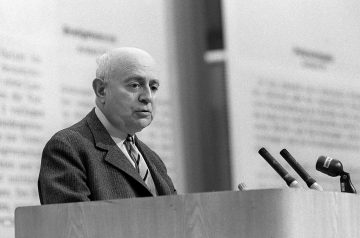

Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

There is no question that radical right-wing fringe phenomena have been normalized under Donald Trump, most spectacularly when he claimed that there were good people on both sides in the Charlottesville riots. What used to be called the lunatic fringe in American politics is being made respectable by such pronouncements, as well as by the euphemism of “alt-right” itself, a term innocuous enough to disguise its white supremacist ideology. Adorno also warned that the afterlife of fascist tendencies within democracy is more dangerous than the afterlife of fascist tendencies against democracy. Today we face a situation where Adorno’s distinction has been cashed in. Tendencies from within, brilliantly analyzed by Wendy Brown in her 2015 book Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, are merging in the US with outright tendencies against democracy. The Trump regime participates in both. Just think of the Republicans’ systematic attacks on voting rights through gerrymandering, recently legitimized by the Supreme Court. Or compare Mark Zuckerberg’s motto “move fast and break things” with Trump’s daily practice of attacking and dismantling American governmental institutions, a practice that is fully in sync with Steve Bannon’s demand to “deconstruct the administrative state” and with Breitbart’s call to attack the “Democrat media complex” online. Trump uses Twitter and his fake “fake news” mantra to gaslight the electorate, while much of the real deconstruction of governmental institutions regarding the law and the constitution, health care, the environment, housing, foreign policy, and climate change rarely catches the headlines in any sustained fashion. While right-wing parties in the European Union are gaining ground, with few exceptions they are not (yet) the mainstream. In the United States, the Republicans are the mainstream and further to the right than either the AfD in Germany or the latest incarnation of the National Front in France.

More here.

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic  Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go.

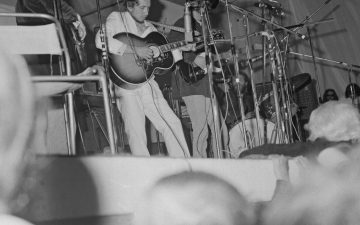

Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go. Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory.

Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory. It’s hard to overstate the significance of

It’s hard to overstate the significance of  On an October morning in 2006, a young man backed his truck into the driveway of a one-room schoolhouse. He walked into the school and after ordering the boy students, the teacher and a few other adults to leave, he lined up 10 girls, ages 9 to 13, and shot them. The mindless horror of that attack drew intense and sustained press as well as, later on, books and film. Although there had been two other school shootings only a few days earlier, what made this massacre especially notable was the fact that its landscape was an Amish community — notoriously peaceful and therefore the most unlikely venue for such violence.

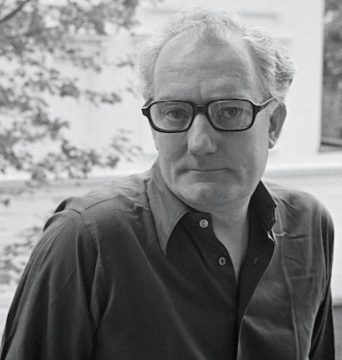

On an October morning in 2006, a young man backed his truck into the driveway of a one-room schoolhouse. He walked into the school and after ordering the boy students, the teacher and a few other adults to leave, he lined up 10 girls, ages 9 to 13, and shot them. The mindless horror of that attack drew intense and sustained press as well as, later on, books and film. Although there had been two other school shootings only a few days earlier, what made this massacre especially notable was the fact that its landscape was an Amish community — notoriously peaceful and therefore the most unlikely venue for such violence. When I met him, Bryan Magee was nearly 89, marvellously lucid, curious to hear about my time at Oxford, and paralysed from the waist down: in many ways the ideal interviewee. For a generation of young viewers, Magee’s legendary television series about philosophy were a baptism in the waters of the subject, and he the urbane and worldly gatekeeper to a realm of theoretic abstraction and grounded, vigorous discussion such as had never before been entered—a watershed moment in a primetime slot.

When I met him, Bryan Magee was nearly 89, marvellously lucid, curious to hear about my time at Oxford, and paralysed from the waist down: in many ways the ideal interviewee. For a generation of young viewers, Magee’s legendary television series about philosophy were a baptism in the waters of the subject, and he the urbane and worldly gatekeeper to a realm of theoretic abstraction and grounded, vigorous discussion such as had never before been entered—a watershed moment in a primetime slot. India’s decision two days ago to revoke most of Article 370 of its constitution and annex the part of Jammu & Kashmir it holds has sent Subcontinental and transcontinental punditocracy into a frenzy of analysis, interpretation, speculation, and prediction. Several scenarios have risen to the surface.

India’s decision two days ago to revoke most of Article 370 of its constitution and annex the part of Jammu & Kashmir it holds has sent Subcontinental and transcontinental punditocracy into a frenzy of analysis, interpretation, speculation, and prediction. Several scenarios have risen to the surface. In recent years, biology’s “nature vs. nurture” war has reemerged with advanced weapons, although the central questions have not changed: What makes us human? Why are we different from one another? Nonetheless, the methods used to address them have undergone several revolutions. We now benefit from hundreds of twin and adoption studies, which have provided heritability estimates for dozens of characteristics relating to human behavior and wellness. Simultaneously, we are reaping the benefits of technological breakthroughs that have made it possible to screen thousands of individuals to uncover genes associated with particular traits. Thanks to this, we have been able to correlate genetic signatures with a growing list of physical (e.g., height, skin color), physiological (e.g., risk for type-2 diabetes, hypertension), and behavioral (e.g., risk for depression, autism) traits. At the same time, epidemiology, psychology, and sociology continue to demonstrate the pliability of the human experience across populations, and we continue to learn more about the social forces that create vast differences in the human experience.

In recent years, biology’s “nature vs. nurture” war has reemerged with advanced weapons, although the central questions have not changed: What makes us human? Why are we different from one another? Nonetheless, the methods used to address them have undergone several revolutions. We now benefit from hundreds of twin and adoption studies, which have provided heritability estimates for dozens of characteristics relating to human behavior and wellness. Simultaneously, we are reaping the benefits of technological breakthroughs that have made it possible to screen thousands of individuals to uncover genes associated with particular traits. Thanks to this, we have been able to correlate genetic signatures with a growing list of physical (e.g., height, skin color), physiological (e.g., risk for type-2 diabetes, hypertension), and behavioral (e.g., risk for depression, autism) traits. At the same time, epidemiology, psychology, and sociology continue to demonstrate the pliability of the human experience across populations, and we continue to learn more about the social forces that create vast differences in the human experience. We’ve got these bodies and these brains, which work okay, but we also have minds. We see, we hear, we think, we feel, we plan, we act, we do; we’re conscious. Viewed from the outside, you see a reasonably finely tuned mechanism. From the inside, we all experience ourselves as having a mind, as feeling, thinking, experiencing, being, which is pretty central to our conception of ourselves. It also raises any number of philosophical and scientific problems. When it comes to explaining the objective stuff from the outside—the behavior and so on—you put together some neural and computational mechanisms, and we have a paradigm for explaining those.

We’ve got these bodies and these brains, which work okay, but we also have minds. We see, we hear, we think, we feel, we plan, we act, we do; we’re conscious. Viewed from the outside, you see a reasonably finely tuned mechanism. From the inside, we all experience ourselves as having a mind, as feeling, thinking, experiencing, being, which is pretty central to our conception of ourselves. It also raises any number of philosophical and scientific problems. When it comes to explaining the objective stuff from the outside—the behavior and so on—you put together some neural and computational mechanisms, and we have a paradigm for explaining those.

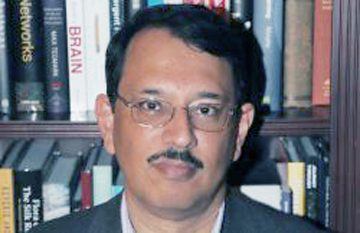

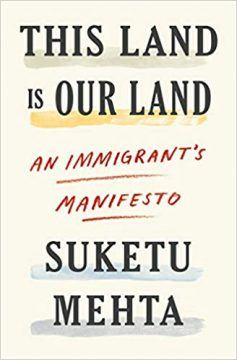

“I claim the right to the United States, for myself and my children and my uncles and cousins, by manifest destiny.” The claimant is Suketu Mehta, in This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. The reference to manifest destiny isn’t merely trolling. Mehta’s thesis is that extensive migration from poor parts of the globe to the US is as inevitable and justified as the westward migration that built this country. He goes on:

“I claim the right to the United States, for myself and my children and my uncles and cousins, by manifest destiny.” The claimant is Suketu Mehta, in This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. The reference to manifest destiny isn’t merely trolling. Mehta’s thesis is that extensive migration from poor parts of the globe to the US is as inevitable and justified as the westward migration that built this country. He goes on: When we design a skyscraper we expect it will perform to specification: that the tower will support so much weight and be able to withstand an earthquake of a certain strength.

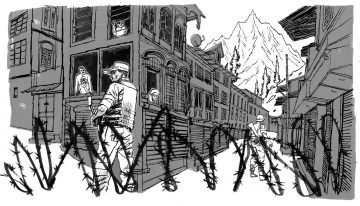

When we design a skyscraper we expect it will perform to specification: that the tower will support so much weight and be able to withstand an earthquake of a certain strength. The cheerleaders for Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India are cheering for Partition redux, a world-class massacre, ethnic cleansing. The brute power of Hindu supremacy has its own logic, and it requires not only that Kashmiris be denied a future but also that they be humiliated and punished for their past sin of not being grateful Indians. While individual Indian Muslims across the country are being lynched for trading beef or

The cheerleaders for Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India are cheering for Partition redux, a world-class massacre, ethnic cleansing. The brute power of Hindu supremacy has its own logic, and it requires not only that Kashmiris be denied a future but also that they be humiliated and punished for their past sin of not being grateful Indians. While individual Indian Muslims across the country are being lynched for trading beef or  The authors find little proof of increasing busyness among the population. Yes, as expected, people were spending far more time on digital devices in 2015 than they were in 2000. But the data provides little evidence that people now spend more time multitasking or that they’re switching more often from one activity to another, which might make our time seem fragmented and frantic.

The authors find little proof of increasing busyness among the population. Yes, as expected, people were spending far more time on digital devices in 2015 than they were in 2000. But the data provides little evidence that people now spend more time multitasking or that they’re switching more often from one activity to another, which might make our time seem fragmented and frantic.

In novels spanning several hundred years of history, Toni Morrison used her historical imagination and her remarkable gifts of language to chronicle the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, and their continuing fallout on the everyday lives of black Americans. Violent, heart-wrenching events occur in her fiction: a runaway slave named Sethe cuts the throat of her baby daughter with a handsaw to spare her the fate she suffered herself as a slave (

In novels spanning several hundred years of history, Toni Morrison used her historical imagination and her remarkable gifts of language to chronicle the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, and their continuing fallout on the everyday lives of black Americans. Violent, heart-wrenching events occur in her fiction: a runaway slave named Sethe cuts the throat of her baby daughter with a handsaw to spare her the fate she suffered herself as a slave (