Christian List in the Boston Review:

Christian List in the Boston Review:

According to the skeptics, human actions aren’t the result of conscious choices but are caused by physical processes in the brain and body over which people have no control. Human beings are just complex physical machines, determined by the laws of nature and prior physical conditions as much as steam engines and the solar system are so determined. The idea of free will, the skeptics say, is a holdover from a naïve worldview that has been refuted by science, just as ghosts and spirits have been refuted. You have as little control over whether to continue to read this article as you have over the date of the next total solar eclipse visible from New York. (It is due to take place on May 1, 2079.)

Such free-will skepticism may not yet be embraced by the general public. Nor is it new; the philosophical debate about whether free will is compatible with determinism stretches back centuries, and the modern scientific debate has been roiling at least since the famous neuroscience experiments on the alleged neural causes of voluntary actions conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s. Still, this skepticism makes trouble for some deeply held views about ourselves. The idea of free will is central to the way we understand ourselves as autonomous agents and to our practices of holding one another responsible.

More here.

Daniel C Dennett and Gregg D Caruso debate free will in Aeon:

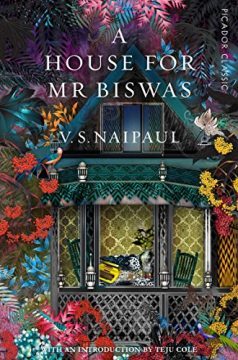

Daniel C Dennett and Gregg D Caruso debate free will in Aeon: V.S. Naipaul in the New York Review of Books:

V.S. Naipaul in the New York Review of Books: Matthew Yglesias in Vox:

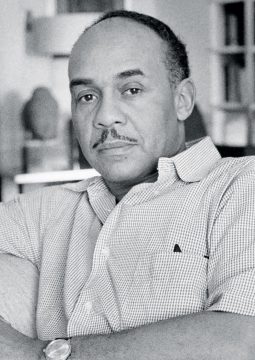

Matthew Yglesias in Vox: ANY OPPORTUNITY TO READ A GREAT WRITER’S MAIL should be embraced in these days when a serial Instagram feed is about as ambitious as correspondence gets. Granted, at roughly a thousand pages, The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison may be asking a lot, at the outset, of even the most committed scholar of twentieth-century American literature, to say nothing of the waves of readers who continue to come away from Invisible Man convinced that it’s the Great American Novel.

ANY OPPORTUNITY TO READ A GREAT WRITER’S MAIL should be embraced in these days when a serial Instagram feed is about as ambitious as correspondence gets. Granted, at roughly a thousand pages, The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison may be asking a lot, at the outset, of even the most committed scholar of twentieth-century American literature, to say nothing of the waves of readers who continue to come away from Invisible Man convinced that it’s the Great American Novel. Before Audrey Hepburn shimmied into that iconic black dress and dangled her cigarette holder between two fingers, the story of Holly Golightly existed only between the covers of Truman Capote’s beloved novella. Way back in 1958, our reviewer summed it up in words that hold true to this day: “‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ is a valentine of love, fashioned by way of reminiscence, to one Holly Golightly … a wild thing searching for something to belong to.”

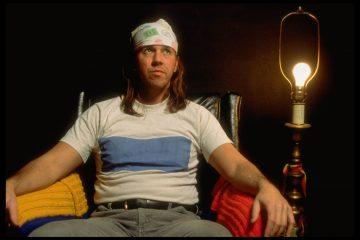

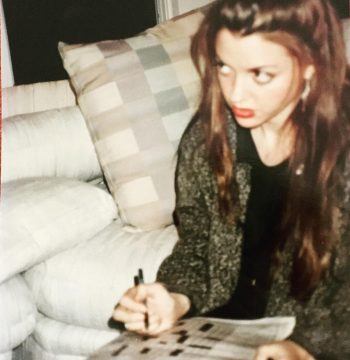

Before Audrey Hepburn shimmied into that iconic black dress and dangled her cigarette holder between two fingers, the story of Holly Golightly existed only between the covers of Truman Capote’s beloved novella. Way back in 1958, our reviewer summed it up in words that hold true to this day: “‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ is a valentine of love, fashioned by way of reminiscence, to one Holly Golightly … a wild thing searching for something to belong to.” A young woman—observant, self-conscious, harboring literary aspirations, though not quite sure where she wants to end up—meets an older novelist, and they start dating. He is as famous as it’s possible for a contemporary writer to be. He is obsessed with his privacy: She is not to draw any attention, occupying a hidden corner of his life. In fact, he sets all the terms of their relationship; the age gap benefits him. While there’s plenty of desire, it’s tinged with condescension (even spite), which contributes more than it should to their sexual tension.

A young woman—observant, self-conscious, harboring literary aspirations, though not quite sure where she wants to end up—meets an older novelist, and they start dating. He is as famous as it’s possible for a contemporary writer to be. He is obsessed with his privacy: She is not to draw any attention, occupying a hidden corner of his life. In fact, he sets all the terms of their relationship; the age gap benefits him. While there’s plenty of desire, it’s tinged with condescension (even spite), which contributes more than it should to their sexual tension.

About 50,000 years ago, ancient humans in what is now West Africa apparently procreated with another group of ancient humans that scientists didn’t know existed.

About 50,000 years ago, ancient humans in what is now West Africa apparently procreated with another group of ancient humans that scientists didn’t know existed. For

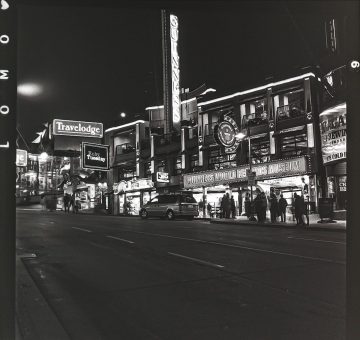

For  Tackiness gets a bad rap because it makes us feel like suckers. It offends our belief that we deserve better. We are allowed to marvel at top-shelf wax statues of celebrities or modern movie blockbusters because they meet some implicit standard of verisimilitude, because they look “real”: it’s okay to be crassly entertained so long as that entertainment passes some bar of acceptability. Anything that fails that standard is generally held to be tawdry or kitschy or cheesy—to be, in other words, beneath our esteem.

Tackiness gets a bad rap because it makes us feel like suckers. It offends our belief that we deserve better. We are allowed to marvel at top-shelf wax statues of celebrities or modern movie blockbusters because they meet some implicit standard of verisimilitude, because they look “real”: it’s okay to be crassly entertained so long as that entertainment passes some bar of acceptability. Anything that fails that standard is generally held to be tawdry or kitschy or cheesy—to be, in other words, beneath our esteem. I had to fight for Prozac Nation because everyone wanted it to be a novel. They really thought that I should write a novelized version of my life. The whole thing was: “Who are you? Why would anybody care about your life? If you’re talented, you can write a novel, because you can invent something.” It’s not like I couldn’t do that. It’s not like it couldn’t have been a novel. But I don’t want to write novels. It’s terrible that men make the rules, and that men have decided that novels are somehow more valuable. It’s really, really, really hard to write about yourself. Women who have written about their own lives should be getting the Nobel Prize. Those are the only people who should be getting the Nobel Prize from now on because it’s really hard to do. It’s not that hard to write about politics. Read a book and you can do it. It’s not that hard to write about Donald Trump, or for that matter Afghanistan. It is really hard to figure out the stuff that scares people. I’m not doing this because I need to figure myself out. I have myself figured out. I’m doing it because other people need to figure themselves out. I’m not writing about myself. I’m writing about other people. It’s a really cheap thing to think that all I’m doing is writing about my life, as if that’s some easy thing.

I had to fight for Prozac Nation because everyone wanted it to be a novel. They really thought that I should write a novelized version of my life. The whole thing was: “Who are you? Why would anybody care about your life? If you’re talented, you can write a novel, because you can invent something.” It’s not like I couldn’t do that. It’s not like it couldn’t have been a novel. But I don’t want to write novels. It’s terrible that men make the rules, and that men have decided that novels are somehow more valuable. It’s really, really, really hard to write about yourself. Women who have written about their own lives should be getting the Nobel Prize. Those are the only people who should be getting the Nobel Prize from now on because it’s really hard to do. It’s not that hard to write about politics. Read a book and you can do it. It’s not that hard to write about Donald Trump, or for that matter Afghanistan. It is really hard to figure out the stuff that scares people. I’m not doing this because I need to figure myself out. I have myself figured out. I’m doing it because other people need to figure themselves out. I’m not writing about myself. I’m writing about other people. It’s a really cheap thing to think that all I’m doing is writing about my life, as if that’s some easy thing. ‘Not all hotels are created equal,’ observes McBride’s narrator; yet ‘once distilled all hotel rooms are essentially alike, if not exactly the same’. She should know: Strange Hotel records an exhausting fictional itinerary of nights spent in, by my count, more than 170 cities, from Dublin to Delhi and further afield. For the most part, these stopovers appear in the simple form of lists, an occasional cryptic ‘x’ denoting, we eventually infer, those occasions when the narrator chooses to forgo her solitude, if not her loneliness, in favour of a casual sexual hook-up. Five rooms, though, come into sharper focus in the novel’s main narrative sections, set in Avignon, Prague, Oslo, Auckland and Austin. Or, more precisely, set in the small and temporarily hospitable space of a hotel room in each city, ‘a place built for people living in a time out of time’.

‘Not all hotels are created equal,’ observes McBride’s narrator; yet ‘once distilled all hotel rooms are essentially alike, if not exactly the same’. She should know: Strange Hotel records an exhausting fictional itinerary of nights spent in, by my count, more than 170 cities, from Dublin to Delhi and further afield. For the most part, these stopovers appear in the simple form of lists, an occasional cryptic ‘x’ denoting, we eventually infer, those occasions when the narrator chooses to forgo her solitude, if not her loneliness, in favour of a casual sexual hook-up. Five rooms, though, come into sharper focus in the novel’s main narrative sections, set in Avignon, Prague, Oslo, Auckland and Austin. Or, more precisely, set in the small and temporarily hospitable space of a hotel room in each city, ‘a place built for people living in a time out of time’. The world’s species and natural ecosystems are in crisis. When nearly 200 countries gather in ten days’ time to thrash out a major plan to stem the precipitous decline, China is expected to take a prominent role. The high-stakes negotiations will set the stage for a major biodiversity summit in October, which the country will also host — marking the first time the nation will lead global talks on the environment. That role as host, together with the China’s growing global influence — including its vast Belt and Road Initiative to build international infrastructure — has thrown a spotlight on its own impact on, and efforts to preserve, biodiversity. “We are familiar with China being part of the problem of the global environmental emergency. For the sake of nature and the people living on this planet, there is a need to turn China into part of the solution,” says Li Shuo, a policy adviser at Greenpeace China in Beijing.

The world’s species and natural ecosystems are in crisis. When nearly 200 countries gather in ten days’ time to thrash out a major plan to stem the precipitous decline, China is expected to take a prominent role. The high-stakes negotiations will set the stage for a major biodiversity summit in October, which the country will also host — marking the first time the nation will lead global talks on the environment. That role as host, together with the China’s growing global influence — including its vast Belt and Road Initiative to build international infrastructure — has thrown a spotlight on its own impact on, and efforts to preserve, biodiversity. “We are familiar with China being part of the problem of the global environmental emergency. For the sake of nature and the people living on this planet, there is a need to turn China into part of the solution,” says Li Shuo, a policy adviser at Greenpeace China in Beijing. A gunshot echoed over starlit forest near the town of Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota. It was late October, already frigid, and chasers had pushed our group of ten fugitives to the edge of a lake. For a moment, we’d hesitated, shouts drawing closer as the black water winked, but the shot drove us all straight in. My legs went numb; Elyse, a high-school sophomore, exclaimed, “My God! ” Submerged to the waist, I waded through marsh grass and lamplight toward our conductor, who silently indicated the opposite bank. The Drinking Gourd shone overhead with exaggerated clarity. This was my third Underground Railroad Reënactment.

A gunshot echoed over starlit forest near the town of Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota. It was late October, already frigid, and chasers had pushed our group of ten fugitives to the edge of a lake. For a moment, we’d hesitated, shouts drawing closer as the black water winked, but the shot drove us all straight in. My legs went numb; Elyse, a high-school sophomore, exclaimed, “My God! ” Submerged to the waist, I waded through marsh grass and lamplight toward our conductor, who silently indicated the opposite bank. The Drinking Gourd shone overhead with exaggerated clarity. This was my third Underground Railroad Reënactment. On the eve of the new year, my Twitter feed and an academic listserv I frequent lit up with arguments about biology and society. Some people had a lot to say about scientific matters—birth sex, assigned sex, genes and chromosomes—while others appealed to social ones: employment rights, free speech, and gender diversity. I could tell that transgender rights lay at the heart of the matter, but why were the people who tagged me on Twitter raging at one another about biological truth? And why were the professionals on my listserv raising disturbing questions about free speech and material reality while also trying to relitigate the meanings of sex and gender?

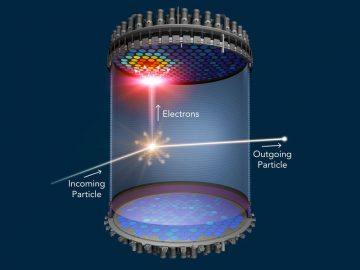

On the eve of the new year, my Twitter feed and an academic listserv I frequent lit up with arguments about biology and society. Some people had a lot to say about scientific matters—birth sex, assigned sex, genes and chromosomes—while others appealed to social ones: employment rights, free speech, and gender diversity. I could tell that transgender rights lay at the heart of the matter, but why were the people who tagged me on Twitter raging at one another about biological truth? And why were the professionals on my listserv raising disturbing questions about free speech and material reality while also trying to relitigate the meanings of sex and gender? This spring, ten tons of liquid xenon will be pumped into a tank nestled nearly a mile underground at the heart of a

This spring, ten tons of liquid xenon will be pumped into a tank nestled nearly a mile underground at the heart of a  This year more than 60 countries will hold

This year more than 60 countries will hold