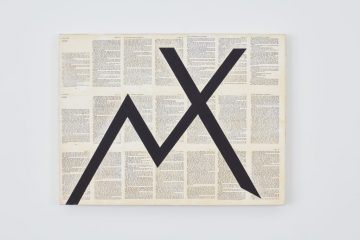

Angel Abreu at The Paris Review:

In 1986, at the age of twelve, I joined Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival. I first met Tim as a seventh grader at the Intermediate School 52 where he was teaching at the time. Tim had only intended to stay at the school for a few weeks. The students had made charcoal drawings on the ceiling of the classroom, and the walls were covered in graffiti. Tim often described the art room as the “Hip-Hop Sistine Chapel.” He was convinced that there was a profound reason he was there.

In 1986, at the age of twelve, I joined Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival. I first met Tim as a seventh grader at the Intermediate School 52 where he was teaching at the time. Tim had only intended to stay at the school for a few weeks. The students had made charcoal drawings on the ceiling of the classroom, and the walls were covered in graffiti. Tim often described the art room as the “Hip-Hop Sistine Chapel.” He was convinced that there was a profound reason he was there.

Timothy William Rollins was born in 1955 in a small town in central Maine. Similar to the South Bronx, Pittsfield was economically downtrodden and its youth struggled against the pitfalls of low expectations. Tim was extremely motivated and precocious. He was a gifted artist, an avid reader, and an amateur scholar of Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King’s writings and speeches, combined with Tim’s Sunday school teaching, would form the basis of his pedagogical philosophy with K.O.S. Tim earned his BFA from SVA in 1977 and after graduate studies at New York University, in art education and philosophy, he began teaching in the New York City public school system. In 1982, Tim stepped off the 2 train at Prospect Ave in the South Bronx for the first time.

more here.

“Technology will surely drown us. The individual is disappearing rapidly. We’ll eventually be nothing but numbered ants. The group thing grows.” So said

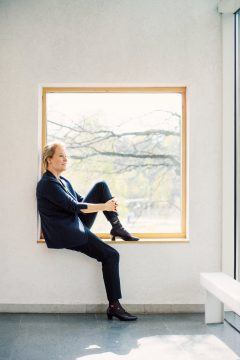

“Technology will surely drown us. The individual is disappearing rapidly. We’ll eventually be nothing but numbered ants. The group thing grows.” So said  Dr. Arnold won fame and the Nobel Prize for developing a technique called directed evolution, a way of generating a host of novel enzymes and other biomolecules that can be put to any number of uses — detoxifying a chemical spill, or example, or disrupting the mating dance of an agricultural pest. Or removing laundry stains in eco-friendly cold water, or making drugs without relying on eco-hostile metal catalysts. Rather than seeking to design new proteins rationally, piece by carefully calculated piece — as many protein chemists have tried and mostly failed to do — the Arnold approach lets basic evolutionary algorithms do the work of protein composition and protein upgrades. The recipe is indeed an engineer’s dream: simple. You start with a protein that already has some features you’re interested in, such as stability in high heat or a knack for clipping apart fats. Using a standard lab trick such as polymerase chain reaction, you randomly mutate the gene that encodes the protein. Then you look for slight improvements in the resulting protein — a quickened pace of activity, say, or a vague inclination to carry out a task it wasn’t performing before, or a willingness to operate under conditions it deplored in the past.

Dr. Arnold won fame and the Nobel Prize for developing a technique called directed evolution, a way of generating a host of novel enzymes and other biomolecules that can be put to any number of uses — detoxifying a chemical spill, or example, or disrupting the mating dance of an agricultural pest. Or removing laundry stains in eco-friendly cold water, or making drugs without relying on eco-hostile metal catalysts. Rather than seeking to design new proteins rationally, piece by carefully calculated piece — as many protein chemists have tried and mostly failed to do — the Arnold approach lets basic evolutionary algorithms do the work of protein composition and protein upgrades. The recipe is indeed an engineer’s dream: simple. You start with a protein that already has some features you’re interested in, such as stability in high heat or a knack for clipping apart fats. Using a standard lab trick such as polymerase chain reaction, you randomly mutate the gene that encodes the protein. Then you look for slight improvements in the resulting protein — a quickened pace of activity, say, or a vague inclination to carry out a task it wasn’t performing before, or a willingness to operate under conditions it deplored in the past.

Consider a hypothetical society that severely marginalizes individuals with red hair and considers red hair to be a genetic disorder with a recessive pattern of inheritance. The “pathology” is determined to be an imbalance between the levels of the red pigment pheomelanin and dark pigment eumelanin in the hair filaments. Red-haired individuals—and parents of red-haired children—in this society go to extreme lengths to dye their hair black. In fact, this society has spent extensive resources to develop complex dyeing procedures, performed only by specially trained medical professionals, that work best for red hair and last longer than regular dyes.

Consider a hypothetical society that severely marginalizes individuals with red hair and considers red hair to be a genetic disorder with a recessive pattern of inheritance. The “pathology” is determined to be an imbalance between the levels of the red pigment pheomelanin and dark pigment eumelanin in the hair filaments. Red-haired individuals—and parents of red-haired children—in this society go to extreme lengths to dye their hair black. In fact, this society has spent extensive resources to develop complex dyeing procedures, performed only by specially trained medical professionals, that work best for red hair and last longer than regular dyes. The Great Crash of 2007–2009 stripped American middleclass families of wealth. It gave rise to nativist politics on the right and socialism on the left, killing credence in neoliberal market capitalism in both the United States and Europe. It buried the Washington consensus that had energized bipartisan support for U.S. leadership around the world. Indeed, China has replaced the United States as the leading country whose investment drives the global economy.

The Great Crash of 2007–2009 stripped American middleclass families of wealth. It gave rise to nativist politics on the right and socialism on the left, killing credence in neoliberal market capitalism in both the United States and Europe. It buried the Washington consensus that had energized bipartisan support for U.S. leadership around the world. Indeed, China has replaced the United States as the leading country whose investment drives the global economy. My friend Laurette has two cats, Zhanna and Pixie. When Laurette pets Zhanna, Pixie interferes by attacking Zhanna. By analogy to humans, it is natural to interpret Pixie’s behaviour as jealousy, but perhaps Pixie is just attempting to assert dominance or establish territoriality. There have been no experimental studies of cats to discriminate between jealousy and alternative hypotheses, but

My friend Laurette has two cats, Zhanna and Pixie. When Laurette pets Zhanna, Pixie interferes by attacking Zhanna. By analogy to humans, it is natural to interpret Pixie’s behaviour as jealousy, but perhaps Pixie is just attempting to assert dominance or establish territoriality. There have been no experimental studies of cats to discriminate between jealousy and alternative hypotheses, but  A few weeks ago, a friend of mine, Paul Embery, found himself hit by a Twitter storm. Paul is a trade unionist, a socialist and is emerging as a polemical journalist of some distinction. Like many, but not all who identify as Blue Labour, he argues strongly for the democratic and radical possibilities of Brexit, which he views as a class issue. He found himself engaged in a Twitter spat with Mike Harding, who describes himself on his website as a “singer, songwriter, comedian, author, poet, broadcaster and multi-instrumentalist”, and there is no reason to doubt that he is all those things and more. He views Brexit as a horrible prelude to a new world war. Mike is from Crumpsall in Manchester, Paul is from Dagenham in the borderlands of Essex and east London. It was never going to go well.

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine, Paul Embery, found himself hit by a Twitter storm. Paul is a trade unionist, a socialist and is emerging as a polemical journalist of some distinction. Like many, but not all who identify as Blue Labour, he argues strongly for the democratic and radical possibilities of Brexit, which he views as a class issue. He found himself engaged in a Twitter spat with Mike Harding, who describes himself on his website as a “singer, songwriter, comedian, author, poet, broadcaster and multi-instrumentalist”, and there is no reason to doubt that he is all those things and more. He views Brexit as a horrible prelude to a new world war. Mike is from Crumpsall in Manchester, Paul is from Dagenham in the borderlands of Essex and east London. It was never going to go well. Many people believe that truth conveys power. If some leaders, religions or ideologies misrepresent reality, they will eventually lose to more clearsighted rivals. Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things. On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb.

Many people believe that truth conveys power. If some leaders, religions or ideologies misrepresent reality, they will eventually lose to more clearsighted rivals. Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things. On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb. Over at the Boston Review, Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier have the lead piece in a forum on the issue of information and democracy, with responses by Riana Pfefferkorn, Joseph Nye, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Allison Berke, Jason Healey, and Astra Taylor:

Over at the Boston Review, Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier have the lead piece in a forum on the issue of information and democracy, with responses by Riana Pfefferkorn, Joseph Nye, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Allison Berke, Jason Healey, and Astra Taylor:

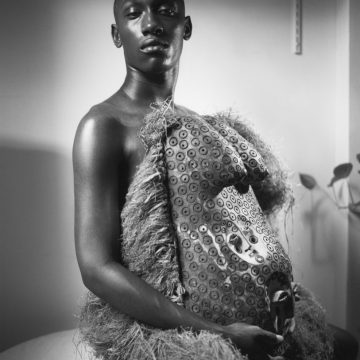

Adam Shatz in The New York Review of Books:

Adam Shatz in The New York Review of Books: Pratap Bhanu Mehta in Indian Express:

Pratap Bhanu Mehta in Indian Express: IN THE SPRING

IN THE SPRING There’s a revealing moment early in “Funny Man,”

There’s a revealing moment early in “Funny Man,”  Conspiracy theorists get a seriously bad press. Gullible, irresponsible, paranoid, stupid. These are some of the politer labels applied to them, usually by establishment figures who aren’t averse to promoting their own conspiracy theories when it suits them. President George W. Bush denounced outrageous conspiracy theories about 9/11 while his own administration was busy promoting the outrageous conspiracy theory that Iraq was behind 9/11.

Conspiracy theorists get a seriously bad press. Gullible, irresponsible, paranoid, stupid. These are some of the politer labels applied to them, usually by establishment figures who aren’t averse to promoting their own conspiracy theories when it suits them. President George W. Bush denounced outrageous conspiracy theories about 9/11 while his own administration was busy promoting the outrageous conspiracy theory that Iraq was behind 9/11. Murray Gell-Mann (

Murray Gell-Mann (