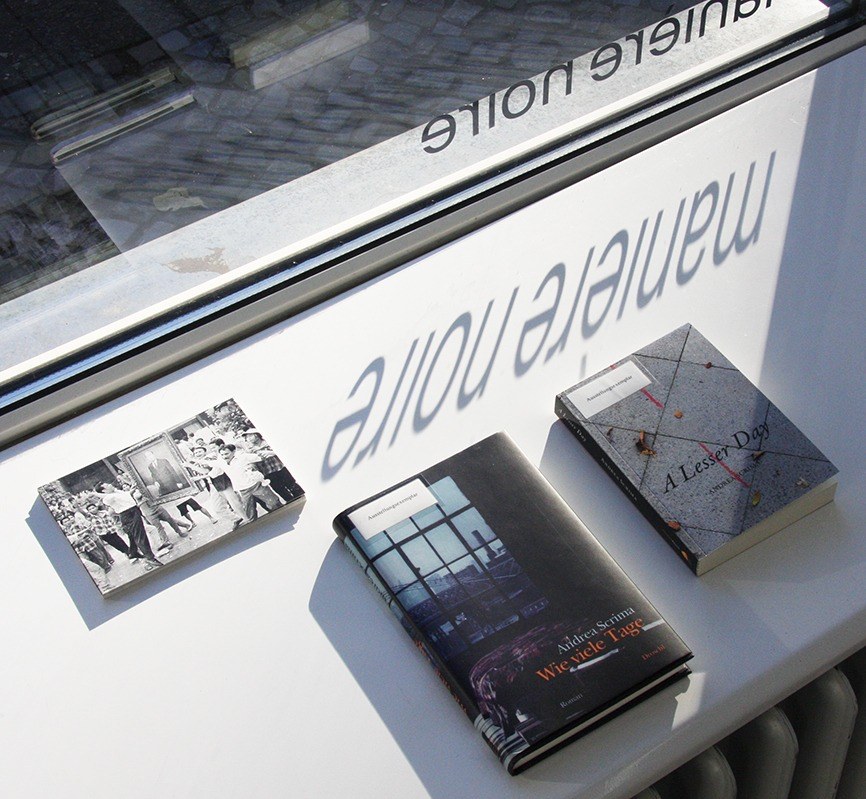

Andrea Scrima’s “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire” at Manière Noire consists of a two-part, large-scale text installation, a small sculpture, and a news photo printed on the invitation card. These three elements interlock in an intricate manner, while the exhibition stands in relation to the novel A Lesser Day, which has recently come out in German translation [Wie viele Tage, Literaturverlag Droschl, 2018]. I spoke to the artist and author about the connections between literature and art, image and reproduction, description of image and text turned into space—in other words, about the multimodal signification processes of this complex work. The following conversation took place via email over a period of several weeks for the most part in August and September, 2018. –Myriam Naumann

Myriam Naumann: “Kent Avenue; how I hadn’t done anything I’d set out to do in New York, how I’d called off the exhibition and worked on the book instead…” In A Lesser Day, processes of emergence and coalescing, for instance of perception or materiality, are always present. At one point, the actual writing of a book becomes the subject matter of the text. How did A Lesser Day and its German translation come about?

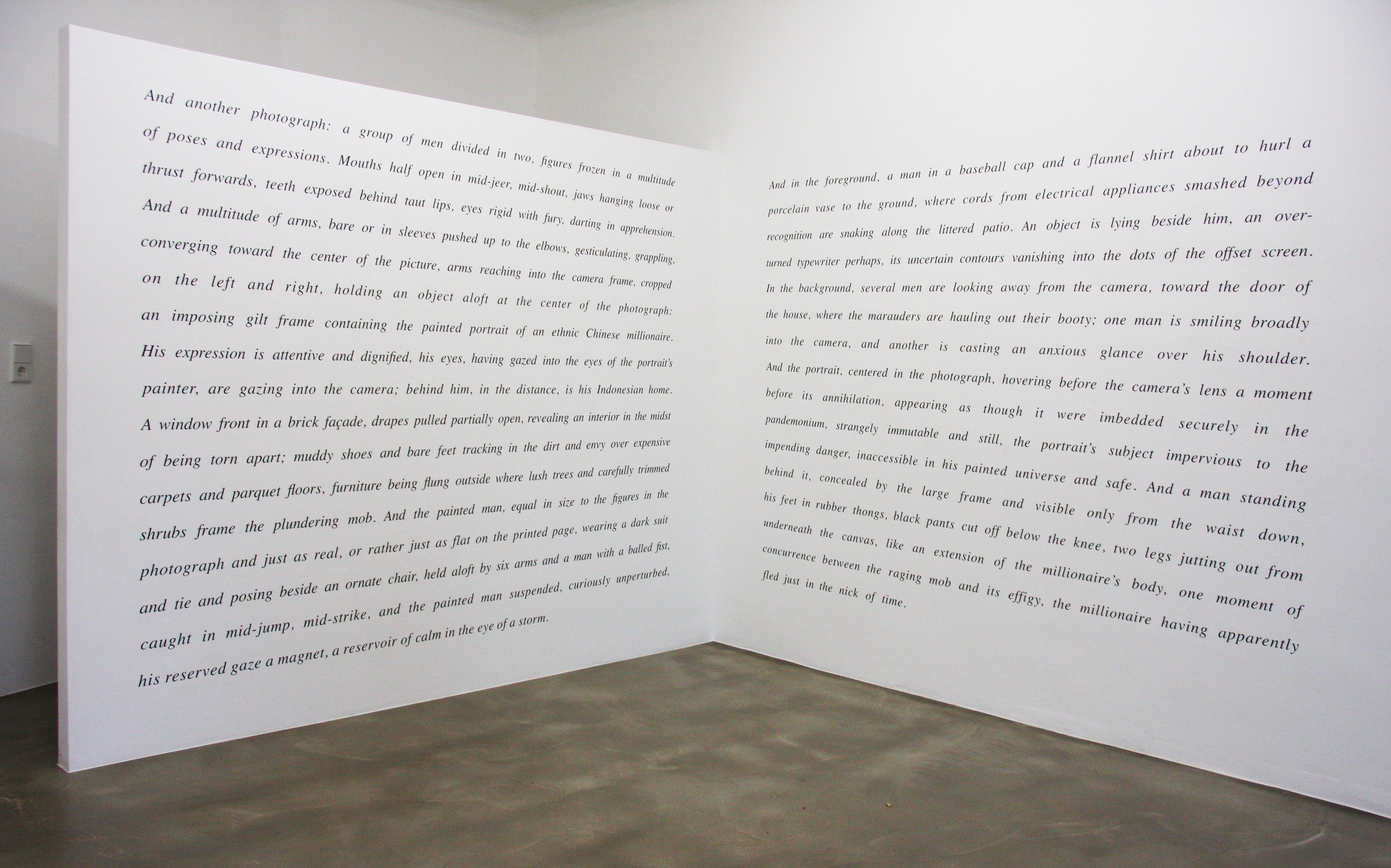

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

These are all formal considerations; at some point I became more interested in the content, the writing itself. The inevitable question that arose was whether these texts could hold their weight in a literary context. And so, in a kind of organic development, my writing grew out of my artistic work; nonetheless, I suddenly saw myself confronted with a complete change of profession. During this time, in September 1999, I received a substantial artist’s grant from the Berlin Senate and used the money to move back to New York and rent a loft on the East River. I blew off the exhibition I was supposed to put up in connection with the grant; I blew off a show at my New York gallery at the time. All I wanted to do was write. It was a very focused period, I wrote hundreds of pages, but the novel I was working on at that time, the book that’s indirectly mentioned in A Lesser Day, was never finished. I’ve promised my Austrian publisher that I’ll deliver the manuscript by next summer, so we’ll see. In any case, A Lesser Day came later, after I’d already returned to Berlin. Without realizing that I was about to embark on a new book, I sat down at my desk one evening and wrote down the first few pages, just like that. The German edition was published several years after the English edition; the translation was a collaboration, a very absorbing one, because I have a fairly precise idea of how my writing should sound in German.

M.N.: Your description of the text installations suggests that the space was inconceivable without text and the text inconceivable without the space. On the other hand, writing a book entails a different type of concentration on subject matter, which in A Lesser Day includes existing and imaginary places, spaces, interstices. Even before the idea of writing a book presents itself, you’re immersed in a kind of “unsuspecting beginning”: you “wrote down the first pages, just like that.” The site for this act is the desk, a recurrent motif in A Lesser Day: “how precarious the order on the desk suddenly seemed;” “the reduction of everything to the daily essentials: a bed, a desk, a sink, a gas stove, a refrigerator.” The book’s narrator lays her trembling hands on the desk; sits at her desk and observes the hostile environment outside; waits at an unnamed person’s desk and hurls a bottle of wine at a wall. The desk is more than just a piece of furniture—what significance does it have for you and for the narrator of A Lesser Day?

A.S.: When I consider these examples, I think of a place where something fundamental takes place, a kind of subconscious. A person seated at a desk is usually alone. The desk is a place to think and to write. In A Lesser Day, it’s also a place where the narrator is constantly cutting photographs out of newspapers: the site of her contemplative, affected, uneasy encounter with the world.

M.N.: Each section of A Lesser Day begins with the name of one of five locations in Berlin and New York: “Eisenbahnstrasse,” “Fidicinstrasse,” “Bedford Avenue,” “Ninth Street,” “Kent Avenue.” The two cities are also described spatially, while the narrator navigates between real and imaginary places. What importance do locations hold for you? How is space to be understood?

A.S.: In A Lesser Day, there are rooms the narrator lives or works in, rooms she remembers, and rooms that she merely imagines. A key question here is how we “inscribe” ourselves into places, whether a part of us remains behind after we’ve left.

M.N.: In the book, there is a funny, very concrete scene for this sort of “inscription.” It takes place at Kent Avenue. There’s a spot on the floor where the paint hasn’t completely dried through, an inadvertent record of the narrator’s footprint as she ponders the color’s relative pinkness. A “wrinkly scar,” a “filigree pattern” is what remains, and a fine skein of dirt settles into it each time the floor is mopped. Does the trace require a material enactment of this kind, or does the latter reveal in an exemplary way how fine the line really is between materiality and immateriality, a person’s presence or absence in a space?

A.S.: The “wrinkly scar” is the small, barely noticeable trace of a fleeting moment. The idea of turning a small wrinkled spot on the painted hallway floor into a memorial for a random conversation already points in the direction of immateriality (if not absurdity), and yet the trace is there; it stands for something. There are also, however, invisible traces. In A Lesser Day, there’s a section in which the narrator goes in search of a place that no longer exists: the building in the South Bronx where her mother grew up. The building has long since been torn down and remains as nothing more than a gap in a numerical sequence, yet nonetheless, somewhere in the air between two buildings erected at a much later date, lies an intersection of coordinates in the very spot where the mother went to bed each night, where she laid her head on her pillow, all throughout her childhood.

M.N.: I’d like to return to the text installation for a moment. In the exhibition “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire” at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire, the method of turning text into space described above undergoes a variation; the result is a complex connection between literature (A Lesser Day) and art (the three works of the exhibition). How would you characterize the relationship between your book and the exhibition?

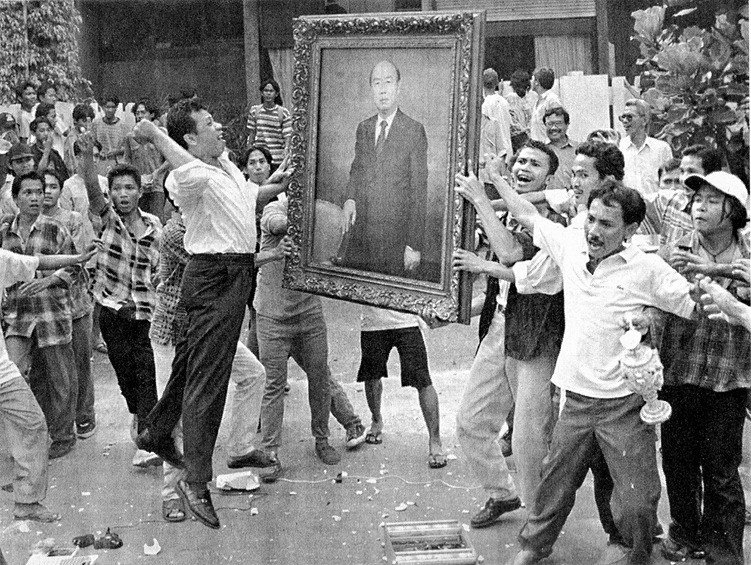

A.S.: The exhibition consists of an image printed on an invitation card; a large-scale text installation on two walls; and opposite these, on a shelf mounted to the wall, a small sculptural object. Although I’ve exhibited many such text works in the past, now, after I’ve published a book, the relationship to text suddenly takes on a new, perhaps even problematic dimension, because the passage I’ve used comes directly out of A Lesser Day. And so it’s no longer about formal questions alone; there’s a reciprocal inquiry between art and literature going on here. Is this nothing more than two vastly enlarged pages of an open book? An image is described: a photograph cut out of the newspaper in which a raging crowd is in the act of plundering a millionaire’s home. In the foreground, an oil painting is held aloft by several people: it’s the portrait of the millionaire. The photo was taken in the 1990s, when ethnic Chinese businessmen living in Indonesia were rumored to have caused the economic crisis of the time and suddenly found themselves in danger. The narrator describes the photograph in painstaking detail; she literally reconstructs the photograph in words. What is the mental image that results from this description, and what relationship does it bear to the original photograph? It’s about the description of an image of an image here: a text about the printed photograph of a portrait painted on canvas of a man who has fled for his life only moments before—an oil painting that was destroyed seconds after the picture was taken. The media-reflexive aspects of this relationship are very interesting to me.

Inserted into this is the sculptural object I mentioned: the empty wrinkled shell of white oil paint left behind after covering an apple half in numerous successive layers of white oil paint as the fruit decays and gradually withers away inside. The art historical references to the still life and to Netherlandish painting are clear enough; they constitute, however, an inversion, because here the oil paint is used not as a means of depicting arrangements of flowers or fruits before they wilt or rot, but implemented in a very concrete sense, to physically conserve something perishable. This object provides an important hint for interpreting the relationship between installation and book.

M.N.: You’re alluding to the “Ontbijtjes,” the table arrangements—still lifes of fruit, desserts, and confection in Flemish painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The fruits were aestheticized in their full magnificence shortly before or during the moment decay set in. While the real fruit, in other words, the “original” has long since disappeared, the painted canvas lasts for centuries. In the case of your object, this principle is both inverted and radicalized: the paint itself becomes the sculptural shell, while inside, particles of decayed matter are mummified. Can you clarify the details of this inversion and explain how the object provides the key for interpreting the relationship between the installation and book? Perhaps you can also take into account that in A Lesser Day, the making of just such an object (in this case an orange and a radish) is converted into literature?

A.S.: The lavish still lifes of the “Ontbijtjes” genre were scenes of vitality, nourishment, and indulgence; at the same time, they bore the first subtle signs of decay, for instance a fly perched on a piece of fruit, or a tiny brown spot. Some of the paintings by Clara Peeters from Antwerp contain miniature self-portraits of the artist in the form of reflections in porcelain or in the burnished tin lids of jugs: a form of ascertaining the self, but also a reference to the fleeting nature of our existence and to death.

My work also contains a reference of this nature; here, however, it’s not about depicting anything, but is a sort of fossil imprint. An inversion takes place: oil paint is used not as a means to portray something realistically, but as material in the fabrication of an actual sculptural object. The difference is subtle, but crucial—because in the framework of the exhibition, this small object offers a possibility for reading the relationship between book and installation. The installation is not a “visualized” book or a mere passage from the novel, but something fundamentally different, something autonomous and stable in itself.

A Lesser Day contains numerous passages that describe artistic processes. Transforming these processes into literature also gives rise to works of art, and while these are immaterial and imagined, they’re no less present. What emerges here is a strange in-between space: are the works described pre-existing works, or are they the product of literary invention? Was the Prepared Object created from its fictional description, or was it the other way around? I’m drawn to this fictional space. For the most part, art and literature are very separate disciplines, and they’re not often perceived in direct relation to one another. There are a few exceptions, for instance the collaboration between Sophie Calle and Paul Auster that began after Auster described some of Calle’s projects in his novel Leviathan. In response, Calle created a facsimile of several book pages that she augmented with handwritten “corrections” in order to clarify the differences between herself and her double, the fictional artist in the book. But it was also, of course, a game, and yet another layer of fictionalization.

In A Lesser Day, the newspaper photo mentioned above is described in words; in the exhibition “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire,” the letters of this description fill two entire walls that together form a corner, transforming the text into an image. And so the viewer can enter into this textual space, take in various passages here and there, become absorbed in his or her own mental images. At the same time, the description is indirectly confronted with its original object: the photograph is printed on the invitation card, small in scale, yet nonetheless a sort of “correction.”

M.N.: In what sense do you see the invitation card as a “correction”?

A.S.: I’m talking about a correction in quotation marks. Actually, it’s more about conflict. We have a parallel image consisting of words that enters into a relationship with the original image, and to an extent superimposes itself upon it. The text isn’t just a description; it also contains observations about the image that aren’t evident or intelligible at first glance. Conversely, the image contains information that resists language. In this way, the “location” of the image becomes unstable and insecure. The text installations that I realized over a longer period of time all in one way or another addressed this unstable location of the image. The majority of these works consisted of a combination of text and photographic image or text and object. One installation I did for the Kunsthaus Dresden, however [how did he smile, how did he blow his nose?, 1999], consists exclusively of text; the writing already addresses a particular image, and any additional visual component would disturb the formal balance. The content of the text is easily summed up: a woman discovers that she’s already in the process of forgetting a man she once loved. She is in possession of a photograph that has the power, or rather had the power of invoking his living image, of conjuring him up in all his uniqueness, his physical presence. To her great distress, however, she discovers that the photograph suddenly yields much less than it once did. She is afraid that she’s already used up the power of the photograph; she decides to look at it as seldom as possible, in the hopes of somehow arresting the process of dissolution. But of course the problem lies in the workings of her own memory. The corresponding inner image that the photograph evokes is in the process of disintegrating; the location of the image retreats beyond her grasp. The installation consists solely of a text that sets out to convey the finite nature of the remembered or imagined image.

M.N.: You described the process by which the text is transformed into an image. The gallery Manière Noire offers several walls for exhibiting work. You deliberately decided to arrange the text blocks into a corner situation as an installation instead of concentrating on a single wall. What was behind this decision?

A.S.: The text is separated into two large walls divided by a space, the corner of the room—a gap that exudes its own strange presence. There are several reasons why the text installation assumes this diptych form. A doubling takes place, coupled with an emphasis on the interstice: the space between the image and the description of the image, photo and text, text image and text content, work of art and book. The notion of an in-between space is also important in thematic terms. The scene described takes place between two highly opposed situations: order and chaos. The photograph itself is divided in two; there are various figures to the left and right, while suspended in the middle is a framed portrait of the missing millionaire. The gestures of the persons described in the text are all caught in an intermediate state; they are, like all photographic images, “frozen in time.” Mouths are “half open in mid-jeer, mid-shout,” a man with a balled fist is caught “mid-jump, mid-strike.” And then there’s the—highly serendipitous—optical extension of the millionaire’s body by another man standing behind the oil painting, “one moment of concurrence between the raging mob and its effigy.” To carry this thought even further, the gaze of the millionaire is located in another in-between space: his eyes, which once gazed into the eyes of the painter, are now gazing into the camera and thus into the eyes of the person viewing the photograph, then the eyes of the person reading the newspaper, and then, at another remove, the eyes of the viewer of the exhibition. We see the painting a second, perhaps half a second before its annihilation. Finally, in the actual exhibition situation, when the viewer stands facing the corner of the room, surrounded by text to the left and right, he or she enters into this textual space and assumes the position of the oil painting, becomes the center of the (text) image, and, by extension, its subject.

M.N.: This interplay of exchanged gazes comes to fore when the viewer assumes this position; at the same time, it brings into focus the multimodal signification processes in your work. Addressing the Indonesian uprising of the 1990s is only one example for the way in which the historical and political are always present in your work, although this presence is never obvious or polemic. How do the historical and political enter into your work, and what importance do they acquire in A Lesser Day and the exhibition?

M.N.: This interplay of exchanged gazes comes to fore when the viewer assumes this position; at the same time, it brings into focus the multimodal signification processes in your work. Addressing the Indonesian uprising of the 1990s is only one example for the way in which the historical and political are always present in your work, although this presence is never obvious or polemic. How do the historical and political enter into your work, and what importance do they acquire in A Lesser Day and the exhibition?

A.S.: The Fall of the Berlin Wall; the long lines of East Germans waiting for their “greeting money,” a one-time bonus of 100 German marks granted to them by the government of the Federal Republic; the weekend the currency union went into effect a half year prior to German Reunification, when Eastern products were replaced with the colorful, far more expensive Western products in most East German shops; the wars in the former Yugoslavia and the slaughter: these and other scenes appear abruptly in the book. Later, just prior to the turn of the millennium, a sense of dread hanging over the World Trade Center is added to the mix, together with the “YK2” mania, the fear that the computerized world was incapable of adjusting to a four-digit change in date and might trigger some sort of apocalypse. The passages are described in a kind of trance; the political appears to take place on the outer fringes of the narrative, as a kind of backdrop. In a book that completely breaks with linearity and chronology, however, these historical interludes assume a very important function: they act as coordinates that anchor the various scenes in temporal terms. The passages in which the narrator sits at a desk or table and cuts pictures out of the newspaper constitute a leitmotif. But she never explains why she does this. It seems to be a part of her art. In any case, some of the images are of people carrying images of people in their hands. Again and again, the narrator mentions the flatness of the printed photographs—that the eye cannot differentiate between the people depicted and the reproduced image-within-an-image: a reference to the immateriality and, in the final analysis, unreliability of the images, particularly news images—as well as the unreliability of news reporting in general.

M.N.: One possibility would have been to print the news photos described in A Lesser Day in the actual book—as a documentation, illustration, or image-based (as opposed to text-based) visualization. As you’ve explained, this was not an option. Do the absence of images and their transformation into a literary description imply a form of cultural criticism?

A.S.: Cultural criticism was not the main thing I had in mind. We’re flooded with photographic imagery; you could say that the image is in crisis, because the inundation and digital manipulability lessen the effect individual images exert on us. We’ve become insatiable; we need a constant supply. On top of this, there’s a new mistrust, a new skepticism. And so of course you could read the descriptions of images in A Lesser Day as a criticism, as a return to the word, to a reliability and precision that can no longer automatically be expected from images. But for me it’s about something altogether different. I’m simply interested in the mental images that arise in the reader’s imagination: what kind of images are they? Or is it more a series of sequential, fragmented images, because language reveals itself through a linear process and not, as with the photographic image, as a whole?

A.S.: Cultural criticism was not the main thing I had in mind. We’re flooded with photographic imagery; you could say that the image is in crisis, because the inundation and digital manipulability lessen the effect individual images exert on us. We’ve become insatiable; we need a constant supply. On top of this, there’s a new mistrust, a new skepticism. And so of course you could read the descriptions of images in A Lesser Day as a criticism, as a return to the word, to a reliability and precision that can no longer automatically be expected from images. But for me it’s about something altogether different. I’m simply interested in the mental images that arise in the reader’s imagination: what kind of images are they? Or is it more a series of sequential, fragmented images, because language reveals itself through a linear process and not, as with the photographic image, as a whole?

M.N.: I’d like to talk about two positings in A Lesser Day, the title and the opening quote. A Lesser Day and Wie viele Tage both place the temporal unit of “day/Tag” in a prominent position in the text—immediately visible to all at the very beginning—and at the same time infuse the title with an indeterminate quality. There’s a passage in the German edition that contextualizes the title; at the same time, through a subtlety of meaning, it pulls away from this connection: “How many days spent immobile, waiting for these twirling bits of thought to slowly settle down at the bottom of the jar, afraid to move…” Does the title lead the reader into the book’s program and methodology, while offering comparatively little (as is so often the case) in terms of the book’s themes? Moreover: for the exhibition “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire,” you decided on a title that bears no obvious reference to the book. What was behind this choice?

A.S.: The title of the English edition, A Lesser Day, comes from a passage in the book in which the narrator describes a photo project she’s working on in which she takes one photograph each day for the duration of a year, using a cheap instamatic camera. It’s very important that each day be represented by a photograph. The majority of the images are the product of a perception honed by the painting process: patterns of erosion on a wall, the way the light falls on the pavement, etc. But there are also days when she waits too long to press the shutter release, although she knows that there’s too little light to expose the film; that no visible image will result. These are the “lesser days,” the days on which she has seen something, and thought something, but that have left behind no concrete proof apart from the greenish or brownish monochromatic blurs that she has to pay a considerable amount of money to have developed by hand, because the machines in the photo lab automatically skip over what would normally be regarded as worthless. The developing machines are calibrated this way; nothing can be done about it. But she insists on the fact that the “lesser days” are just as important.

In addition, the phrase “a lesser day” occurs in the same passage of the book in which another image is described: a winding snake of spilled paint on a sidewalk whose granite paving stones were removed at some point and then reassembled, but in another order, so that the winding line is no longer one continuous flow, but an interrupted course that goes first in one, then in another direction: a metaphor for memory’s imperfect reconstruction of time and experience, the way in which we perceive, and rewrite, our lives in retrospect. These two metaphors are thematically intertwined.

As we worked on the German edition, we discovered that the book title was impossible to translate; this is why we had to resort to another passage of the book. The German title Wie viele Tage [How many days] suggests the temporal order that’s so central here, but the emphasis is shifted to the thought process, or rather, the process of being able to think at all, or not being able to think.

The fact that exhibition title and book title are not the same has a very simple reason. The exhibition text comprises one and a half, two pages of a 190-page book. The installation is neither a visualization of the book nor a reading sample, but an autonomous work that operates according to its own inner logic. As I’ve explained, it’s about the relationship between the description of a photo and the photo itself. But this relationship points to another layer, that of reproduction. The distance to the original is composed of several degrees of remove. In optical terms, the digitized image of a scanned black-and-white screened and printed photograph doesn’t differentiate between actual living people and human images in reproduction, in this case, the oil painting. On the printed page of a newspaper, everything becomes equally flat: the face of the painted millionaire, the faces of the people actually occupying the physical space around him. In the reproduction, they merge together, become suspended in a different shared space. It’s the lexical description of the picture alone that separates these planes and reinstates the distinction between image and reproduction.

M.N.: You placed a quote from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets at the beginning of your book “. . . see, now they vanish, The faces and places, / with the self which, as it could, loved them, / To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern.” What made you choose these lines, and what connection exists between A Lesser Day and the poem?

A.S.: The quote contains the connection. Eliot speaks of a new pattern that arises when, in retrospect, one creates meaning out of the patterns of the forgotten and disappeared. Memory is always a process of reordering, rewriting. The “other pattern” that Eliot speaks of is the “transfiguration” of the past, in other words art, literature, and poetry.

M.N.: Forgetting and disappearing, remembering and reconstructing the past are processes in A Lesser Day that envelop and entangle the narrator. Scenes of transience and death are the signs of time that lend these processes force: the death of family members, of neighbors, of animals, together with the realization of one’s own mortality. Is the self reassuring itself here, along with the “reordering” of life mentioned above? And what, to your mind, is the relationship between death and memory?

A.S.: The memories conjured up in A Lesser Day commence with the father’s death. The narrator perceives strange alterations in the way her memory works, her sense of time, even her own corporeality. In her grief, she experiences time as something malleable and mutable; the loss has left an imprint on her perception so deep that she experiences the present moment as though she were looking back to the distant past from an indeterminate point in the future. It’s less about the self reassuring itself here than about it breaking apart, dissolving. Everything stands under the sign of death; she experiences even the killing of insects—and the book is full of insects, all of whom have a strong will to live—as a massacre.

M.N.: The idea of the “pattern” can also be taken as a clue for how to read A Lesser Day, because your book sensitizes the reader to the “pattern” as a phenomenon in the world. Would you agree that the “pattern” constitutes a phenomenon? And what “patterns” unfold for you in A Lesser Day?

A.S.: There are mathematical patterns that exist objectively in nature, and there are the patterns that derive from human perception. The latter can be either empirically observed structures, projected orders on the randomness of the world, or signs steeped in personal meaning. There’s a passage in A Lesser Day in which this last variation appears. A chance intersection of nondescript “events” is described in detail: a coffee cup thrown from a passing truck; a thin trickle of dog urine; a slip of paper that someone has scribbled something on. For the narrator, the concatenation of these three events takes on a strange importance, as though something lay imbedded within it, written just for her, something she is unable to read. The slip of paper actually turns up once again at a later point in the book: many years later, the narrator finds it somewhere among her old papers, and again it presents itself as a complete mystery to her.

M.N.: Along with psychological patterns, we see linguistic patterns that not only describe the world, but also conjure it into being. In A Lesser Day, the leitmotif “but that came later” occurs twenty-three times as a stylistic pattern of repetition and allusion, creating a temporal connection between the past, the present, and the future. What made the phrase “but that came later” so interesting for you while writing the book?

A.S.: I wanted to make it clear that chronology, if it exists at all, is highly unreliable. The narrating self tries to remember; as she relates certain events and her inner perception of things that have happened, she grows increasingly confused. Again and again, she’s forced to correct herself. We don’t, of course, remember in a linear sequence, but in a very odd manner and by way of detour; we remember the things that left the strongest emotional impression on us. To create a temporal order from this means, first, to collect the fragments and then, later, to bring them into some kind of form so that it makes sense as a whole. We compose and invent when we remember; we create new constellations, new meanings.

M.N.: We could conclude with a number of themes, ranging from the literary form of the novel and the question of autofiction to that of reception. I’d like to talk about this last point. Your book has been reviewed—and celebrated—widely, both in the cultural sections of renowned papers and on national radio. This is heartening to see, and I’m sure it’s an important affirmation for your work. There were also many comments in response to the exhibition, i.e. in conversations with visitors to the gallery. What are your thoughts on the viewers’ perception, and how do you assess these reactions to your work? Do you relinquish control over how your works are interpreted?

M.N.: We could conclude with a number of themes, ranging from the literary form of the novel and the question of autofiction to that of reception. I’d like to talk about this last point. Your book has been reviewed—and celebrated—widely, both in the cultural sections of renowned papers and on national radio. This is heartening to see, and I’m sure it’s an important affirmation for your work. There were also many comments in response to the exhibition, i.e. in conversations with visitors to the gallery. What are your thoughts on the viewers’ perception, and how do you assess these reactions to your work? Do you relinquish control over how your works are interpreted?

A.S.: My work is done the moment I’ve finished writing the book or setting up the exhibition. And yet: readers and visitors to the gallery like to have certain things explained to them. We had an artist’s conversation to accompany the exhibition, and the response was one of attentive interest and concentration. And so it made sense to discuss, in a live situation, the themes we’ve been illuminating in detail here, in our written conversation. I’ve held a lot of readings this year, and I selected different sections from the book each time so that I wouldn’t always be talking about the same thing; in this way, they stayed interesting for me, as did the questions people posed. But when the FAZ offered me a full page for my essay on patriotism [“The Problem with Patriotism: A Critical Look at Collective Identity in the U.S. and Germany,” The Millions, 7/3/2018; in German: “Wie ich Amerika verlor,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 8/19/2018], the deluge of letters to the editor surprised and finally alarmed me. After 95 readers’ comments arrived within the first few hours of publication, they deactivated the comment function for the online edition. I never suspected the degree of arrogance, sarcasm, and attention-mongering lurking in the FAZ readership, let alone the appalling degree of sympathy for the right-wing AfD, which is apparently becoming more and more acceptable in polite society. Some of the comments sounded as though they weren’t aimed at my essay, but a different essay altogether, one situated in their own heads. If my work is wrongly interpreted, there’s very little I can or wish to do to counter that. My readers, my public will find me in any case.

“The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire,” an exhibition by the artist and author Andrea Scrima in the Galerie Manière Noire, Berlin

September 8 – October 19, 2018

Curated by Majla Zeneli.

To read the full installation text, right-click on the image to open it in another tab.

Myriam Naumann is a research associate in cultural studies at the Institut für Kulturwissenschaft, Humboldt-Universität Berlin.