bohemian set of radical artists and writers, including Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg. He soon developed a visual style that cast aside the Scandinavian traditions of formal portraiture and stately landscapes, resulting in vivid and unnerving prints.

Printmaking is by its very nature a process of repetition. There is also something almost violent about its technical vocabulary of acid bites, drypoint scratches and woodcut gouges. Possibly this appealed to Munch, as he printed, scraped, clawed and re-printed, the resulting image darkening with each new impression.

More here.