[From Boing Boing.]

Category: Recommended Reading

Meeting a prodigious memory

Stafan Zweig (writing in 1929, Vienna) in Lapham’s Quarterly:

I reiterated my object in consulting him: to get a list of all the early works on animal magnetism, and of contemporary and subsequent books and pamphlets for and against Mesmer. When I had said my say, Mendel closed his left eye for an instant, as if excluding a grain of dust. This was, with him, a sign of concentrated attention. Then, as though reading from an invisible catalogue, he reeled out the names of two or three dozen titles, giving in each case place and date of publication and approximate price. I was amazed, though Schmidt had warned me what to expect. His vanity was tickled by my surprise, for he went on to strum the keyboard of his marvelous memory, and to produce the most astounding bibliographic marginal notes. Did I want to know about sleepwalkers, Perkins’ metallic tractors, early experiments in hypnotism, Braid, Gassner, attempts to conjure up the devil, Christian Science, theosophy, Madame Blavatsky? In connection with each item, there was a hailstorm of book names, dates, and appropriate details. I was beginning to understand that Jacob Mendel was a living lexicon, something like the general catalogue of the British Museum Reading Room, but able to walk about on two legs.

…True, this memory owed its infallibility to the man’s limitations, to his extraordinary power of concentration. Apart from books, he knew nothing of the world. The phenomena of existence did not begin to become real for him until they had been set in type, arranged upon a composing stick, collected, and, so to say, sterilized in a book. Nor did he read books for their meaning, to extract their spiritual or narrative substance. What aroused his passionate interest, what fixed his attention, was the name, the price, the format, the title page. Though in the last analysis unproductive and uncreative, this specifically antiquarian memory of Jacob Mendel, since it was not a printed book catalogue but was stamped upon the gray matter of a mammalian brain, was, in its unique perfection, no less remarkable a phenomenon than Napoleon’s gift for physiognomy, Mezzofanti’s talent for languages, Lasker’s skill at chess openings, Busoni’s musical genius. When someday there arises a great psychologist who shall classify the types of that magical power we term memory as effectively as Buffon classified the genera and species of animals, a man competent to give a detailed description of all the varieties, he will have to find a pigeonhole for Jacob Mendel, forgotten master of the lore of book prices and book titles, the ambulatory catalogue alike of incunabula and the modern commonplace.

More here.

London Falling: The dying empire state of mind

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

IT IS A TRUTH universally accepted that any columnist who travels to a foreign country to write will be, eventually, in search of a cab. If the entire Middle East has been made intelligible to New York Times readers by the inveterate interviewer of taxi drivers Thomas Friedman, then so too with the fate of Near-Brexit Britain. It follows that when I got to London on Election Day (December 12) I immediately got into the taxi line at Heathrow airport. Soon, I figured, an insightful and expert cab driver who I would dub Niles or Julian in my ensuing column, would deliver me the gems that make for good punditry. It was, predictably, a rainy and blustery day in London, and I scurried to the cab to which I had been pointed as fast as I could. The driver, however, was not so inclined; not, in fact, inclined at all. A white man, he sat in his black cab and looked straight ahead. I kept banging at the door until finally the attendant sidled over and said “Take the next one.” I did and as I did, I saw from the corner of my eye a white woman who had stood behind me in line get into the cab that had been unavailable to me. The cab driver so immoveable to my entreaties readily got out and loaded her suitcases for her.

IT IS A TRUTH universally accepted that any columnist who travels to a foreign country to write will be, eventually, in search of a cab. If the entire Middle East has been made intelligible to New York Times readers by the inveterate interviewer of taxi drivers Thomas Friedman, then so too with the fate of Near-Brexit Britain. It follows that when I got to London on Election Day (December 12) I immediately got into the taxi line at Heathrow airport. Soon, I figured, an insightful and expert cab driver who I would dub Niles or Julian in my ensuing column, would deliver me the gems that make for good punditry. It was, predictably, a rainy and blustery day in London, and I scurried to the cab to which I had been pointed as fast as I could. The driver, however, was not so inclined; not, in fact, inclined at all. A white man, he sat in his black cab and looked straight ahead. I kept banging at the door until finally the attendant sidled over and said “Take the next one.” I did and as I did, I saw from the corner of my eye a white woman who had stood behind me in line get into the cab that had been unavailable to me. The cab driver so immoveable to my entreaties readily got out and loaded her suitcases for her.

I did get into the next cab, whose driver, thankfully, was an elderly Jamaican-British man. Then it sunk in: I was a brown person in London on a day when there was a reckoning, in some significant part, on the acceptability of brown and black others. My new cab-driver expert affirmed this. “It’s all about the immigrants,” he said as the cab sped past surly London suburbs, rain soaked and wan. “All the jobs here are done by the immigrants but the British don’t want us,” he expounded. “Get rid of the immigrants they say,” he went on as we slipped under a graffiti-sprayed bridge; in the whorls and words I could read an angrily scrawled “Out.” When we got to my budget hotel my cab driver sent me off with “Boris Johnson is going to win.”

Boris Johnson did win and the results were as anti-climactic as election results can be.

More here.

Sunday Poem

An iPoem

You must hold your quiet center,

where you do what only you can do.

If others call you a maniac or a fool,

just let them wag their tongues.

If some praise your perseverance,

don’t feel too happy about it—

only solitude is your lasting friend.

You must hold your distant center.

Don’t move even if earth and heaven quake.

If others think you are insignificant,

that’s because you haven’t held on long enough.

As long as you stay put year after year,

someday you will find a world

beginning to revolve around you.

by by Ha Jin

from The Distant Center

Copper Canyon Press, 2018

Saturday, December 28, 2019

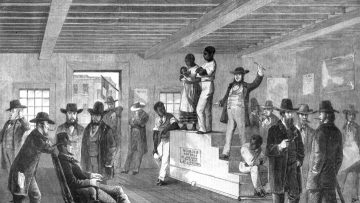

The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts

Adam Serwer in The Atlantic:

U.S. history is often taught and popularly understood through the eyes of its great men, who are seen as either heroic or tragic figures in a global struggle for human freedom. The 1619 Project, named for the date of the first arrival of Africans on American soil, sought to place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Viewed from the perspective of those historically denied the rights enumerated in America’s founding documents, the story of the country’s great men necessarily looks very different.

The reaction to the project was not universally enthusiastic. Several weeks ago, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, who had criticized the 1619 Project’s “cynicism” in a lecture in November, began quietly circulating a letter objecting to the project, and some of Hannah-Jones’s work in particular. The letter acquired four signatories—James McPherson, Gordon Wood, Victoria Bynum, and James Oakes, all leading scholars in their field. They sent their letter to three top Times editors and the publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, on December 4. A version of that letter was published on Friday, along with a detailed rebuttal from Jake Silverstein, the editor of the Times Magazine.

More here.

The Democratic People’s Republic of U.S. Monetary Policy

Leah Downey in Foreign Policy:

In a post-Great Recession world, monetary policy just looks different. For one thing, central bank independence is dead—but the U.S. Congress doesn’t know it yet. We could argue for hours, or days, about whether it ever really existed or when exactly it died, but suffice to say that the moment quantitative easing started, the Federal Reserve stepped out of its well-defined monetary box, and independence was no more. Central bankers know it: In a recent survey, 61 percent of former central bankers surveyed from around the world predicted that central banks would be less independent in the future.

The U.S. Congress has not acknowledged this reality. Members of Congress depend on the doctrine of central bank independence to keep the dirty business of monetary policy off their hands. The question is whether Congress will continue to ignore reality and let the Fed take on more power—and increasingly fiscal rather than just monetary—over the economy or whether it will choose to step in, reassert its political power, and get more involved. Most important of all is a question no one seems willing to ask: What might the answer to this question say about the state of U.S. democracy?

More here.

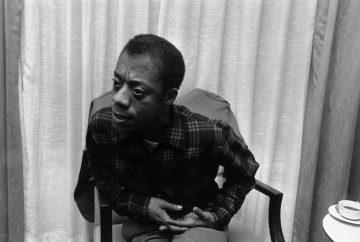

The Radical James Baldwin

Laura Tanenbaum in Jacobin:

Laura Tanenbaum in Jacobin:

Living in Fire, Bill Mullen’s new biography of James Baldwin is many things: a short, accessible introduction to Baldwin’s life and work drawing on his letters and unpublished writings; an argument for his place among left artists and writers; and an overview of his less well-known writings on queer identity and anti-imperialism, including their relation to Palestine. It’s also a great advertisement for the New York City public schools.

Baldwin grew up as the oldest of nine children. His father was a storefront preacher who worked at a soda bottling plant, making $27.50 a week. His childhood took place largely during the Great Depression, when black unemployment reached 50 percent, but Baldwin’s teacher, Orilla Miller, nonetheless called the poverty of Baldwin’s house among the worst she had seen. Taking a liking to Baldwin, Miller brought him along to the movies, an experience he would recount many years later in The Devil Finds Work, his book-length essay about American films; her husband took Baldwin to the May Day parade, where he got his first taste of what he later described as “the universal and inevitable ferment which explodes into what is called a revolution.”

More here.

We Are Witnessing a Rediscovery of India’s Republic

Rohit De and Surabhi Ranganathan in NYT:

Rohit De and Surabhi Ranganathan in NYT:

As India’s new citizenship law seeks to create a stratified citizenship based on religion, a large number of Indians opposing it are emerging as a people of one book, the country’s Constitution, which came into force on Jan. 26, 1950.

In the past two weeks, diverse crowds across the country have responded to the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act, referred to as the C.A.A., passed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government by chanting the preamble to the Constitution of India, with its promises of social, political and economic justice, freedom of thought, expression and belief, equality and fraternity.

Student protesters being herded into police vans, opposition leaders standing outside the Indian Parliament and ebullient crowds of tens of thousands in Hyderabad, Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai and Chennai have read aloud the preamble and held aloft copies of the Constitution and portraits of B.R. Ambedkar, its chief draftsman.

The C.A.A. offers an accelerated pathway to citizenship for Hindu, Sikh, Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Christian migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan but excludes Muslims. It effectively creates a hierarchical system of citizenship determined by an individual’s religion, reminiscent of Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law, which privileged citizenship for “indigenous races,” excluded the Rohingya and paved the ground for the genocidal violence against them.

What It Would Take for Evangelicals to Turn on President Trump

Michael Luo in The New Yorker:

One night in 1953, the Reverend Billy Graham awoke at two in the morning, went to his study, and started writing down ideas for the creation of a new religious journal. Graham, then in his mid-thirties, was an internationally renowned evangelist who held revival meetings that were attended by tens of thousands, in stadiums around the world. He had also become the leader of a cohort of pastors, theologians, and other Protestant luminaries who aspired to create a new Christian movement in the United States that avoided the cultural separatism of fundamentalism and the theological liberalism of mainline Protestantism. Harold Ockenga, a prominent minister and another key figure in the movement, called this more culturally engaged vision of conservative Christianity “new evangelicalism.” Graham believed a serious periodical could serve as the flagship for the movement. The idea for the publication, as he later wrote, was to “plant the Evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems.” The magazine would be called Christianity Today.

One night in 1953, the Reverend Billy Graham awoke at two in the morning, went to his study, and started writing down ideas for the creation of a new religious journal. Graham, then in his mid-thirties, was an internationally renowned evangelist who held revival meetings that were attended by tens of thousands, in stadiums around the world. He had also become the leader of a cohort of pastors, theologians, and other Protestant luminaries who aspired to create a new Christian movement in the United States that avoided the cultural separatism of fundamentalism and the theological liberalism of mainline Protestantism. Harold Ockenga, a prominent minister and another key figure in the movement, called this more culturally engaged vision of conservative Christianity “new evangelicalism.” Graham believed a serious periodical could serve as the flagship for the movement. The idea for the publication, as he later wrote, was to “plant the Evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems.” The magazine would be called Christianity Today.

During the next several decades, Graham’s movement became the dominant force in American religious life, and perhaps the country’s most influential political faction. From the late nineteen-seventies through the mid-eighties, evangelicals became increasingly aligned with the Republican Party, progressively shifting its priorities to culture-war issues like abortion. Today, evangelical Protestants account for approximately a quarter of the U.S. population and represent the political base of the G.O.P. Despite President Trump’s much publicized moral shortcomings, more than eighty per cent of evangelicals supported him in the 2016 election. Last week, however, Mark Galli, the ninth editor to lead Christianity Today since its founding, in 1956, published an editorial calling for President Trump’s impeachment and removal from office. “The president of the United States attempted to use his political power to coerce a foreign leader to harass and discredit one of the president’s political opponents,” Galli writes. “That is not only a violation of the Constitution; more importantly, it is profoundly immoral.” Galli, who will retire from his post early in the new year, implores evangelicals who continue to stand by Trump to “remember who you are and whom you serve. Consider how your justification of Mr. Trump influences your witness to your Lord and Savior.”

Galli and other contributors to the magazine have been critical of Trump in the past, but the forcefulness of the editorial took many by surprise. The piece became a sensation, trending online and receiving widespread media coverage.

More here.

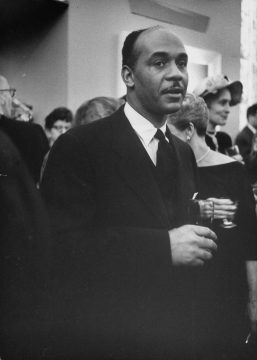

Ralph Ellison’s Letters Reveal a Complex Philosopher of Black Expression

Saidiya Hartman in The New York Times:

“Complexity” was the term that Ralph Ellison deployed most often to describe black life and culture. And it is the term best suited to convey the character of this brilliant, often disapproving and unsparing man. Decades before Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “Song of Solomon,” “Invisible Man” (1952) singularly defined the meaning of literary achievement. As a critic, Ellison was no less significant a thinker and stylist. Always, he was a philosopher of black expressive form and an astute cultural analyst.

“Complexity” was the term that Ralph Ellison deployed most often to describe black life and culture. And it is the term best suited to convey the character of this brilliant, often disapproving and unsparing man. Decades before Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “Song of Solomon,” “Invisible Man” (1952) singularly defined the meaning of literary achievement. As a critic, Ellison was no less significant a thinker and stylist. Always, he was a philosopher of black expressive form and an astute cultural analyst.

I first encountered Ellison through the scrim of Larry Neal’s 1970 essay “Ellison’s Zoot Suit,” so I knew what I needed to read for — the invaluable critical propositions about African-American culture, the dazzling enactment of blues vernacular in modernist prose, artistic achievement steeped in reference to the music and an eye capable of discerning what Zora Neale Hurston described as the distinctive asymmetry and angularity that were the most striking manifestations of black style and the will to adorn. I also knew what I had to read past — the cult of the masculine hero and an aesthetic project that “restores to man his full complexity” and to the native son truth and revelation, while abandoning the daughter to the chaos of the underworld.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Moribund

The animals are dying.

All the beautiful women are dying too.

mass extinction unraveling in your own backyard.

I watch as an unraveling of women

to dry their skin. This must be the most

as a diorama of themselves. In a 1969 lecture available

shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand

her paper

on bacterial pointillism, a type of painting technique whereby mud

field of living pigments, a Rothko-like landscape whose subject is

scientists call

the background rate of extinction, that little death hum of

one to five

a thousand to ten thousand times that. They’re dying

fourteen stories, 196 stories, 2,744 stories, and the women in

the pool

Syrian women haul bundled children through Aleppo’s

Syrian mothers write appeals followed by farewells

no one is helping us in this world, no one is evacuating me &

my daughter,

binding to hemoglobin as a blue thing exposed

posts

a video of a twenty-seven-year-old Muslim woman in Kabul

accused of burning

poles &

bricks are held above her. Then, at a certain velocity, lowered

as she whimpers Allahu Akbar from the ground. I watch this video

between my father’s hands. They kill her. They run

She was never burning a Quran, anyone could’ve seen that.

the specificities blurred by now, I type into the search bar

Only midway through the video do I realize

with a red scarf. In fact, by the time the men get to burning her,

to light her. But those halving miracles

going extinct against the stone wall on the riverbank—

the policemen said, Be careful of the fire.

.

by Hannah Perrin King

from Narrative Magazine

Friday, December 27, 2019

Ila Kumar, 16-year-old, on what she would want her future self to know, after throwing up in her father’s Honda

Ila Kumar, deserving winner of a national writing contest for this, in The Lily:

Dear imagined future self,

Dear imagined future self,

On Halloween, my best friend’s older brother sold us each one Poland Spring water bottle filled with watered-down vodka. There are now 15 dollars less to my name. We drank this vodka with a great deal of teenage bravado — trying not wince at the clear liquid’s resemblance to rubbing alcohol. My friend’s father made a crudité platter for us. The night ended with me throwing up baby carrots and mini peppers in my dad’s Honda, at the first hard left out of my friend’s driveway. Never have I felt more like a 16-year-old.

Future self, I hope you are more sophisticated now. Not a “blousy” adult who wears long necklaces — but the kind of adult who seems like they drink salads, wear camel coats and know the definition to words like “palaver.”

My dad didn’t say anything. I knew he understood what had happened, and why. Maybe the same thing had happened to him when he was 16. Silence hung between us like fog; I felt embarrassed to be alive.

More here.

Can an AI Fact-Checker Solve India’s Fake News Problem?

Puja Changoiwala in Undark:

False words, phony videos, doctored photos, and violent content are regular features on the online ecosystem worldwide. India is no exception, where such content, which often attracts millions of views, has led to grave crimes and even communal and political unrest.

False words, phony videos, doctored photos, and violent content are regular features on the online ecosystem worldwide. India is no exception, where such content, which often attracts millions of views, has led to grave crimes and even communal and political unrest.

With more than half a billion Indians online, the Indian government and social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp now struggle to contain the misinformation and disinformation epidemics. MetaFact, a local startup, says it has found solutions in a type of artificial intelligence called natural language processing, which combines linguistics and computer science. The goal of the technology is to teach computers how to understand how human, or natural, language works by showing it many examples.

MetaFact’s fact-checking tool, the company says, uses natural language processing, sometimes called NLP, to help detect, monitor, and counter phony stories. The tool is meant to extend to newsrooms “the power to detect and monitor fake news in real time, sifting through all the data cacophony that is generated online,” Sagar Kaul, MetaFact’s founder, wrote in an email to Undark.

More here.

Researchers asked 2,500 Jewish and Muslim people what they find offensive – here’s what they said

Julian Hargreaves in The Conversation:

Accusations of antisemitism have been swirling around the Labour Party since Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader in 2015. He has been accused of harbouring antisemitic views and offering public support to party colleagues labelled as antisemitic. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party have faced accusations of “endemic” Islamophobia.

Accusations of antisemitism have been swirling around the Labour Party since Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader in 2015. He has been accused of harbouring antisemitic views and offering public support to party colleagues labelled as antisemitic. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party have faced accusations of “endemic” Islamophobia.

In the run-up to the 2019 general election, the main political parties have repeatedly accused each other of antisemitism and Islamophobia. Away from politics, there are widespread concerns about prejudice targeting Jews and Muslims. But the narratives are often simplistic and without supporting data. We hear much from politicians, community leaders and experts. We hear far less from “everyday” people and know relatively little about what Jewish and Muslim members of the public are likely to find offensive.

A recent study, published in Ethnic and Racial Studies, is the first known study to compare antisemitism and Islamophobia using statistics and found varying levels of sensitivity towards antisemitism and Islamophobia among British Jewish and Muslim communities. The study offers a rare insight into the sensitivities of “everyday” people within both communities.

More here.

In Conversation: Jonathan Franzen and Andrew Blauner

Poetry and Programming

Brian Kim Stefans at Poetry Magazine:

I often think that my obsession with Ezra Pound’s poetry was due to his well-known formula “DICHTEN = CONDENSARE” (dichten means “to write poetry” but also “to seal” or “to tighten” in German) or to those chestnuts from “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” such as “use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation [of the thing],” all of which was appealing because I was well practiced in reducing these programs to the bare minimum while still achieving their effects. No one wants to play a video game that is too slow or too easy or ends up in an uncontrolled loop (an early version of the spinning pizza of death) because of sloppy coding. One pleasure of programming is reducing many lines of unwieldy code to a few elegant ones, maybe as a function that can be called upon repeatedly. In some ways, I think this is a central pleasure in writing poetry as well—cutting lines, swapping out dull words for lively ones, interjecting a tonal shift that renders some strictly explanatory lines superfluous, and so forth—all while seeing the effect increase as the poem gets smaller.

I often think that my obsession with Ezra Pound’s poetry was due to his well-known formula “DICHTEN = CONDENSARE” (dichten means “to write poetry” but also “to seal” or “to tighten” in German) or to those chestnuts from “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” such as “use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation [of the thing],” all of which was appealing because I was well practiced in reducing these programs to the bare minimum while still achieving their effects. No one wants to play a video game that is too slow or too easy or ends up in an uncontrolled loop (an early version of the spinning pizza of death) because of sloppy coding. One pleasure of programming is reducing many lines of unwieldy code to a few elegant ones, maybe as a function that can be called upon repeatedly. In some ways, I think this is a central pleasure in writing poetry as well—cutting lines, swapping out dull words for lively ones, interjecting a tonal shift that renders some strictly explanatory lines superfluous, and so forth—all while seeing the effect increase as the poem gets smaller.

more here.

Greta Gerwig’s Little Women

Hannah Stamler at Artforum:

Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.”

Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.”

more here.

Word: Jugaad

Mallika Rao at The Believer:

Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles).

Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles).

I first learned the Hindi word in the summer of 2008, which I spent as an intern at a Delhi magazine called Money. A friend in another Indian city—an interloper in the old country, like me—revealed it on a call. She and I loved words. Back in Texas, we had devoured the words of Indian novelists, used them to build an alternate world, a fantasy India, as if our parents had never left (the voluble writers came in handy: Salman Rushdie, with his refracting tales; Vikram Seth, whose A Suitable Boy dropped with a life-changing thud). Jugaad explained a quality we knew about before we had the means to name it. For instance, when our parents took idlis on road trips because they valued fermentation as a preservation method long before Williamsburg shopkeepers taught the world to do the same.

more here.

Who Closes Hospitals?

Andrew Elrod in Dissent:

A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down.

A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down.

Hahnemann is just one of the historic hospitals across the United States that has closed this year while claiming that Medicaid and Medicare payments fail to meet rising costs.

More here.

Galileo’s Error – a new science of consciousness

Galen Strawson in The Guardian:

There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague Charles Darwin, the great evolutionary gradualist, could disagree. Wallace, however, wanted us to have souls; he believed that consciousness was indeed distinct from matter. Darwin was a staunch materialist; he had no doubt that consciousness was wholly material. As early as 1838 he took it for granted that thought is “a secretion of brain”, using the word “thought” in Descartes’s way to cover any conscious experience. He wondered why people found this harder to believe than the fact that gravity is a property of matter. Darwin didn’t explicitly endorse panpsychism – the view that there is an element of consciousness in all matter, or, somewhat more cautiously, that consciousness is one of the fundamental properties of matter. But he saw the force of the position, and saw that it implied our profound ignorance of the nature of matter: “What is matter? the whole thing a mystery”. Certainly he understood the point that William James made in 1890: “If evolution is to work smoothly, consciousness in some shape must have been present at the very origin of things. Accordingly we find that the more clear-sighted evolutionary philosophers are beginning to posit it there.”

There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague Charles Darwin, the great evolutionary gradualist, could disagree. Wallace, however, wanted us to have souls; he believed that consciousness was indeed distinct from matter. Darwin was a staunch materialist; he had no doubt that consciousness was wholly material. As early as 1838 he took it for granted that thought is “a secretion of brain”, using the word “thought” in Descartes’s way to cover any conscious experience. He wondered why people found this harder to believe than the fact that gravity is a property of matter. Darwin didn’t explicitly endorse panpsychism – the view that there is an element of consciousness in all matter, or, somewhat more cautiously, that consciousness is one of the fundamental properties of matter. But he saw the force of the position, and saw that it implied our profound ignorance of the nature of matter: “What is matter? the whole thing a mystery”. Certainly he understood the point that William James made in 1890: “If evolution is to work smoothly, consciousness in some shape must have been present at the very origin of things. Accordingly we find that the more clear-sighted evolutionary philosophers are beginning to posit it there.”

Philip Goff’s engaging Galileo’s Error is a full‑on defence of panpsychism. It’s plainly a difficult view, but when we get serious about consciousness, and put aside the standard bag of philosophical tricks, it seems that one has to choose, with Wallace, between some version of panpsychism or fairytales about immaterial souls. This is of course too simple; Galileo’s Error lays out many of the complexities. It’s an illuminating introduction to the topic of consciousness. It addresses the real issue – unlike almost all recent popular books on this subject. It stands a good chance of delivering the extremely large intellectual jolt that many people will need if they are to get into (or anywhere near) the right ballpark for thinking about consciousness. This is a great thing.

More here.