Michael Walzer in Dissent:

Is liberalism an “ism” like all the other “isms”? I think it once was. In the nineteenth century and for some years in the twentieth, liberalism was an encompassing ideology: free markets, free trade, free speech, open borders, a minimal state, radical individualism, civil liberty, religious toleration, minority rights. But this ideology is now called libertarianism, and most of the people who identify themselves as liberals don’t accept it—at least, not all of it. Liberalism in Europe today is represented by political parties like the German Free Democratic Party that are libertarian and right-wing, but also by parties like the Liberal Democrats in the UK that stand uneasily between conservatives and socialists, taking policies from each side without a strong creed of their own. Liberalism in the United States is our very modest version of social democracy, as in “New Deal liberalism.” This isn’t a strong creed either, as we saw when many liberals of this kind became neoliberals.

“Liberals” are still an identifiable group, and I assume that readers of Dissent are members of the group. We are best described in moral rather than political terms: we are open-minded, generous, tolerant, able to live with ambiguity, ready for arguments that we don’t feel we have to win. Whatever our ideology, whatever our religion, we are not dogmatic; we are not fanatics. Democratic socialists like me can and should be liberals of this kind. I believe that it comes with the territory, though, of course, we all know socialists who are neither open-minded, generous, nor tolerant.

But our actual connection, our political connection, with liberalism has another form. Think of it as an adjectival form: we are, or we should be, liberal democrats and liberal socialists. I am also a liberal nationalist, a liberal communitarian, and a liberal Jew. The adjective works in the same way in all these cases, and my aim here is to describe its force in each of them. Like all adjectives, “liberal” modifies and complicates the noun it precedes; it has an effect that is sometimes constraining, sometimes enlivening, sometimes transforming. It determines not who we are but how we are who we are—how we enact our ideological commitments.

More here.

One of the most vexing questions of the coronavirus pandemic has been how many people have actually been infected. We know that testing has been inadequate, and that many cases of the disease are mild or even asymptomatic, making them less likely to be detected. So how many cases have slipped under the radar? One way to find out the true prevalence of the disease is to test random samples of the population using a blood test that detects antibodies produced by the immune system against the virus. This is different from the swab tests that have been used worldwide throughout the pandemic, which detect the genetic material of the virus itself.

One of the most vexing questions of the coronavirus pandemic has been how many people have actually been infected. We know that testing has been inadequate, and that many cases of the disease are mild or even asymptomatic, making them less likely to be detected. So how many cases have slipped under the radar? One way to find out the true prevalence of the disease is to test random samples of the population using a blood test that detects antibodies produced by the immune system against the virus. This is different from the swab tests that have been used worldwide throughout the pandemic, which detect the genetic material of the virus itself. Why do we categorize novels? Fantasy, Chick Lit, Crime, Romance, Literary, Gothic, Feminist… Is it the better to find what we want, on the carefully labelled shelves of our bookshops? So that the reading experience won’t, after all, be too novel.

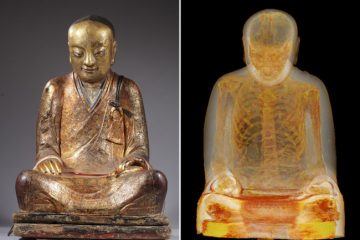

Why do we categorize novels? Fantasy, Chick Lit, Crime, Romance, Literary, Gothic, Feminist… Is it the better to find what we want, on the carefully labelled shelves of our bookshops? So that the reading experience won’t, after all, be too novel. It’s not surprising that Southeast Asia is home to countless ancient Buddha statues, but when one of those statues contains a mummified monk, that is certainly a surprise.

It’s not surprising that Southeast Asia is home to countless ancient Buddha statues, but when one of those statues contains a mummified monk, that is certainly a surprise. It’s jarring how easily the virus has been fused with branding and processed into the optimistic language of advertising. Every crisis begets its own corporate public service announcements — remember the

It’s jarring how easily the virus has been fused with branding and processed into the optimistic language of advertising. Every crisis begets its own corporate public service announcements — remember the  For all his resistance to “anti-art,” Judd articulated most of his motives in the negative. Above all, he was opposed to “illusionism” and “rationalism,” which, in his view, were closely linked. “Three dimensions are real space,” he wrote in “Specific Objects.” “That gets rid of the problem of illusionism.” Why did Judd object to this “relic of European art” so strongly? Again, his argument was not avant-gardist—that abstraction had voided illusionism once and for all (it hadn’t, in any case). Rather, the problem was that illusionism was “anthropomorphic,” by which he meant not simply that it allowed for the representation of the human body, but that it assumed an a priori consciousness, whereby the subject always preceded the object. In short, like composition, illusionism was “rationalistic,” a vestige of an outmoded idealism in need of expunging. “There is little of any of this in the new three-dimensional work,” Judd insisted. “The order is not rationalistic. . . . [It] is simply order, like that of continuity, one thing after another.”

For all his resistance to “anti-art,” Judd articulated most of his motives in the negative. Above all, he was opposed to “illusionism” and “rationalism,” which, in his view, were closely linked. “Three dimensions are real space,” he wrote in “Specific Objects.” “That gets rid of the problem of illusionism.” Why did Judd object to this “relic of European art” so strongly? Again, his argument was not avant-gardist—that abstraction had voided illusionism once and for all (it hadn’t, in any case). Rather, the problem was that illusionism was “anthropomorphic,” by which he meant not simply that it allowed for the representation of the human body, but that it assumed an a priori consciousness, whereby the subject always preceded the object. In short, like composition, illusionism was “rationalistic,” a vestige of an outmoded idealism in need of expunging. “There is little of any of this in the new three-dimensional work,” Judd insisted. “The order is not rationalistic. . . . [It] is simply order, like that of continuity, one thing after another.” So what happens when someone sets out to write fiction that is “100 percent pornographic and 100 percent high art”? According to Garth Greenwell, that was one of his goals in writing Cleanness, a collection of stories so connected they can be read as a novel (he himself has called the book a lieder cycle) and which includes several graphic descriptions of sex, some loving and tender, some brutally S&M, and all tending to read autobiographically. (Like his fictional unnamed first-person narrator, Greenwell is gay, was raised in a southern Republican state, and has lived and taught in Bulgaria. A recent profile in The New York Times suggested that, despite these parallels, readers who assume Greenwell is writing about himself are mistaken. However, when I asked him if it would be appropriate for me to include his work in a course I taught on autobiographical fiction, and if I had his approval to do so, he said yes.)

So what happens when someone sets out to write fiction that is “100 percent pornographic and 100 percent high art”? According to Garth Greenwell, that was one of his goals in writing Cleanness, a collection of stories so connected they can be read as a novel (he himself has called the book a lieder cycle) and which includes several graphic descriptions of sex, some loving and tender, some brutally S&M, and all tending to read autobiographically. (Like his fictional unnamed first-person narrator, Greenwell is gay, was raised in a southern Republican state, and has lived and taught in Bulgaria. A recent profile in The New York Times suggested that, despite these parallels, readers who assume Greenwell is writing about himself are mistaken. However, when I asked him if it would be appropriate for me to include his work in a course I taught on autobiographical fiction, and if I had his approval to do so, he said yes.) In 1906 in England, literature was dominated by the well-behaved worlds of novelists such as Arnold Bennett, EM Forster and John Galsworthy. At the same time in Italy, Marta Felicina Faccio, who later became a leading feminist, published her first book under the pseudonym Sibilla Aleramo. A Woman is a groundbreaking, earthquaking vision, a story and a manifesto, and a literary performance so energetic it almost demands to be read aloud.

In 1906 in England, literature was dominated by the well-behaved worlds of novelists such as Arnold Bennett, EM Forster and John Galsworthy. At the same time in Italy, Marta Felicina Faccio, who later became a leading feminist, published her first book under the pseudonym Sibilla Aleramo. A Woman is a groundbreaking, earthquaking vision, a story and a manifesto, and a literary performance so energetic it almost demands to be read aloud. I

I

When the history is written of how America handled the global era’s first real pandemic, March 6 will leap out of the timeline. That was the day Donald Trump visited the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. His foray to the world’s best disease research body was meant to showcase that America had everything under control. It came midway between the time he was still denying the coronavirus posed a threat and the moment he said he had always known it could ravage America.

When the history is written of how America handled the global era’s first real pandemic, March 6 will leap out of the timeline. That was the day Donald Trump visited the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. His foray to the world’s best disease research body was meant to showcase that America had everything under control. It came midway between the time he was still denying the coronavirus posed a threat and the moment he said he had always known it could ravage America.

The Diamond Princess has a steakhouse, a pizzeria and restaurants specialising in sushi and Italian cuisine. Buffets offer prime rib, escargots and crème brûlée, all served in gigantic portions at every hour of the day or night. The ship has its own mixologist, sommelier and chocolatier.

The Diamond Princess has a steakhouse, a pizzeria and restaurants specialising in sushi and Italian cuisine. Buffets offer prime rib, escargots and crème brûlée, all served in gigantic portions at every hour of the day or night. The ship has its own mixologist, sommelier and chocolatier. History, literature, film, and scripture are loaded with stories and examples of redemption. Buddhism gives us the story of Aṅgulimāla, a pathological mass-murderer who became a follower of the Buddha and went on to be enshrined as a “patron saint” of childbirth in South and Southeast Asia. Rick Blaine, the character played by Humphrey Bogart in the 1942 Hollywood classic Casablanca, put side his cynical bitterness and seeming indifference to the rise of the Nazi Third Reich to help Isla Lund (played by Ingmar Bergman) – the former lover who jilted (and embittered) him – escape the grip of the Nazis with her husband, an anti-fascist Resistance fighter. The movie ends with Blaine declaring his determination to join the Resistance in Morocco. The New Testament tells the story of Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector and a wealthy man:

History, literature, film, and scripture are loaded with stories and examples of redemption. Buddhism gives us the story of Aṅgulimāla, a pathological mass-murderer who became a follower of the Buddha and went on to be enshrined as a “patron saint” of childbirth in South and Southeast Asia. Rick Blaine, the character played by Humphrey Bogart in the 1942 Hollywood classic Casablanca, put side his cynical bitterness and seeming indifference to the rise of the Nazi Third Reich to help Isla Lund (played by Ingmar Bergman) – the former lover who jilted (and embittered) him – escape the grip of the Nazis with her husband, an anti-fascist Resistance fighter. The movie ends with Blaine declaring his determination to join the Resistance in Morocco. The New Testament tells the story of Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector and a wealthy man: