Meilan Solly in Smithsonian:

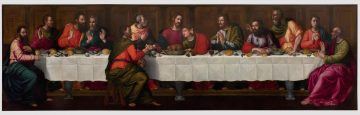

Around 1568, Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli—a self-taught painter who ran an all-woman artists’ workshop out of her convent—embarked on her most ambitious project yet: a monumental Last Supper scene featuring life-size depictions of Jesus and the 12 Apostles.

Around 1568, Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli—a self-taught painter who ran an all-woman artists’ workshop out of her convent—embarked on her most ambitious project yet: a monumental Last Supper scene featuring life-size depictions of Jesus and the 12 Apostles.

As Alexandra Korey writes for the Florentine, Nelli’s roughly 21- by 6-and-a-half foot canvas is remarkable for its challenging composition, adept treatment of anatomy at a time when women were banned from studying the scientific field, and chosen subject. During the Renaissance, the majority of individuals who painted the biblical scene were male artists at the pinnacle of their careers. Per the nonprofit Advancing Women Artists organization, which restores and exhibits works by Florence’s female artists, Nelli’s masterpiece placed her among the ranks of such painters as Leonardo da Vinci, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Pietro Perugino, all of whom created versions of the Last Supper “to prove their prowess as art professionals.”

Despite boasting such a singular display of skill, the panel has long been overlooked. According to Visible: Plautilla Nelli and Her Last Supper Restored, a monograph edited by AWA Director Linda Falcone, Last Supper hung in the refectory (or dining hall) of the artist’s own convent, Santa Caterina, until the house of worship’s dissolution during the Napoleonic suppression of the early 19th century. The Florentine monastery of Santa Maria Novella acquired the painting in 1817, housing it in the refectory before moving it to a new location around 1865. In 1911, scholar Giovanna Pierattini reported, the portable panel was “removed from its stretcher, rolled up and moved to a warehouse, where it remained neglected for almost three decades.”

More here.

Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.”

Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.” It all began with a book review. Last year, I read

It all began with a book review. Last year, I read  A

A  The

The Among things, that they are capable of anticipation. For instance, they show much excitement when I simply touch my car keys, which might well signal that they are going to some place interesting, like the beach. That proves that they have imagination and even memory.

Among things, that they are capable of anticipation. For instance, they show much excitement when I simply touch my car keys, which might well signal that they are going to some place interesting, like the beach. That proves that they have imagination and even memory. The Vatican, Kremlin, and Valhalla of modernism—home of the faith, the sway, and the glamour—that is the Museum of Modern Art is reopening, after an expansion that adds forty-seven thousand square feet and many new galleries, inserted into an apartment tower next door and built on neighboring land gobbled from the late, by some of us lamented, digs of the American Folk Art Museum. Far more, though still a fraction, of moma’s nonpareil collection is now on display, arranged roughly chronologically but studded with such mutually provoking juxtapositions as a 1967 painting that fantasizes a race riot, by the African-American artist Faith Ringgold, with Picasso’s gospel “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907). The renovation is a big deal for the global art world, and certainly for New York. It runs up against problems old and new. Generously enlarged quarters will only marginally relieve a chronic crush of visitors, the museum victimized by its own charisma. Enhanced representations of art by women, African-Americans, Africans, Latin-Americans, and Asians can feel tentative, pitched between self-evident justice and noblesse oblige. But such efforts are important and must continue. We will have a diverse cosmopolitan culture or none worth bothering about.

The Vatican, Kremlin, and Valhalla of modernism—home of the faith, the sway, and the glamour—that is the Museum of Modern Art is reopening, after an expansion that adds forty-seven thousand square feet and many new galleries, inserted into an apartment tower next door and built on neighboring land gobbled from the late, by some of us lamented, digs of the American Folk Art Museum. Far more, though still a fraction, of moma’s nonpareil collection is now on display, arranged roughly chronologically but studded with such mutually provoking juxtapositions as a 1967 painting that fantasizes a race riot, by the African-American artist Faith Ringgold, with Picasso’s gospel “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907). The renovation is a big deal for the global art world, and certainly for New York. It runs up against problems old and new. Generously enlarged quarters will only marginally relieve a chronic crush of visitors, the museum victimized by its own charisma. Enhanced representations of art by women, African-Americans, Africans, Latin-Americans, and Asians can feel tentative, pitched between self-evident justice and noblesse oblige. But such efforts are important and must continue. We will have a diverse cosmopolitan culture or none worth bothering about. The economic appeal of the Trump campaign, and his success in parts of the Midwestern industrial heartland has provoked a rash of explanations and invective centered on the “white working class.” But the “angry white worker” line misses too much. Trump did not grow the GOP base substantially, though he outperformed McCain in 2008 and Romney in 2012 by over 2 million votes. More importantly, Trump did not secure a larger share of the white vote than Romney did. Trump performed well among blue collar voters, former Obama voters, wealthy whites, non-unionized workers in coal country, the steel-producing belt and Right to Work states, building trades and contractors, proto-entrepreneurs, and minorities. One-third of Latino voters supported Trump, as did 13% of African American men.

The economic appeal of the Trump campaign, and his success in parts of the Midwestern industrial heartland has provoked a rash of explanations and invective centered on the “white working class.” But the “angry white worker” line misses too much. Trump did not grow the GOP base substantially, though he outperformed McCain in 2008 and Romney in 2012 by over 2 million votes. More importantly, Trump did not secure a larger share of the white vote than Romney did. Trump performed well among blue collar voters, former Obama voters, wealthy whites, non-unionized workers in coal country, the steel-producing belt and Right to Work states, building trades and contractors, proto-entrepreneurs, and minorities. One-third of Latino voters supported Trump, as did 13% of African American men. I’d never heard the word before. Stillicide,” a corporate executive named Steven thinks to himself around a third of the way through Cynan Jones’s fragmented, marvellously compressed novel of the same title. “Water falling in drops. I challenge myself to get it into a sentence for the [journalists].” I had not heard the word before either, though Jones helpfully opens with a dictionary definition. And it is this image of dripping water and its powers of erosion that comes to define his book as a whole, both as a novel that confronts the challenge of describing what climate crisis might look like, and in the way a slow accretion of pertinent detail gathers cataclysmic momentum.

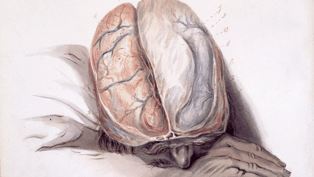

I’d never heard the word before. Stillicide,” a corporate executive named Steven thinks to himself around a third of the way through Cynan Jones’s fragmented, marvellously compressed novel of the same title. “Water falling in drops. I challenge myself to get it into a sentence for the [journalists].” I had not heard the word before either, though Jones helpfully opens with a dictionary definition. And it is this image of dripping water and its powers of erosion that comes to define his book as a whole, both as a novel that confronts the challenge of describing what climate crisis might look like, and in the way a slow accretion of pertinent detail gathers cataclysmic momentum. In wondering what can be done to steer civilization away from the abyss, I confess to being increasingly puzzled by the central enigma of contemporary cognitive psychology: To what degree are we consciously capable of changing our minds? I don’t mean changing our minds as to who is the best NFL quarterback, but changing our convictions about major personal and social issues that should unite but invariably divide us. As a senior neurologist whose career began before CAT and MRI scans, I have come to feel that conscious reasoning, the commonly believed remedy for our social ills, is an illusion, an epiphenomenon supported by age-old mythology rather than convincing scientific evidence. If so, it’s time for us to consider alternate ways of thinking about thinking that are more consistent with what little we do understand about brain function. I’m no apologist for artificial intelligence, but if we are going to solve the world’s greatest problems, there are several major advantages in abandoning the notion of conscious reason in favor of seeing humans as having an AI-like “black-box” intelligence.

In wondering what can be done to steer civilization away from the abyss, I confess to being increasingly puzzled by the central enigma of contemporary cognitive psychology: To what degree are we consciously capable of changing our minds? I don’t mean changing our minds as to who is the best NFL quarterback, but changing our convictions about major personal and social issues that should unite but invariably divide us. As a senior neurologist whose career began before CAT and MRI scans, I have come to feel that conscious reasoning, the commonly believed remedy for our social ills, is an illusion, an epiphenomenon supported by age-old mythology rather than convincing scientific evidence. If so, it’s time for us to consider alternate ways of thinking about thinking that are more consistent with what little we do understand about brain function. I’m no apologist for artificial intelligence, but if we are going to solve the world’s greatest problems, there are several major advantages in abandoning the notion of conscious reason in favor of seeing humans as having an AI-like “black-box” intelligence.

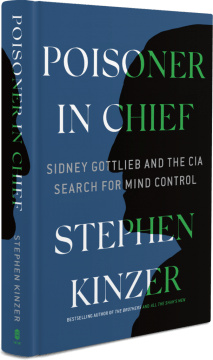

In 1955, R. Gordon Wasson set off for southern Mexico to experience a sacred Indian ceremony rumored to provide a “pathway to the divine.” Wasson later extolled the mystical effects of what he called the “magic mushroom,” the Mexican plant used in the ceremony, in

In 1955, R. Gordon Wasson set off for southern Mexico to experience a sacred Indian ceremony rumored to provide a “pathway to the divine.” Wasson later extolled the mystical effects of what he called the “magic mushroom,” the Mexican plant used in the ceremony, in  Like so many technological innovations, the internet is something that burst on the scene and pervaded human life well before we had time to sit down and think through how something like that should work and how it should be organized. In multiple ways — as a blogger, activist, fiction writer, and more — Cory Doctorow has been thinking about how the internet is affecting our lives since the very beginning. He has been especially interested in legal issues surrounding copyright, publishing, and free speech, and recently his attention has turned to broader economic concerns. We talk about how the internet has become largely organized through just a small number of quasi-monopolistic portals, how this affects the ways in which we gather information and decide whether to trust outside sources, and where things might go from here.

Like so many technological innovations, the internet is something that burst on the scene and pervaded human life well before we had time to sit down and think through how something like that should work and how it should be organized. In multiple ways — as a blogger, activist, fiction writer, and more — Cory Doctorow has been thinking about how the internet is affecting our lives since the very beginning. He has been especially interested in legal issues surrounding copyright, publishing, and free speech, and recently his attention has turned to broader economic concerns. We talk about how the internet has become largely organized through just a small number of quasi-monopolistic portals, how this affects the ways in which we gather information and decide whether to trust outside sources, and where things might go from here. While all men might be equal in death, all sponsors must all be thanked in appropriately sized font. The memorial courtyard now contains an eternal flame, a donation from AGL, Santos and East Australian Pipelines. The gas for the eternal flame is ‘generously’ provided by Origin Energy under a sponsorship agreement. The gas industry’s ‘sacrifice’ in funding a tiny fraction of the local cost of the Australian War Memorial receives far more prominence than the names of Australian who gave their lives for our country. Lest we forget our sponsors. … While the irony of sponsorship by the oil industry, a fuel over which so many wars were fought in the twentieth century, might be missed by some, surely no one could miss the irony of BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin, Thales and other weapons manufacturers sponsoring the Australian War Memorial.

While all men might be equal in death, all sponsors must all be thanked in appropriately sized font. The memorial courtyard now contains an eternal flame, a donation from AGL, Santos and East Australian Pipelines. The gas for the eternal flame is ‘generously’ provided by Origin Energy under a sponsorship agreement. The gas industry’s ‘sacrifice’ in funding a tiny fraction of the local cost of the Australian War Memorial receives far more prominence than the names of Australian who gave their lives for our country. Lest we forget our sponsors. … While the irony of sponsorship by the oil industry, a fuel over which so many wars were fought in the twentieth century, might be missed by some, surely no one could miss the irony of BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin, Thales and other weapons manufacturers sponsoring the Australian War Memorial. But by far the most affecting performance came toward the event’s end, when the lights dimmed and an image of Stritch herself materialized on a big screen, like a glamorous ghost, in what might have been called her prime had she not so forcefully redefined that term. Wearing an ensemble of white blouse and black tights cribbed from Judy Garland’s famous “Get Happy” sequence but carried off even more effectively with her long, slim legs, she began the Sondheim song “The Ladies Who Lunch,” from the landmark 1970 musical Company, which was for so many years her signature anthem.

But by far the most affecting performance came toward the event’s end, when the lights dimmed and an image of Stritch herself materialized on a big screen, like a glamorous ghost, in what might have been called her prime had she not so forcefully redefined that term. Wearing an ensemble of white blouse and black tights cribbed from Judy Garland’s famous “Get Happy” sequence but carried off even more effectively with her long, slim legs, she began the Sondheim song “The Ladies Who Lunch,” from the landmark 1970 musical Company, which was for so many years her signature anthem. The positive lesson was that the most important thing a teacher can convey is a deep love of literature and an understanding that it offers insights, wisdom, and experiences to be found nowhere else. Nothing could be further from Bloom than the usual ways in which most students are taught literature today. Most learn mechanics: let’s find symbols. Others are instructed to see the work as a mere document of its times. And many are taught to summon the author before the stern tribunal of contemporary beliefs so as to measure where she approached modern views and where she fell short. (Bloom was to name such criticism “the school of resentment.”) Each of these approaches places the critic in a position superior to great works, which makes it hard to see why it is worth the effort to read them. Bloom instructed us to do the opposite: presume that the poets are wiser than we are so we can immerse ourselves in their works and share in their insights. Then the considerable difficulty of reading Milton or Spencer or Shelley makes sense.

The positive lesson was that the most important thing a teacher can convey is a deep love of literature and an understanding that it offers insights, wisdom, and experiences to be found nowhere else. Nothing could be further from Bloom than the usual ways in which most students are taught literature today. Most learn mechanics: let’s find symbols. Others are instructed to see the work as a mere document of its times. And many are taught to summon the author before the stern tribunal of contemporary beliefs so as to measure where she approached modern views and where she fell short. (Bloom was to name such criticism “the school of resentment.”) Each of these approaches places the critic in a position superior to great works, which makes it hard to see why it is worth the effort to read them. Bloom instructed us to do the opposite: presume that the poets are wiser than we are so we can immerse ourselves in their works and share in their insights. Then the considerable difficulty of reading Milton or Spencer or Shelley makes sense. The landscape of Lessing’s childhood – and her sense of being in exile from it afterwards – remained, I think, the key to her writing in the 40 books that eventually gained her a Nobel Prize. Her experience of the veld was crucial to her politics. She became a communist because she was outraged by the system of racial segregation known as the colour bar, oppressing the black people she heard playing the drums at night outside in the bush while her mother played Chopin on the piano. And the veld was also crucial to her life as a feminist. After roaming freely as a child, sometimes pausing to shoot guinea fowl, she didn’t understand the conventions governing women’s lives in the city. Living in the Southern Rhodesian capital of Salisbury (now Harare), she found the nuclear family unbearably claustrophobic and longed to escape a social world that restricted the independence of women. And so, in 1942, aged 23, she abandoned her marriage, leaving behind two children.

The landscape of Lessing’s childhood – and her sense of being in exile from it afterwards – remained, I think, the key to her writing in the 40 books that eventually gained her a Nobel Prize. Her experience of the veld was crucial to her politics. She became a communist because she was outraged by the system of racial segregation known as the colour bar, oppressing the black people she heard playing the drums at night outside in the bush while her mother played Chopin on the piano. And the veld was also crucial to her life as a feminist. After roaming freely as a child, sometimes pausing to shoot guinea fowl, she didn’t understand the conventions governing women’s lives in the city. Living in the Southern Rhodesian capital of Salisbury (now Harare), she found the nuclear family unbearably claustrophobic and longed to escape a social world that restricted the independence of women. And so, in 1942, aged 23, she abandoned her marriage, leaving behind two children.