Cédric Durand in Sidecar:

The stock market valuation of AI-related firms has increased tenfold over the past decade. As John Lanchester noted recently, all but one of the world’s ten largest companies are connected to the future value of artificial intelligence. All but one of those are American, and together their value is equal to well over half of the US economy. Over the past few years, anticipation of the AI ‘revolution’ has driven a surge in investment in these US tech companies. Promises of a radical breakthrough in post-human intelligence and miraculous productivity gains have captured the animal spirits of investors to the point where, as the FT’s Ruchir Sharma put it, ‘America is now one big bet on AI’. Fixed investment in the sector is so enormous that it was the primary driver of US growth in 2025. The training and operation of AI models requires a huge physical build-up of data centres, computing equipment, cooling systems, network hardware, grid connections and power provision. Tech firms are expected to spend a staggering $5 trillion on this costly infrastructure – which is still mostly concentrated in the US – to meet expected demand between now and 2030.

The problem is that the numbers do not add up. To meet its colossal financial needs the sector has shifted from a model dominated by cash-flow and equity financing to debt financing. In principle, this turn to debt could simply reflect growing profit opportunities and the anticipation of forthcoming prosperity. Increasingly exotic financial deals suggest otherwise. A large part of the hype is fuelled by financial loops in which suppliers invest in their clients and vice versa. OpenAI is a case in point. Its leading chip provider, Nvidia – the most valuable company in the world – is planning to invest $100 billion in OpenAI, effectively funding demand for its own products. OpenAI, meanwhile, is spending almost twice what it earns on Microsoft’s cloud platform Azure, which provides the computing power to run its services, thereby enriching its main backer while accumulating debt.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I

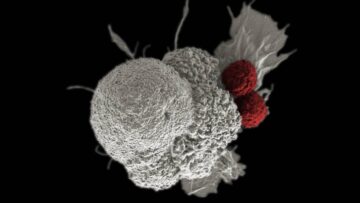

I Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But

Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But  It was just the type of document I was hoping to find.

It was just the type of document I was hoping to find. It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings!

It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings! S.N.S. Sastry’s 1967 documentary film I Am 20 opens with the whistle of a train and the words of T. N. Subramanian, a loquacious young man with a book of chemistry in front. In a nearly 20-minute film documenting the reflections, hopes, and fears of 20-year-old Indians regarding the equally old Indian republic, Subramanian begins with confessing his ambition, much like Mohandas Gandhi who had returned from South Africa, to “go through this country top to bottom” with “a pad and paper, a tape recorder, and a camera… seeing all kinds of people… their anguish and their anger, the fertile soil, the pastures, everything! So that one day when I could come back, I could open the book and remind myself of what I am part of and what is part of me.”

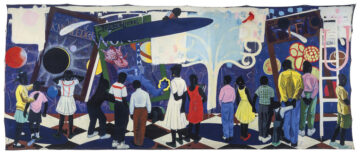

S.N.S. Sastry’s 1967 documentary film I Am 20 opens with the whistle of a train and the words of T. N. Subramanian, a loquacious young man with a book of chemistry in front. In a nearly 20-minute film documenting the reflections, hopes, and fears of 20-year-old Indians regarding the equally old Indian republic, Subramanian begins with confessing his ambition, much like Mohandas Gandhi who had returned from South Africa, to “go through this country top to bottom” with “a pad and paper, a tape recorder, and a camera… seeing all kinds of people… their anguish and their anger, the fertile soil, the pastures, everything! So that one day when I could come back, I could open the book and remind myself of what I am part of and what is part of me.” The artist’s astounding success was by no means predictable when he started out. History painting, the highest of the classical painterly genres as defined by the Royal Academy’s founders, was a distant memory by the 1980s, when the revival of figurative painting and tired Expressionist formulas on both sides of the Atlantic inspired the passionate critiques of Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and his October compatriots. In his well-argued catalogue essay, Godfrey reckons with his own earlier skepticism of figuration, including Marshall’s. As he describes, a visit to the painter’s Chicago studio in 2012 instigated a process of internal interrogation. He came to believe that history painting—if refreshed by new techniques—would speak more directly to audiences, including viewers not typically drawn to museums, than the conceptualist formulas of a prior generation, embracing a position he ascribes to Marshall himself: “As [Marshall] knew, figurative paintings in museums attracted a large audience of experts, first-timers, tourists and schoolchildren, far broader than the niche audience for the lens- and text-based artworks I revered then.” The crowds of teenagers and children listening raptly to the lectures of identical-looking docents in the back-to-back galleries in Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, imagine an art world infinitely more inclusive than the one Marshall entered as a young artist.

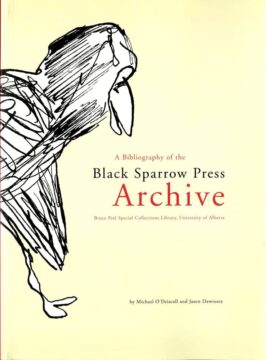

The artist’s astounding success was by no means predictable when he started out. History painting, the highest of the classical painterly genres as defined by the Royal Academy’s founders, was a distant memory by the 1980s, when the revival of figurative painting and tired Expressionist formulas on both sides of the Atlantic inspired the passionate critiques of Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and his October compatriots. In his well-argued catalogue essay, Godfrey reckons with his own earlier skepticism of figuration, including Marshall’s. As he describes, a visit to the painter’s Chicago studio in 2012 instigated a process of internal interrogation. He came to believe that history painting—if refreshed by new techniques—would speak more directly to audiences, including viewers not typically drawn to museums, than the conceptualist formulas of a prior generation, embracing a position he ascribes to Marshall himself: “As [Marshall] knew, figurative paintings in museums attracted a large audience of experts, first-timers, tourists and schoolchildren, far broader than the niche audience for the lens- and text-based artworks I revered then.” The crowds of teenagers and children listening raptly to the lectures of identical-looking docents in the back-to-back galleries in Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, imagine an art world infinitely more inclusive than the one Marshall entered as a young artist. JOHN MARTIN NEVER smoked cigarettes. He did not use drugs or drink alcohol. Martin’s vice was book collecting, which he began in earnest in the late 1930s after he dropped out of UCLA. His enrollment was brief: he left when he discovered that his favorite modern authors, such as Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, and Wallace Stevens, were not on the curriculum.

JOHN MARTIN NEVER smoked cigarettes. He did not use drugs or drink alcohol. Martin’s vice was book collecting, which he began in earnest in the late 1930s after he dropped out of UCLA. His enrollment was brief: he left when he discovered that his favorite modern authors, such as Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, and Wallace Stevens, were not on the curriculum. Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells

Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells  Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …”

Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …” A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird.

A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird.