Meera Subramanian in Nature:

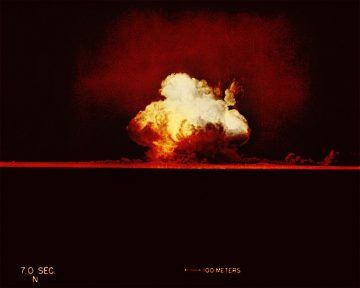

Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time.

Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time.

This lake is unusually deep for its size so its waters never fully mix, which leaves its bottom undisturbed by burrowing worms or currents. Layers of sediment accumulate like tree rings, creating an archive reaching back nearly 1,000 years. In high fidelity, it has captured evidence of the Iroquois people, who cultivated maize (corn) along the lake’s banks at least 750 years ago, and then of the European settlers, who began farming and chopping down trees more than five centuries later. Now, scientists are looking for much more recent, and significant, signs of upheaval tied to humans. Core samples taken from the lake bottom “should translate into a razor-sharp signal”, says Francine McCarthy, a micropalaeontologist at nearby Brock University in St Catherines, Ontario, “and not one blurred by clams mushing it about.” McCarthy has been studying the lake since the 1980s, but she is looking at it now from a radical new perspective.

Crawford Lake is one of ten sites around the globe that researchers are studying as potential markers for the start of the Anthropocene, an as-yet-unofficial designation that is being considered for inclusion in the geological time scale.

More here.

“A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General

“A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General  My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a

My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a  One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate.

One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate. The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with

The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with  It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why:

It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why:

Will Fitzgibbon over at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists:

Will Fitzgibbon over at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists:

“A period is something I deal with, without thinking about it particularly, or rather I think of it with a part of my mind that deals with routine problems. It is the same part of my mind that deals with the problem of routine cleanliness.” In Doris Lessing’s 1962 novel, The Golden Notebook, the protagonist, Anna, worries about her period and how it will affect the integrity of her writing. In the early 1960s, it was unusual and brave for a work of fiction to mention menstruation, let alone explore it in such detail. Broadly speaking, in mainstream fiction, examples of menstruation are few and far between.

“A period is something I deal with, without thinking about it particularly, or rather I think of it with a part of my mind that deals with routine problems. It is the same part of my mind that deals with the problem of routine cleanliness.” In Doris Lessing’s 1962 novel, The Golden Notebook, the protagonist, Anna, worries about her period and how it will affect the integrity of her writing. In the early 1960s, it was unusual and brave for a work of fiction to mention menstruation, let alone explore it in such detail. Broadly speaking, in mainstream fiction, examples of menstruation are few and far between. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula encompasses more than 16,000 square miles of northern hardwood forest, broken here and there by hardscrabble towns whose year-round population is slowly bleeding away. In “Hunter’s Moon,”

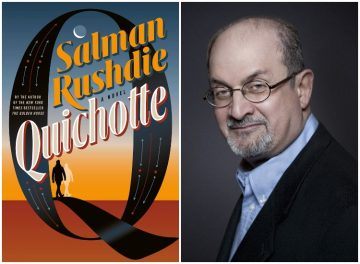

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula encompasses more than 16,000 square miles of northern hardwood forest, broken here and there by hardscrabble towns whose year-round population is slowly bleeding away. In “Hunter’s Moon,”  Opening a new Salman Rushdie novel after reading almost any other contemporary writer is like stepping off a plane in Mumbai, or New York in a heatwave: it immediately hits you how much milder and quieter things are back home. Quichotte overwhelms you from the first page with a lightning storm of ideas and a monsoon of exuberant prose. Dissonance, multiplicity, excess: these are Rushdie’s themes and his method. If you happen to experience, along with one of his characters, ‘a certain dizziness brought on by the merging of the real and the fictional, the paranoiac and the actual outlook’ – well, that’s all part of the fun.

Opening a new Salman Rushdie novel after reading almost any other contemporary writer is like stepping off a plane in Mumbai, or New York in a heatwave: it immediately hits you how much milder and quieter things are back home. Quichotte overwhelms you from the first page with a lightning storm of ideas and a monsoon of exuberant prose. Dissonance, multiplicity, excess: these are Rushdie’s themes and his method. If you happen to experience, along with one of his characters, ‘a certain dizziness brought on by the merging of the real and the fictional, the paranoiac and the actual outlook’ – well, that’s all part of the fun. Politicians and pundits from all quarters often lament democracy’s polarized condition.

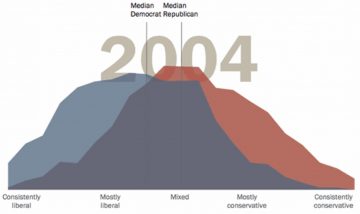

Politicians and pundits from all quarters often lament democracy’s polarized condition.