Apurv Mishra in Scientific American:

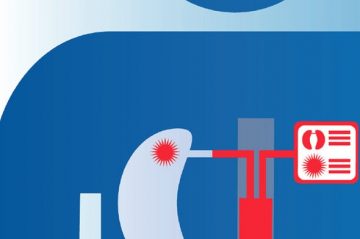

A patient suspected of having cancer usually undergoes imaging and a biopsy. Samples of the tumor are excised, examined under a microscope and, often, analyzed to pinpoint the genetic mutations responsible for the malignancy. Together, this information helps to determine the type of cancer, how advanced it is and how best to treat it. Yet sometimes biopsies cannot be done, such as when a tumor is hard to reach. Obtaining and analyzing the tissue can also be expensive and slow. And because biopsies are invasive, they may cause infections or other complications.

A patient suspected of having cancer usually undergoes imaging and a biopsy. Samples of the tumor are excised, examined under a microscope and, often, analyzed to pinpoint the genetic mutations responsible for the malignancy. Together, this information helps to determine the type of cancer, how advanced it is and how best to treat it. Yet sometimes biopsies cannot be done, such as when a tumor is hard to reach. Obtaining and analyzing the tissue can also be expensive and slow. And because biopsies are invasive, they may cause infections or other complications.

A tool known as a liquid biopsy—which finds signs of cancer in a simple blood sample—promises to solve those problems and more. A few dozen companies are developing their own technologies, and observers predict that the market for the tests could be worth billions. The technique typically homes in on circulating-tumor DNA (ctDNA), genetic material that routinely finds its way from cancer cells into the bloodstream. Only recently have advanced technologies made it possible to find, amplify and sequence the DNA rapidly and inexpensively.

More here.

I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits.

I was slightly nervous before my first meeting with the author Mirza Athar Baig, in the winter of 2017, at the Big M restaurant in Lahore’s Shadman Market. I had recently signed a book deal for my translation of his 2014 Urdu novel Hassan’s State of Affairs, and I was meeting him to discuss the first round of edits. Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

Cooking is art, but it’s also very much science — mostly chemistry, but with important contributions from physics and biology. (Almost like a well-balanced recipe…) And I can’t think of anyone better to talk to about the intersection of these fields than Kenji López-Alt: professional chef and restauranteur, MIT graduate, and author of The Food Lab. We discuss how modern scientific ideas can improve your cooking, and more importantly, how to bring a scientific approach to cooking anything at all. Then we also get into the cultural and personal resonance of food, and offer a few practical tips.

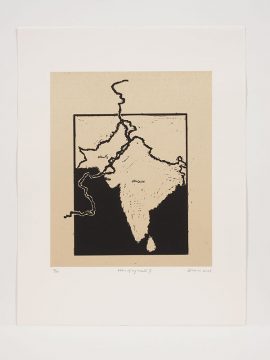

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the

In a short video documentary produced by the Tate Modern in London, the artist talks about her exhibition, “Letters from Home,” which opened on 28 March 2013. Through personal letters, the exhibition illustrates an immigrant’s disconnection from his or her homeland. In the  The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”

The real saga of the Statue of Liberty—the symbolic face of America around the world, and the backdrop of New York’s dazzling Fourth of July fireworks show—is an obscure piece of U.S. history. It had nothing to do with immigration. The telltale clue is the chain under Lady Liberty’s feet: she is stomping on it. “In the early sketches, she was also holding chains in her hand,”  The first thing that strikes the reader about Yahia Lababidi’s

The first thing that strikes the reader about Yahia Lababidi’s  Robert Brenner in New Left Review:

Robert Brenner in New Left Review: An interview with Wendy Brown in The Drift:

An interview with Wendy Brown in The Drift:

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discoveries of recent years have been in genetic history. It has already been several decades since the study of DNA revealed how little substance there was to claims of racial difference. Study of genetic material found in ancient bones also suggests that, rather than a single migration out of Africa, humans populated the globe in waves that intermingled, coming back as well as going forwards. “We weren’t migrants once in the distant past and then again in the most recent era,” Shah writes. “We’ve been migrants all along.”

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discoveries of recent years have been in genetic history. It has already been several decades since the study of DNA revealed how little substance there was to claims of racial difference. Study of genetic material found in ancient bones also suggests that, rather than a single migration out of Africa, humans populated the globe in waves that intermingled, coming back as well as going forwards. “We weren’t migrants once in the distant past and then again in the most recent era,” Shah writes. “We’ve been migrants all along.” Angela said she had read Cusk’s newest book on the plane over. It slowly dawned on her that the essays in that collection contemplate a variety of ostracisms: from being given the silent treatment by one’s own parents to the exclusion of women writers from the literary canon. Aftermath, Medea, the Outline trilogy – they’re all about being cast out into the wilderness. In an essay called ‘Coventry’ Cusk characterises such exile as ‘ejection from the story’. The only thing to do once you’re ‘living amidst the waste and shattered buildings, the desecrated past’ is to search ‘for whatever truth might be found amid the smoking ruins’.

Angela said she had read Cusk’s newest book on the plane over. It slowly dawned on her that the essays in that collection contemplate a variety of ostracisms: from being given the silent treatment by one’s own parents to the exclusion of women writers from the literary canon. Aftermath, Medea, the Outline trilogy – they’re all about being cast out into the wilderness. In an essay called ‘Coventry’ Cusk characterises such exile as ‘ejection from the story’. The only thing to do once you’re ‘living amidst the waste and shattered buildings, the desecrated past’ is to search ‘for whatever truth might be found amid the smoking ruins’.