Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

The photos of Óscar and Valeria Ramírez, migrants from El Salvador, drowned in the Rio Grande as they tried to cross into the USA, are haunting and distressing, and have sparked outrage and anger in America. Four years ago, images of the Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach similarly shocked and horrified Europe.

The photos of Óscar and Valeria Ramírez, migrants from El Salvador, drowned in the Rio Grande as they tried to cross into the USA, are haunting and distressing, and have sparked outrage and anger in America. Four years ago, images of the Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach similarly shocked and horrified Europe.

These deaths are neither accidents nor isolated cases. They are the consequences of immigration policy, on both sides of the Atlantic, that aims at ‘deterring’ migrants. A little boy lying dead on a beach, a father and daughter face down in a river – that is what deterrence looks like.

At least 175 people, including 13 children, have died on the US-Mexican border this year alone. More than 2000 have died over the past 5 years. The European figures are more startling still. Almost 600 people have drowned in the Mediterranean so far this year. Since 1993, some 35,000 have died. Thousands more, perhaps tens of thousands more, will have perished in silence, their deaths never recorded. Alan Kurdi and Óscar and Valeria Ramírez are merely the cases in which the imagery was shocking enough to have caught public attention.

Immigration controls today mean not simply a border guard asking you for your papers. They constitute a violent, coercive, militarised system of control. When a journalist from Der Speigel magazine visited the control room of Frontex, the EU’s border agency, he observed that the language used was that of ‘defending Europe against an enemy’.

More here.

March 2019: a woman is standing in front of some Swatch watches on a daytime TV antiques show. The presenter asks which is her favourite. “Probably this one,” she answers, pointing to a watch adorned with a cartoon barking mutt. “I just like the dog – it makes me smile.” The story of how Keith Haring’s symbols became so ubiquitous that they ended up on the wrists of Middle England as much as on the bedroom walls of 1980s Aids activists is both the contradiction and the genius of the New York street artist, whose star burned fast and acid bright. Tate Liverpool’s superb retrospective traces Haring’s ten-year flight from street artist to global consumer brand, from scrawling on the subway to painting the Berlin Wall, and details the turbulent political backdrop behind his work. We know many of his motifs well – the dog, the crawling baby, the three-eyed face – his thick black lines and dancing figures, but there’s nothing superficial about these deceptively simple scrawls.

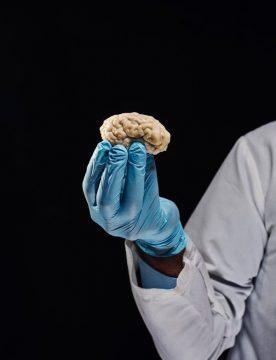

March 2019: a woman is standing in front of some Swatch watches on a daytime TV antiques show. The presenter asks which is her favourite. “Probably this one,” she answers, pointing to a watch adorned with a cartoon barking mutt. “I just like the dog – it makes me smile.” The story of how Keith Haring’s symbols became so ubiquitous that they ended up on the wrists of Middle England as much as on the bedroom walls of 1980s Aids activists is both the contradiction and the genius of the New York street artist, whose star burned fast and acid bright. Tate Liverpool’s superb retrospective traces Haring’s ten-year flight from street artist to global consumer brand, from scrawling on the subway to painting the Berlin Wall, and details the turbulent political backdrop behind his work. We know many of his motifs well – the dog, the crawling baby, the three-eyed face – his thick black lines and dancing figures, but there’s nothing superficial about these deceptively simple scrawls. A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch.

A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch. Leonard Benardo in The American Progress:

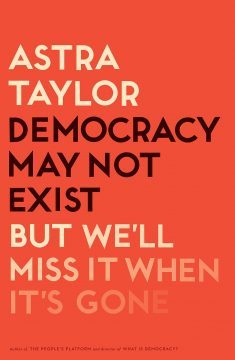

Leonard Benardo in The American Progress: Eric Foner in The Nation:

Eric Foner in The Nation: Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books:

Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books: Martin Jay in The Point:

Martin Jay in The Point: Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure.

Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure. Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.”

Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.” B

B It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,

It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,  On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for.

On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for. In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon.

In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon. “What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said.

“What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said.