Elizabeth Catte in a Boston Review Forum:

Elizabeth Catte in a Boston Review Forum:

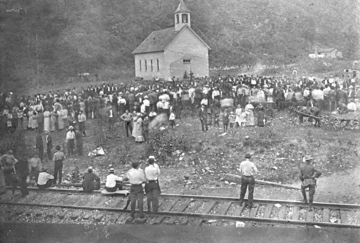

Rural spaces are often thought of as places absent of things, from people of color to modern amenities to radical politics. The truth, as usual, is more complicated. The parents and grandparents of my childhood friends were union organizers; when my grandfather moved to East Tennessee, he went from a world of communist coal miners to the backyard of one of the most important incubators of the civil rights movement, the Highlander Research and Education Center. I now organize with people whose families have fought against economic exploitation for generations. From my vantage point in West Virginia and southwestern Virginia, what is old is new again: the revival of a labor movement, the fight against extractive capitalism, the struggle against corporate money in politics, and the continuation of women’s grassroots leadership.

The question of whether mainstream liberal opinion is shifting further left has been hotly debated in the national press after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won the primary for New York’s fourteenth congressional district with grassroots momentum and a socialist-friendly platform. Both conservative and liberal commentators predicted disaster, framing the twenty-eight-year-old rising political star as a gift to Donald Trump. Former Democratic congressman–turned–political pundit Steve Israel warned, “A message that resonates in downtown Brooklyn, New York, could backfire in Brooklyn, Iowa.”

More here.

Where once Europeans and North Americans might have turned to religion or philosophy to understand themselves, increasingly they are embracing psychotherapy and its cousins. The mindfulness movement is a prominent example of this shift in cultural habits of self-reflection and interrogation. Instead of engaging in deliberation about oneself, what the arts of mindfulness have in common is a certain mode of attending to present events – often described as a ‘nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment’. Practitioners are discouraged from engaging with their experiences in a critical or evaluative manner, and often they’re explicitly instructed to disregard the content of their own thoughts.

Where once Europeans and North Americans might have turned to religion or philosophy to understand themselves, increasingly they are embracing psychotherapy and its cousins. The mindfulness movement is a prominent example of this shift in cultural habits of self-reflection and interrogation. Instead of engaging in deliberation about oneself, what the arts of mindfulness have in common is a certain mode of attending to present events – often described as a ‘nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment’. Practitioners are discouraged from engaging with their experiences in a critical or evaluative manner, and often they’re explicitly instructed to disregard the content of their own thoughts. The new initiative was first announced by India’s right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at a state executive meeting in its Bhopal headquarters in April 2016. “The state will be made responsible for the happiness and tolerance of its citizens,” declared Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the former chief minister of Madhya Pradesh and a BJP-celebrated yoga enthusiast. “We will rope in psychologists to counsel people on how to always be happy.” They decided on a budget of $567,000 and a purpose. “Happiness will not come into the lives of people merely with materialistic possessions or development,” Chouhan explained, “but by infusing positivity in their lives so that they don’t take extreme steps like suicide in distress.”

The new initiative was first announced by India’s right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at a state executive meeting in its Bhopal headquarters in April 2016. “The state will be made responsible for the happiness and tolerance of its citizens,” declared Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the former chief minister of Madhya Pradesh and a BJP-celebrated yoga enthusiast. “We will rope in psychologists to counsel people on how to always be happy.” They decided on a budget of $567,000 and a purpose. “Happiness will not come into the lives of people merely with materialistic possessions or development,” Chouhan explained, “but by infusing positivity in their lives so that they don’t take extreme steps like suicide in distress.” On the college campus where I have been living, the students dress in a style I do not understand. Continuous with what we wore fifteen years ago and subtly different, it is both hipster and not. American Apparel has filed for bankruptcy, but in cities and towns across the US the styles forged a decade ago at the epicenters of bohemia still filter out. Urban Outfitters is going strong. In Zürich, on the banks of the Limmat, elaborate tattoos cover the bodies of the children of Swiss bounty. The French use Brooklyn as a metonym for hip. In this context, in such saturation, hipster can no longer stand for anything, except perhaps the attempt or ambition to look cool. But since coolness venerates its own repudiation most of all, every considered choice bears hipster’s trace. Hipster is everything and nothing—and so it is nothing.

On the college campus where I have been living, the students dress in a style I do not understand. Continuous with what we wore fifteen years ago and subtly different, it is both hipster and not. American Apparel has filed for bankruptcy, but in cities and towns across the US the styles forged a decade ago at the epicenters of bohemia still filter out. Urban Outfitters is going strong. In Zürich, on the banks of the Limmat, elaborate tattoos cover the bodies of the children of Swiss bounty. The French use Brooklyn as a metonym for hip. In this context, in such saturation, hipster can no longer stand for anything, except perhaps the attempt or ambition to look cool. But since coolness venerates its own repudiation most of all, every considered choice bears hipster’s trace. Hipster is everything and nothing—and so it is nothing.

What if the dominant discourse on poverty is just wrong? What if the problem isn’t that poor people have bad morals – that they’re lazy and impulsive and irresponsible and have no family values – or that they lack the skills and smarts to fit in with our shiny 21st-century economy? What if the problem is that poverty is profitable? These are the questions at the heart of Evicted, Matthew Desmond’s extraordinary ethnographic study of tenants in low-income housing in the deindustrialised middle-sized city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

What if the dominant discourse on poverty is just wrong? What if the problem isn’t that poor people have bad morals – that they’re lazy and impulsive and irresponsible and have no family values – or that they lack the skills and smarts to fit in with our shiny 21st-century economy? What if the problem is that poverty is profitable? These are the questions at the heart of Evicted, Matthew Desmond’s extraordinary ethnographic study of tenants in low-income housing in the deindustrialised middle-sized city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Philip Roth once called Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man and The Truce – usually published as one volume – “one of the century’s truly necessary books”. If you’ve read Levi, the only quibble you could make with Roth is that he’s too restrictive in only referring to the 20th century. It’s impossible to imagine a time when the two won’t be essential, both because of what they describe and the clarity and moral force of Levi’s writing. Reading him is not a passive process. It isn’t just that he makes us see and understand the terrible crimes that he himself saw in

Philip Roth once called Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man and The Truce – usually published as one volume – “one of the century’s truly necessary books”. If you’ve read Levi, the only quibble you could make with Roth is that he’s too restrictive in only referring to the 20th century. It’s impossible to imagine a time when the two won’t be essential, both because of what they describe and the clarity and moral force of Levi’s writing. Reading him is not a passive process. It isn’t just that he makes us see and understand the terrible crimes that he himself saw in  Memories make us who we are. They shape our understanding of the world and help us to predict what’s coming. For more than a century, researchers have been working to understand how memories are formed and then fixed for recall in the days, weeks or even years that follow. But those scientists might have been looking at only half the picture. To understand how we remember, we must also understand how, and why, we forget.

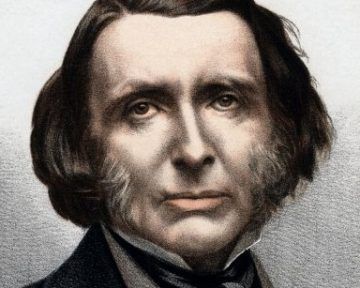

Memories make us who we are. They shape our understanding of the world and help us to predict what’s coming. For more than a century, researchers have been working to understand how memories are formed and then fixed for recall in the days, weeks or even years that follow. But those scientists might have been looking at only half the picture. To understand how we remember, we must also understand how, and why, we forget. Ruskin was twenty-six when, in 1845, on his third trip to Venice but seeing the paintings of Tintoretto there for the first time, he wrote excitedly to his father and urged him to put the artist he called Tintoret “at the top, top, top of everything”. On first walking into La Scuola Grande Di San Rocco, today’s visitor is still likely to feel some of the astonishment that gripped Ruskin. Tintoretto spent more than twenty years decorating the Sala Superiore (“Upper Hall”) and he was given free rein by his patrons. He could express himself freely and was less bound by the need to compete with his rival Veronese. Beginning with magnificent ceiling paintings and aware of the prestige he could achieve, Tintoretto offered to paint the sala’s walls for a modest annuity. The result, an astonishing torrent of exuberant inventiveness and extravagant theatricality, was a revelation for Ruskin and caused him to completely rethink the completion of his Modern Painters work: “I have been quite upset in all my calculations by that rascal Tintoret – he has shown me some totally new fields of art and altered my feelings in many respects.” His focus on landscape painting now shifted to the religious painters of the Old Masters and Emma Sdengo, in Looking at Tintoretto with John Ruskin, sees Turner – who had studied Tintoretto – as priming Ruskin’s discovery of “that rascal Tintoret”.

Ruskin was twenty-six when, in 1845, on his third trip to Venice but seeing the paintings of Tintoretto there for the first time, he wrote excitedly to his father and urged him to put the artist he called Tintoret “at the top, top, top of everything”. On first walking into La Scuola Grande Di San Rocco, today’s visitor is still likely to feel some of the astonishment that gripped Ruskin. Tintoretto spent more than twenty years decorating the Sala Superiore (“Upper Hall”) and he was given free rein by his patrons. He could express himself freely and was less bound by the need to compete with his rival Veronese. Beginning with magnificent ceiling paintings and aware of the prestige he could achieve, Tintoretto offered to paint the sala’s walls for a modest annuity. The result, an astonishing torrent of exuberant inventiveness and extravagant theatricality, was a revelation for Ruskin and caused him to completely rethink the completion of his Modern Painters work: “I have been quite upset in all my calculations by that rascal Tintoret – he has shown me some totally new fields of art and altered my feelings in many respects.” His focus on landscape painting now shifted to the religious painters of the Old Masters and Emma Sdengo, in Looking at Tintoretto with John Ruskin, sees Turner – who had studied Tintoretto – as priming Ruskin’s discovery of “that rascal Tintoret”.

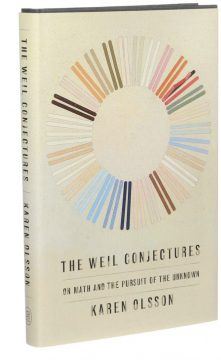

At the 1994 reception for the prestigious Kyoto Prize, awarded for achievements that contribute to humanity, the French mathematician André Weil turned to his fellow honoree, the film director Akira Kurosawa, and said: “I have a great advantage over you. I can love and admire your work, but you cannot love and admire my work.”

At the 1994 reception for the prestigious Kyoto Prize, awarded for achievements that contribute to humanity, the French mathematician André Weil turned to his fellow honoree, the film director Akira Kurosawa, and said: “I have a great advantage over you. I can love and admire your work, but you cannot love and admire my work.” Scientists can’t quite agree on how to define “life,” but that hasn’t stopped them from studying it, looking for it elsewhere, or even trying to create it. Kate Adamala is one of a number of scientists engaged in the ambitious project of trying to create living cells, or something approximating them, starting from entirely non-living ingredients. Impressive progress has already been made. Designing cells from scratch will have obvious uses is biology and medicine, but also allow us to build biological robots and computers, as well as helping us understand how life could have arisen in the first place, and what it might look like on other planets.

Scientists can’t quite agree on how to define “life,” but that hasn’t stopped them from studying it, looking for it elsewhere, or even trying to create it. Kate Adamala is one of a number of scientists engaged in the ambitious project of trying to create living cells, or something approximating them, starting from entirely non-living ingredients. Impressive progress has already been made. Designing cells from scratch will have obvious uses is biology and medicine, but also allow us to build biological robots and computers, as well as helping us understand how life could have arisen in the first place, and what it might look like on other planets. In August 1976, The Nation published an essay that rocked the US political establishment, both for what it said and for who was saying it. “

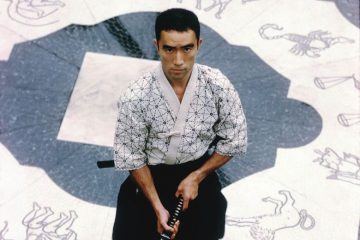

In August 1976, The Nation published an essay that rocked the US political establishment, both for what it said and for who was saying it. “ Star, the short novella Mishima published in November 1960, is little known in Japan, buried as it is under the weight of the grander achievements in the forty-two volumes of his Complete Works. But it is now open to rediscovery thanks to an adroit, colloquial translation into American English by Sam Bett. It offers us a snapshot of a twenty-three-year-old, up-and-coming movie star, Rikio “Richie” Mizuno. Paraded in a string of formulaic films, swooned over by his many female fans, Rikio and the studio who manage him carefully groom his image. When a fan intrudes on the set and disrupts a take to throw herself at “Richie”, the director is at first furious, then ponders whether her intervention couldn’t be built into the script. But she can’t act, so she is quickly cut again and promptly attempts suicide, before the studio spin the story as “Richie” intervening to save her life.

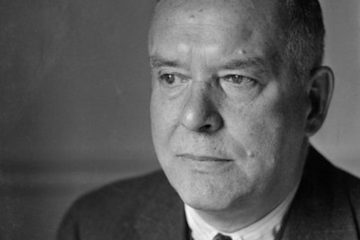

Star, the short novella Mishima published in November 1960, is little known in Japan, buried as it is under the weight of the grander achievements in the forty-two volumes of his Complete Works. But it is now open to rediscovery thanks to an adroit, colloquial translation into American English by Sam Bett. It offers us a snapshot of a twenty-three-year-old, up-and-coming movie star, Rikio “Richie” Mizuno. Paraded in a string of formulaic films, swooned over by his many female fans, Rikio and the studio who manage him carefully groom his image. When a fan intrudes on the set and disrupts a take to throw herself at “Richie”, the director is at first furious, then ponders whether her intervention couldn’t be built into the script. But she can’t act, so she is quickly cut again and promptly attempts suicide, before the studio spin the story as “Richie” intervening to save her life. Now regarded as a towering figure of modern verse, Wallace Stevens was probably better known as an insurance man for much of his adult life. But during a long and comfortable career at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, he also wrote poems that cut to the very heart of existence. Like his near contemporary (and sometimes rival)

Now regarded as a towering figure of modern verse, Wallace Stevens was probably better known as an insurance man for much of his adult life. But during a long and comfortable career at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, he also wrote poems that cut to the very heart of existence. Like his near contemporary (and sometimes rival)