Catherine Fletcher at Literary Review:

Just as problematic for ‘God’s architect’ was the question of his private life. Although Wallace’s primary focus is on Michelangelo at work, he paints a picture too of the artist at home, whether at prayer, corresponding with family members or enduring the pain of kidney stones. His was not the archetypal household of its time and place: Michelangelo was unmarried and did not live with blood relatives. Nor does it fit the model of the characteristic male-dominated ecclesiastical house in Rome, for the simple reason that Michelangelo was not a cleric. There was, in fact, a great deal of the ‘found family’ about it: a motley bunch of ‘housemates’ (Wallace’s term) shared the same space, in some cases with their spouses, sometimes for business convenience, sometimes for more personal reasons.

Just as problematic for ‘God’s architect’ was the question of his private life. Although Wallace’s primary focus is on Michelangelo at work, he paints a picture too of the artist at home, whether at prayer, corresponding with family members or enduring the pain of kidney stones. His was not the archetypal household of its time and place: Michelangelo was unmarried and did not live with blood relatives. Nor does it fit the model of the characteristic male-dominated ecclesiastical house in Rome, for the simple reason that Michelangelo was not a cleric. There was, in fact, a great deal of the ‘found family’ about it: a motley bunch of ‘housemates’ (Wallace’s term) shared the same space, in some cases with their spouses, sometimes for business convenience, sometimes for more personal reasons.

Thanks to Gary Ferguson’s recent account of Renaissance Rome’s queer subculture, we now have more information with which to flesh out the might-have-beens of same-sex relationships at that time. But while elsewhere in the book Wallace is happy to fill in historical gaps with speculation, he opts for studied ambiguity when it comes to the precise nature of Michelangelo’s friendships with other men.

more here.

Shortly after I met my wife, Cindy, in 1989—she was living in New York City at the time, while I was living in Northern Virginia—she told me about a new church she was attending in Manhattan:

Shortly after I met my wife, Cindy, in 1989—she was living in New York City at the time, while I was living in Northern Virginia—she told me about a new church she was attending in Manhattan:  Ross Goodwin has had an extraordinary career. After playing about with computers as a child, he studied economics, then became a speech writer for President Obama, writing presidential proclamations, then took a variety of freelance writing jobs. One of these involved churning out business letters—he calls it freelance ghostwriting. The letters were all pretty much the same, so he figured out an algorithm that would generate form letters, using a few samples as a database. The algorithm jumbled up paragraphs and lines following certain templates, then reassembled them to produce business letters, similar but each varying in style, saving him the job of starting anew each time. He thought he was on to something new but soon found out that this was a well-explored area. But it did pique his interest in the “intersection of writing and computation.”

Ross Goodwin has had an extraordinary career. After playing about with computers as a child, he studied economics, then became a speech writer for President Obama, writing presidential proclamations, then took a variety of freelance writing jobs. One of these involved churning out business letters—he calls it freelance ghostwriting. The letters were all pretty much the same, so he figured out an algorithm that would generate form letters, using a few samples as a database. The algorithm jumbled up paragraphs and lines following certain templates, then reassembled them to produce business letters, similar but each varying in style, saving him the job of starting anew each time. He thought he was on to something new but soon found out that this was a well-explored area. But it did pique his interest in the “intersection of writing and computation.” It is a truth, though sadly not one universally acknowledged, that what you think of religion largely depends on what you think is religion. If you believe religion to be primarily a means of explaining the origins and processes of the world and of nature, you’ll measure it with a scientific yardstick and find it wanting. If you think it is a metaphysical enterprise, making propositional but untestable statements about human identity and destiny, you’ll assess it on more philosophical principles, and find it momentous or meaningless depending on whether you like your ideas falsifiable. If you think it’s a series of ethical guidelines for how to navigate the world, with little truth content in themselves, you’ll measure it on a moral scale, and find it inspiring or dispiriting, depending on which bits you’re looking at. And so on and so forth.

It is a truth, though sadly not one universally acknowledged, that what you think of religion largely depends on what you think is religion. If you believe religion to be primarily a means of explaining the origins and processes of the world and of nature, you’ll measure it with a scientific yardstick and find it wanting. If you think it is a metaphysical enterprise, making propositional but untestable statements about human identity and destiny, you’ll assess it on more philosophical principles, and find it momentous or meaningless depending on whether you like your ideas falsifiable. If you think it’s a series of ethical guidelines for how to navigate the world, with little truth content in themselves, you’ll measure it on a moral scale, and find it inspiring or dispiriting, depending on which bits you’re looking at. And so on and so forth. Standing in

Standing in

W

W On display at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan—amid the lacquered black metal of Model Ts and the hanging flanks of the first planes to fly over the poles, just feet from Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House and the bus seat made famous by Rosa Parks, mere yards from the chair in which Abraham Lincoln was shot and the limousine in which John Fitzgerald Kennedy was also, yes, shot—is a small, clear, and seemingly empty test tube, once rumored to contain the last breath of Thomas Edison.

On display at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan—amid the lacquered black metal of Model Ts and the hanging flanks of the first planes to fly over the poles, just feet from Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House and the bus seat made famous by Rosa Parks, mere yards from the chair in which Abraham Lincoln was shot and the limousine in which John Fitzgerald Kennedy was also, yes, shot—is a small, clear, and seemingly empty test tube, once rumored to contain the last breath of Thomas Edison. This goes to the center of it. Until the election of Donald Trump, the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? was titled The Radical Mister Rogers. The filmmaker (owing much to Long’s book) realized that billing “would turn off people who needed to see it.” Joanne told me the premiere at Sundance was attended by cross-party politicians; in fact, she’d heard it “pleased both sides.” In the outright sense, she allowed, Rogers did not behave politically. “Many parents wouldn’t have let their kids watch.” (The national broadcast of Neighborhood was sponsored by the Sears-Roebuck Foundation, and “Sears would not have wanted to lose people.”) “But if both sides were pleased with the doc,” held Long, “either one side wasn’t paying close attention or its treatment of Rogers’s leftist politics was insufficient.”

This goes to the center of it. Until the election of Donald Trump, the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? was titled The Radical Mister Rogers. The filmmaker (owing much to Long’s book) realized that billing “would turn off people who needed to see it.” Joanne told me the premiere at Sundance was attended by cross-party politicians; in fact, she’d heard it “pleased both sides.” In the outright sense, she allowed, Rogers did not behave politically. “Many parents wouldn’t have let their kids watch.” (The national broadcast of Neighborhood was sponsored by the Sears-Roebuck Foundation, and “Sears would not have wanted to lose people.”) “But if both sides were pleased with the doc,” held Long, “either one side wasn’t paying close attention or its treatment of Rogers’s leftist politics was insufficient.” Brian is telling a young Asian-American woman about the five-day workshop he’s here to attend. “It’s called ‘Bio-hacking the Language of Intimacy’,” he says. “Uh-huh,” says the Asian-American woman. She directs this less at Brian than at the kelp forest floating offshore. Brian presses on. What he particularly appreciates is the ability to talk about stuff he can’t talk about at work. Relationships and so forth. “You know,” he says, “really make that human connection.” The Asian-American woman gives him the sort of bright, dead-eyed smile Californians deploy when they’re about to violently disagree with you. “I find I can make human connections in lots of different contexts.” Brian goes quiet. In all but one sense it’s a typically, even touchingly American courtship ritual: the clean-cut young man, no less diffident nor deferential than his grandfather might have been; the young woman off-handedly wielding her power over him, yet to be impressed. The crucial difference is that both parties are naked – not only naked, in the woman’s case, but standing up in the water, exposing herself in full-frontal immodesty to Brian and the cool Pacific breezes. We are in the outdoor sulphur springs that cling to the cliffside at the Esalen Institute, a spiritual retreat centre in Big Sur, California. Here naked sharing is commonplace and as sapped of erotic charge as it would be in a naturist campsite – which is just as well, as I’m naked too, the gooseberry in the hot tub, desperately aiming for an air of easygoing self-composure as I try not to look at Brian’s thighs.

Brian is telling a young Asian-American woman about the five-day workshop he’s here to attend. “It’s called ‘Bio-hacking the Language of Intimacy’,” he says. “Uh-huh,” says the Asian-American woman. She directs this less at Brian than at the kelp forest floating offshore. Brian presses on. What he particularly appreciates is the ability to talk about stuff he can’t talk about at work. Relationships and so forth. “You know,” he says, “really make that human connection.” The Asian-American woman gives him the sort of bright, dead-eyed smile Californians deploy when they’re about to violently disagree with you. “I find I can make human connections in lots of different contexts.” Brian goes quiet. In all but one sense it’s a typically, even touchingly American courtship ritual: the clean-cut young man, no less diffident nor deferential than his grandfather might have been; the young woman off-handedly wielding her power over him, yet to be impressed. The crucial difference is that both parties are naked – not only naked, in the woman’s case, but standing up in the water, exposing herself in full-frontal immodesty to Brian and the cool Pacific breezes. We are in the outdoor sulphur springs that cling to the cliffside at the Esalen Institute, a spiritual retreat centre in Big Sur, California. Here naked sharing is commonplace and as sapped of erotic charge as it would be in a naturist campsite – which is just as well, as I’m naked too, the gooseberry in the hot tub, desperately aiming for an air of easygoing self-composure as I try not to look at Brian’s thighs. For more than 25 years one idea has dominated scientific thinking about Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. It holds that the disorder, which afflicts about one in 10 Americans age 65 or older, is caused by a buildup in the brain of abnormal amyloid-beta protein, which eventually destroys neurons and synapses, producing the tragic symptoms of dementia. There’s plenty of evidence for this. First, the presence of sticky clumps or “plaques” containing amyloid is a classic hallmark of the disease (along with tangles of a protein called tau). It was what

For more than 25 years one idea has dominated scientific thinking about Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. It holds that the disorder, which afflicts about one in 10 Americans age 65 or older, is caused by a buildup in the brain of abnormal amyloid-beta protein, which eventually destroys neurons and synapses, producing the tragic symptoms of dementia. There’s plenty of evidence for this. First, the presence of sticky clumps or “plaques” containing amyloid is a classic hallmark of the disease (along with tangles of a protein called tau). It was what  The idea that we have evolved to see reality ‘as it is’ is commonplace. While it might seem irresponsible, in this age of ‘fake news’ and ubiquitous political and commercial propaganda, to argue that we are not evolved to see reality as it is, I believe it’s worth doing, not least for what it reveals about our notions of ‘reality’ and ‘evolution’.

The idea that we have evolved to see reality ‘as it is’ is commonplace. While it might seem irresponsible, in this age of ‘fake news’ and ubiquitous political and commercial propaganda, to argue that we are not evolved to see reality as it is, I believe it’s worth doing, not least for what it reveals about our notions of ‘reality’ and ‘evolution’. We’ve talked a lot recently about the Many Worlds of quantum mechanics. That’s one kind of multiverse that physicists often contemplate. There is also the cosmological multiverse, which we talked about with Brian Greene. Today’s guest, Max Tegmark, has thought a great deal about both of those ideas, as well as a more ambitious and speculative one: the Mathematical Multiverse, in which we imagine that every mathematical structure is real, and the universe we perceive is just one such mathematical structure. And there’s yet another possibility, that what we experience as “reality” is just a simulation inside computers operated by some advanced civilization. Max has thought about all of these possibilities at a deep level, as his research has ranged from physical cosmology to foundations of quantum mechanics and now to applied artificial intelligence. Strap in and be ready for a wild ride.

We’ve talked a lot recently about the Many Worlds of quantum mechanics. That’s one kind of multiverse that physicists often contemplate. There is also the cosmological multiverse, which we talked about with Brian Greene. Today’s guest, Max Tegmark, has thought a great deal about both of those ideas, as well as a more ambitious and speculative one: the Mathematical Multiverse, in which we imagine that every mathematical structure is real, and the universe we perceive is just one such mathematical structure. And there’s yet another possibility, that what we experience as “reality” is just a simulation inside computers operated by some advanced civilization. Max has thought about all of these possibilities at a deep level, as his research has ranged from physical cosmology to foundations of quantum mechanics and now to applied artificial intelligence. Strap in and be ready for a wild ride. Impeachment has a way of bringing out a president’s worst instincts — and the world could end up paying the price.

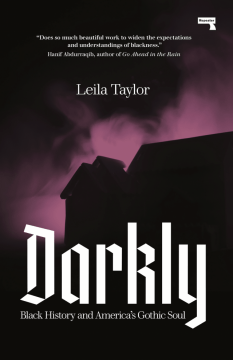

Impeachment has a way of bringing out a president’s worst instincts — and the world could end up paying the price. In Darkly, Leila Taylor offers a racially-minded revision of the Gothic canon, from Walpole to the present, with a particular focus on its American incarnations. But two things make this compendium a vital addition to the existing commentary. First is the fact that Taylor is no reductionist, and isn’t tempted, say, to dismiss the entire Gothic canon as irredeemably racist. Instead, Darkly makes a compelling and subtle argument: on the one hand, that the American Gothic is not simply a transplanting of an inherently European aesthetic, but a symptom of America’s (ongoing) legacy of racial oppression; on the other, that the American Gothic also promises a cure, a means of resisting that very oppression — that by allowing ourselves to be haunted by its texts, we can hope to terminate the legacy which produced them. Second is Taylor’s unapologetic use of the first person, her extensive reference to her subjective experience. That experience is directly related to the book’s argument: as Darkly makes clear, the legacy of racial oppression in America is something which Taylor has encountered — and continues to encounter — on a daily basis. But the inclusion of Taylor’s “I” here lends more than, say, credibility to her case (that case is already so tight, it would stand irrespective of who made it); it also ensures that Darkly, like the 43rd Capricho, is a self-portrait. By discussing how it feels for her to watch, say, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead — with its appropriations of Haitian folklore, and with the indiscriminate slaughter of the Black protagonist in its final scenes — Taylor forces us to participate in her experience. Darkly, then, to paraphrase something that Beckett once said of Joyce, is not just about the uncanny, it is uncanny.

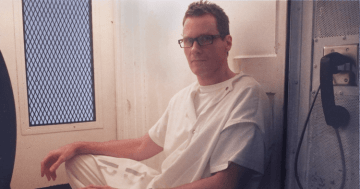

In Darkly, Leila Taylor offers a racially-minded revision of the Gothic canon, from Walpole to the present, with a particular focus on its American incarnations. But two things make this compendium a vital addition to the existing commentary. First is the fact that Taylor is no reductionist, and isn’t tempted, say, to dismiss the entire Gothic canon as irredeemably racist. Instead, Darkly makes a compelling and subtle argument: on the one hand, that the American Gothic is not simply a transplanting of an inherently European aesthetic, but a symptom of America’s (ongoing) legacy of racial oppression; on the other, that the American Gothic also promises a cure, a means of resisting that very oppression — that by allowing ourselves to be haunted by its texts, we can hope to terminate the legacy which produced them. Second is Taylor’s unapologetic use of the first person, her extensive reference to her subjective experience. That experience is directly related to the book’s argument: as Darkly makes clear, the legacy of racial oppression in America is something which Taylor has encountered — and continues to encounter — on a daily basis. But the inclusion of Taylor’s “I” here lends more than, say, credibility to her case (that case is already so tight, it would stand irrespective of who made it); it also ensures that Darkly, like the 43rd Capricho, is a self-portrait. By discussing how it feels for her to watch, say, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead — with its appropriations of Haitian folklore, and with the indiscriminate slaughter of the Black protagonist in its final scenes — Taylor forces us to participate in her experience. Darkly, then, to paraphrase something that Beckett once said of Joyce, is not just about the uncanny, it is uncanny. Last June, I interviewed Wardlow at a maximum-security prison called the Polunsky Unit, located 80 miles northeast of Houston, where he is waiting for his execution on death row. He has been incarcerated for a quarter of a century, but the state has now set a date for his death: April 29, 2020. His lawyers, Richard Burr and Mandy Welch, having gotten to know him well in the 23 years that they have represented him, told me they are convinced that time has shown the jury to have been wrong in determining Wardlow posed a future danger. The more I have read about his case and his life, the more I think they are right. Wardlow stands out as someone the legal system has wronged repeatedly, especially in deciding his punishment.

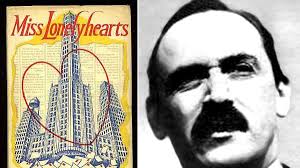

Last June, I interviewed Wardlow at a maximum-security prison called the Polunsky Unit, located 80 miles northeast of Houston, where he is waiting for his execution on death row. He has been incarcerated for a quarter of a century, but the state has now set a date for his death: April 29, 2020. His lawyers, Richard Burr and Mandy Welch, having gotten to know him well in the 23 years that they have represented him, told me they are convinced that time has shown the jury to have been wrong in determining Wardlow posed a future danger. The more I have read about his case and his life, the more I think they are right. Wardlow stands out as someone the legal system has wronged repeatedly, especially in deciding his punishment. It was at this point I discovered Nathanael West. Although all his books had been published in the 1930s, they seemed to anticipate the America that was throbbing all around me, with its violence and disappointments, its spiritual emptiness, its foolishness and its freaks.

It was at this point I discovered Nathanael West. Although all his books had been published in the 1930s, they seemed to anticipate the America that was throbbing all around me, with its violence and disappointments, its spiritual emptiness, its foolishness and its freaks.