Amy Sorkin in The New Yorker:

As Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi roamed Normandy on Thursday (she had brought along a contingent of dozens of members of Congress for the official commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of D Day, including veterans from both sides of the aisle), her party was debating what it meant to want someone behind bars. Was it too tough, or not tough enough? Politico had reported that, in a meeting of “top Democrats,” on Tuesday night, Representative Jerrold Nadler, of New York, had argued in favor of having the Judiciary Committee, which he chairs, begin proceedings for the impeachment of President Donald Trump. Politico cited “multiple Democratic sources familiar with the meeting” who said that Pelosi demurred, telling Nadler, “I don’t want to see him impeached. I want to see him in prison.”

As Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi roamed Normandy on Thursday (she had brought along a contingent of dozens of members of Congress for the official commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of D Day, including veterans from both sides of the aisle), her party was debating what it meant to want someone behind bars. Was it too tough, or not tough enough? Politico had reported that, in a meeting of “top Democrats,” on Tuesday night, Representative Jerrold Nadler, of New York, had argued in favor of having the Judiciary Committee, which he chairs, begin proceedings for the impeachment of President Donald Trump. Politico cited “multiple Democratic sources familiar with the meeting” who said that Pelosi demurred, telling Nadler, “I don’t want to see him impeached. I want to see him in prison.”

How did “lock him up” become a motto for forbearance and patience? The logic here is that it is constitutionally complicated to indict a sitting President. Indeed, Robert Mueller, the special counsel whose investigation of Russian meddling in the election and related matters is now closed, believed that Justice Department guidance precluded him from making such a move. (If he had done so, the crime would almost certainly have concerned obstruction of justice, rather than collusion.) The calculation would be different, obviously, if Trump were not President. And, as it happens, there is an election next year, which could lead, fairly quickly, to his exit from the White House. In other words, the way to hold him to account criminally is to first hold him to account electorally.

But, others in the Democratic Party say, impeachment is also a way to remove a President from office. That is, indeed, the means to do so that the Constitution gives to Congress. The Democrats view Pelosi as overly cautious. Trump, being a bully, has begun insulting Pelosi in terms that he apparently thinks will get those close to her to turn against her.

More here.

You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer

You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer  Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before?

Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before? “Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis.

“Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis.  They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the

They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the  Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s.

Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s. In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.”

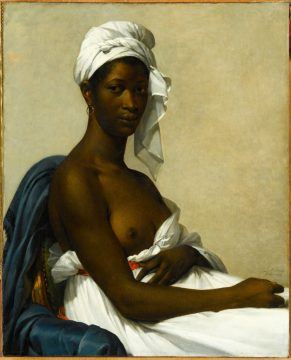

In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.” For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent

For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent  If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,  Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems.

Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems. Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes,” says EM Forster in A Room With a View, adapting a quote from

Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes,” says EM Forster in A Room With a View, adapting a quote from  In addition to resources, the advocates of cultured meat have a philosophy ready to hand. Many of them are self-described utilitarians, readers of the works of philosopher Peter Singer, in particular his 1975 book

In addition to resources, the advocates of cultured meat have a philosophy ready to hand. Many of them are self-described utilitarians, readers of the works of philosopher Peter Singer, in particular his 1975 book  The painting made headlines last November for the price it took at auction, though this datum doesn’t interest me. More significant is the return of a too-little-revived film that documents Portrait of an Artist’s charged iterations and the circumstances surrounding them. After watching A Bigger Splash a few weeks before its premiere at Cannes in 1974, Hockney said he was “utterly shattered” by it, his anguish spiked further by a film-director friend who favorably—if somewhat incongruously—likened it to “a real Sunday Bloody Sunday,” John Schlesinger’s astute, London-set, big-studio-backed 1971 drama about a love triangle (two men, one woman). More felicitous comparisons might include Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971), a gay XXX landmark in which a Fire Island natatorium becomes a pleasure palace, not to mention Robert Kramer’s Milestones (1975), an epic dirge on the failed dreams of the New Left in the US, which was also devised as a docufiction. (Hazan and Mingay would return to this genre with 1980’s Rude Boy, centering on the Clash.) But as for movies about making (art) and unmaking (a relationship), I can think of none better, or more sinuous—as serpentine as Hockney’s enunciation of a favorite descriptor.

The painting made headlines last November for the price it took at auction, though this datum doesn’t interest me. More significant is the return of a too-little-revived film that documents Portrait of an Artist’s charged iterations and the circumstances surrounding them. After watching A Bigger Splash a few weeks before its premiere at Cannes in 1974, Hockney said he was “utterly shattered” by it, his anguish spiked further by a film-director friend who favorably—if somewhat incongruously—likened it to “a real Sunday Bloody Sunday,” John Schlesinger’s astute, London-set, big-studio-backed 1971 drama about a love triangle (two men, one woman). More felicitous comparisons might include Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971), a gay XXX landmark in which a Fire Island natatorium becomes a pleasure palace, not to mention Robert Kramer’s Milestones (1975), an epic dirge on the failed dreams of the New Left in the US, which was also devised as a docufiction. (Hazan and Mingay would return to this genre with 1980’s Rude Boy, centering on the Clash.) But as for movies about making (art) and unmaking (a relationship), I can think of none better, or more sinuous—as serpentine as Hockney’s enunciation of a favorite descriptor.