Category: Recommended Reading

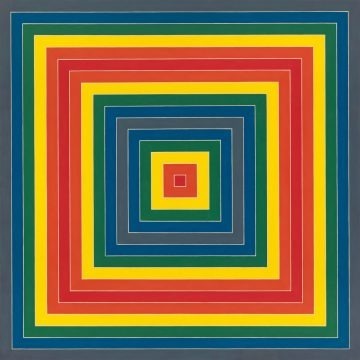

Painting in Color in the 1960s

Karen Wilkin at The New Criterion:

The show’s subtitle, “Painting in Color in the 1960s,” can raise expectations of an emphasis on what Clement Greenberg called “post-painterly abstraction” in 1964, when he organized an exhibition with that title for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; I’ve even heard “Spilling Over” described as “the Color Field show.” (“Post-painterly,” of course, is a nod at the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin’s classification of “painterly” painting—the broad brushwork and softly modeled forms of the Venetian Renaissance, for example, as opposed to Florentine clarity and crisp drawing. Greenberg updated “painterly” to refer to the loose, layered paint application of gestural Abstract Expressionism, which he referred to derisively as “the Tenth Street touch.”) “Post-Painterly Abstraction” surveyed a new generation of painters who challenged Ab Ex’s tonal modulations and heightened emotionalism—synonymous with serious painting for more than a decade—with thin, radiant expanses of clear intense hues. Later termed Color Field painters, the “post-painterly” artists made color the main carrier of meaning in their pictures and substituted a kind of cool detachment for overt drama.

The show’s subtitle, “Painting in Color in the 1960s,” can raise expectations of an emphasis on what Clement Greenberg called “post-painterly abstraction” in 1964, when he organized an exhibition with that title for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; I’ve even heard “Spilling Over” described as “the Color Field show.” (“Post-painterly,” of course, is a nod at the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin’s classification of “painterly” painting—the broad brushwork and softly modeled forms of the Venetian Renaissance, for example, as opposed to Florentine clarity and crisp drawing. Greenberg updated “painterly” to refer to the loose, layered paint application of gestural Abstract Expressionism, which he referred to derisively as “the Tenth Street touch.”) “Post-Painterly Abstraction” surveyed a new generation of painters who challenged Ab Ex’s tonal modulations and heightened emotionalism—synonymous with serious painting for more than a decade—with thin, radiant expanses of clear intense hues. Later termed Color Field painters, the “post-painterly” artists made color the main carrier of meaning in their pictures and substituted a kind of cool detachment for overt drama.

more here.

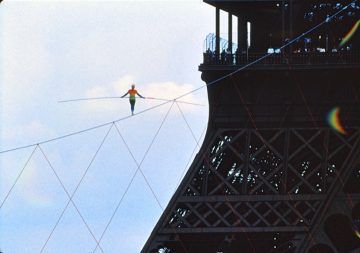

Philippe Petit, Artist of Life

Paul Auster at The Paris Review:

Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing.

Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing.

After living in France for four years, I returned to New York in July 1974. For a long time I had heard nothing about Philippe Petit, but the memory of what had happened in Paris was still fresh, a permanent part of my inner mythology. Then, just one month after my return, Philippe was in the news again—this time in New York, with his now-famous walk between the towers of the World Trade Center. It was good to know that Philippe was still dreaming his dreams, and it made me feel that I had chosen the right moment to come home.

more here.

Coleridge, the Wordsworths and Their Year of Marvels

Nicholas Roe at Literary Review:

Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world.

Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world.

more here.

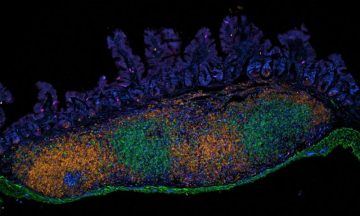

Could boosting the gut microbiome be the secret to healthier older age?

From Phys.Org:

Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human gut microbiome have been linked to increased frailty, inflammation and increased susceptibility to intestinal disorders. These age-dependent changes to the gut microbiome happen in parallel with a decrease in function of the gut immune system but, until now, it was unknown whether the two changes were linked.

Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human gut microbiome have been linked to increased frailty, inflammation and increased susceptibility to intestinal disorders. These age-dependent changes to the gut microbiome happen in parallel with a decrease in function of the gut immune system but, until now, it was unknown whether the two changes were linked.

“Our gut microbiomes are made up of hundreds of different types of bacteria and these are essential to our health, playing a role in our metabolism, brain function and immune response,” explains lead researcher Dr. Marisa Stebegg. “Our immune system is constantly interacting with the bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. As immunologists who study why our immune system doesn’t work as well as we age, we were interested to explore whether the make-up of the gut microbiome might influence the strength of the gut immune response.”

Co-housing young and aged mice (mice naturally like to sample the faecal pellets of other mice!) or more directly performing faecal transfer from young to aged mice boosted the gut immune system in the aged mice, partly correcting the age-related decline. “To our surprise, co-housing rescued the reduced gut immune response in aged mice. Looking at the numbers of the immune cells involved, the aged mice possessed gut immune responses that were almost indistinguishable from those of the younger mice.” commented Dr. Michelle Linterman, group leader in the Immunology programme at the Babraham Institute. The results show that the poor gut immune response is not irreversible and that the response can be strengthened by challenging with appropriate stimuli, essentially turning back the clock on the gut immune system to more closely resemble the situation in a young mouse.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Untitled [Executions have always been public spectacles]

Executions have always been public spectacles. It is New Year’s

2009 in Austin and we are listening to Jaguares on the speakers.

Alexa doesn’t exist yet so we cannot ask her any questions. It is

nearly 3 AM, and we run out of champagne. At Fruitvale Station,

a man on his way home on a train falls onto the platform, hands

cuffed. Witnesses capture the assassination with a grainy video on

a cell phone. I am too drunk, too in love, to react when I hear the

news. I do not have Twitter to search for the truth. Rancière said

looking is not the same as knowing. I watch protests on the

television while I sit motionless in the apartment, long after she

left me. Are we what he calls the emancipated spectator, in which

spectatorship is “not passivity that’s turned into activity” but,

instead, “our normal situation”? Police see their god in their

batons, map stains and welts on the continents of bodies. To beat

a body attempts to own it. And when the body cannot be owned,

it must be extinguished.

by Mónica Teresa Ortiz

from the Academy of American Poets.

Sunday, June 2, 2019

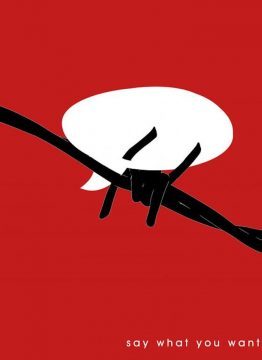

Who has the right to speak?

Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

Historically, the issues were relatively clear. Censorship was imposed from the top. Its aim was to deflect, contain or deem illegitimate any challenge to power.

Today, the issues seem less straightforward. Censorship still exists in the traditional sense of shielding those in power from challenge. Increasingly, however, much censorship today, particularly in liberal democracies, is imposed in the name of protecting not the powerful but the powerless or the vulnerable: laws against hate speech, for instance, or restricting the scope of racists or bigots.

This has created confusion and debate, particularly on the left. Where once the left was clearly opposed to censorship, now many support restrictions in the name of the progressive good. As the left has vacated the ground of free speech, the right, and the far-right, have become encamped upon it. Their attachment to freedom of expression is illusory and hypocritical. But this has further distorted the debate because the cause of free speech has come to be seen as the property of the right and the far-right, and made many liberals, and many on the left, even more hostile to the idea of free speech.

What I want to do today is to address some of these issues.

More here.

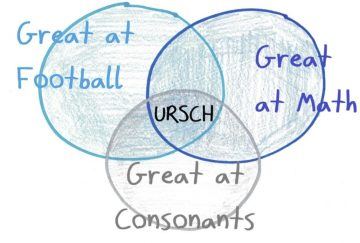

Why Teachers Should Read John Urschel’s Book

Ben Orlin in Math With Bad Drawings:

Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive.

Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive.

PhD in applied math at MIT? Also impressive.

Four consecutive consonants in your surname? Very impressive.

Perhaps none of these achievements, in isolation, is enough to confer celebrity. But look to the center of this peculiar Venn diagram, and you will find only a single name inscribed: John Urschel.

Urschel’s new memoir—Mind and Matter: A Life in Math and Football, cowritten with his partner Louisa Thomas—is a good classroom book, a multipurpose tool. His NFL background makes him a role model for the reluctant. His logic puzzles are brain food for the math-hungry. And his dual career is a conversation starter for everyone else.

More here.

How Britain stole $45 trillion from India

Jason Hickel in Al Jazeera:

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of India – as horrible as it may have been – was not of any major economic benefit to Britain itself. If anything, the administration of India was a cost to Britain. So the fact that the empire was sustained for so long – the story goes – was a gesture of Britain’s benevolence.

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of India – as horrible as it may have been – was not of any major economic benefit to Britain itself. If anything, the administration of India was a cost to Britain. So the fact that the empire was sustained for so long – the story goes – was a gesture of Britain’s benevolence.

New research by the renowned economist Utsa Patnaik – just published by Columbia University Press – deals a crushing blow to this narrative. Drawing on nearly two centuries of detailed data on tax and trade, Patnaik calculated that Britain drained a total of nearly $45 trillion from India during the period 1765 to 1938.

It’s a staggering sum. For perspective, $45 trillion is 17 times more than the total annual gross domestic product of the United Kingdom today.

How did this come about?

More here.

Who really owns the past?

Michael Press in Aeon:

Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

What is most striking about this campaign is its seeming indifference to the lives of the people who call the city home. UNESCO’s promotional video pans through the old city; block after block after block lies completely devastated … only for the camera to abandon them for the one monument that will actually be rebuilt. What kind of reconstruction is this, and who benefits from it?

More here.

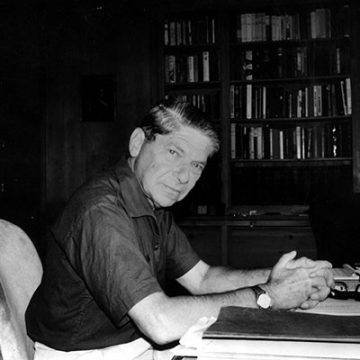

A Drinker of Infinity: Arthur Koestler’s life and work embodied the existential dilemmas of our age

Theodore Dalrymple in The City Journal (2007 issue):

Someone who had known Arthur Koestler told me a little story about him. Koestler was playing Scrabble with his wife, and he put the word VINCE down on the board.

Someone who had known Arthur Koestler told me a little story about him. Koestler was playing Scrabble with his wife, and he put the word VINCE down on the board.

“Arthur,” said his wife, “what does ‘vince’ mean?”

Koestler, who never lost his strong Hungarian accent but whose mastery of English was such that he was undoubtedly one of the twentieth century’s great prose writers in the language, replied (one can just imagine with what light in his eyes): “To vince is to flinch slightly viz pain.”

…Throughout Dialogue with Death, Koestler raises profound existential questions. He becomes almost mystical, foreshadowing his later interests; after his release, he dreams of the Seville prison. “Often when I wake at night I am homesick for my cell in the death-house . . . and I feel I have never been so free as I was then.” He continues:

This is a very curious feeling indeed. We lived an unusual life. . . . The constant nearness of death weighed us down and at the same time gave us a feeling of weightless floating. We were without responsibility. Most of us were not afraid of death, only of the act of dying; and there were times when we overcame even this fear. At such moments we were free—men without shadows, dismissed from the ranks of the mortal; it was the most complete experience of freedom that can be granted a man.

The man who wrote those words was not likely to remain a Communist (as he was when he wrote them).

More here.

Grail, a deep-pocketed startup, shows ‘impressive,’ if early, results for cancer blood test

Matthew Herper in Stat:

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The data show that the company’s test can detect cancer in the blood with relatively few false positives and that it is fairly accurate at identifying where in the body the tumor was found. Another abstract seems to show that the test is more likely to identify tumors if they are more deadly. One big worry with a cancer blood test is that it would lead to large numbers of patients being diagnosed with mild tumors that would be better off untreated.

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The data show that the company’s test can detect cancer in the blood with relatively few false positives and that it is fairly accurate at identifying where in the body the tumor was found. Another abstract seems to show that the test is more likely to identify tumors if they are more deadly. One big worry with a cancer blood test is that it would lead to large numbers of patients being diagnosed with mild tumors that would be better off untreated.

…Grail is running a preliminary study called the Circulating Cell-Free Genome Atlas (CCGA), which is being conducted in 15,000 patients. The goal from the beginning was to use this study to optimize a diagnostic test. This would then be tested in two more studies: one of 100,000 women enrolled at the time of their first mammogram, and a second of 50,000 men and women between the ages of 50 and 77 in London who have not been diagnosed with cancer. These huge studies are one reason Grail has raised so much money. But the data being reported at the ASCO meeting are from a tiny sliver of that first study: an initial analysis of 2,301 participants from the training phase of the sub-study, including 1,422 people known to have cancer and 879 who have not been diagnosed. These data are being used to pick exactly what test Grail will run.

More here.

Sunday Poem

The Hotel

My room is like a cage.

The sun hangs its arms through the bars.

But I, I want to smoke,

to curl shapes in the air;

I light my cigarette

on the day’s fire.

I do not want to work —

I want to smoke.

L’hotel

Ma chambre a la forme d’une cage,

Le soleil passe son bras par la fenêtre.

Mais moi qui veux fumer pour faire des mirages,

J’allume au feu du jour ma cigarette,

Je ne veux pas travailler — je veux fumer.

.

by Guillaume Apollinaire

translated by Marilyn McCabe

Murray Gell-Mann (1929 – 2019)

Machiko Kyo (1924 – 2019)

Leon Redbone (1949 – 2019)

Saturday, June 1, 2019

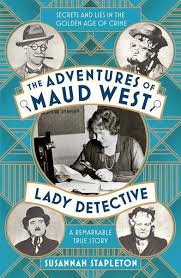

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective

Lucy Lethbridge at Literary Review:

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers.

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers.

more here.

Head to Head Philosophy

Terry Eagleton at The Guardian:

The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio.

The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio.

Rée is too subtle a thinker to reduce this quarrel to Reason versus Superstition, but AC Grayling has no such qualms. His The History of Philosophy (note the authoritative “The”) sees no dark side to the cult of Reason. And if reason can do little wrong, religion can do nothing right.

more here.

The False Promise of Enlightenment

Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review:

Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review:

For Shoshana Zuboff, the author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, the status quo is nothing short of pre-apocalyptic. Her book may be the most perfect specimen yet of a genre—let’s call it the social-science horror-memoir—fated to expand. She folds subjective experiences of dread into projected scenarios of immiseration, collective disempowerment, and likely violence—an unavoidable conclusion except by treading a narrow path whose coordinates she concedes are hard to discern. David Wallace-Welles’s The Uninhabited Earth (2019) and Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright’s Climate Leviathan (2018) follows this model, as does David Runciman’s How Democracy Ends (2018).

In Zuboff’s case, the story begins literally with her family’s house burning down and her efforts to reconstruct a sense of home in its wake. The death of her husband, to whom the book is dedicated, as well as her German editor, Frank Schirrmacher, also cast an understandably long shadow. Her 688-page book is often less analysis than gut-wrenching scream—a sometimes moving, often exasperating, attempt at mourning what she sees as a passing relationship to our innermost selves.

She implores us to fight the “coup from above” being staged by Google and other tech giants. The book is self-conscious agitprop, designed to “rekindle the sense of outrage and loss over what is being taken from us.” It resonates with the ash-sifting moment around the end of World War II, and there are analogies to the highly personal political interventions of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (1944), B. F. Skinner’s Walden Two (1948), and Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). Indeed, Zuboff likens herself freely to Arendt, plumbing the present to find the origins of a new threat which, like totalitarianism, is all-consuming but which takes the new forms of a “muted, sanitized tyranny.”

More here.