Francis Collins in NIH Director’s Blog:

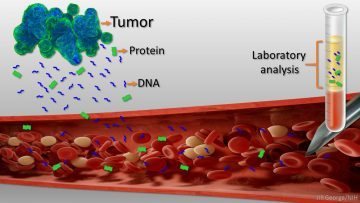

Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Recently, an NIH-funded research team reported some encouraging results using a “universal” liquid biopsy called CancerSEEK [1]. By analyzing samples of a person’s blood for eight proteins and segments of 16 genes, CancerSEEK was able to detect most cases of eight different kinds of cancer, including some highly lethal forms—such as pancreatic, ovarian, and liver—that currently lack screening tests. In a study of 1,005 people known to have one of eight early-stage tumor types, CancerSEEK detected the cancer in blood about 70 percent of the time, which is among the best performances to date for a blood test. Importantly, when CancerSEEK was performed on 812 healthy people without cancer, the test rarely delivered a false-positive result. The test can also be run relatively cheaply, at an estimated cost of less than $500.

Cancers arise when gene mutations occur in individual cells, dysregulating their normal growth and allowing them to divide without the usual restraints. As the clump of cancer cells expands, some die and bits of their mutated DNA can end up in the bloodstream. Liquid biopsies then search the blood for those bits of DNA carrying mutations associated with cancer. In 2016, the FDA approved the first liquid biopsy test for detecting a single mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer for use in guiding treatment decisions of people already known to have this type of cancer [2]. But developing a liquid biopsy test that could screen apparently healthy people for a variety of early cancers has proven a much greater challenge.

More here.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized. Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?

Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?

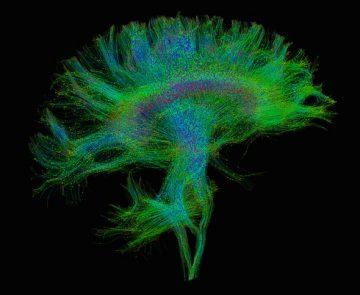

What makes the human brain special? That question is not easy to answer—and will occupy neuroscientists for generations to come. But a few tentative responses can already be mustered. The organ is certainly bigger than expected for our body size. And it has its own specialized areas—one of which is devoted to processing language. In recent years, brain scans have started to show that the particular way neurons connect to one another is also part of the story. A key tool in these studies is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—in particular, a version known as diffusion tensor imaging. This technique can visualize the long fibers that extend out from neurons and link brain regions without having to remove a piece of skull. Like wires, these connections carry electrical information between neurons. And the aggregate of all these links, also known as a connectome, can provide clues about how the brain processes information.

What makes the human brain special? That question is not easy to answer—and will occupy neuroscientists for generations to come. But a few tentative responses can already be mustered. The organ is certainly bigger than expected for our body size. And it has its own specialized areas—one of which is devoted to processing language. In recent years, brain scans have started to show that the particular way neurons connect to one another is also part of the story. A key tool in these studies is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—in particular, a version known as diffusion tensor imaging. This technique can visualize the long fibers that extend out from neurons and link brain regions without having to remove a piece of skull. Like wires, these connections carry electrical information between neurons. And the aggregate of all these links, also known as a connectome, can provide clues about how the brain processes information. W

W W

W Sanjay G. Reddy over at Reddy to Read:

Sanjay G. Reddy over at Reddy to Read: Ragnar Fjelland in Nature:

Ragnar Fjelland in Nature: Göran Therborn in The Conversation:

Göran Therborn in The Conversation: Sophie Gilbert in The Atlantic:

Sophie Gilbert in The Atlantic: The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, paved the way for American women to vote, but the educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune knew the work had only just begun: The amendment alone would not guarantee political power to black women. Thanks to Bethune’s work that year to register and mobilize black voters in her hometown of Daytona, Florida, new black voters soon outnumbered new white voters in the city. But a reign of terror followed. That fall, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Bethune’s boarding school for black girls; two years later, ahead of the 1922 elections, the Klan paid another threatening visit, as over 100 robed figures carrying banners emblazoned with the words “white supremacy” marched on the school in retaliation against Bethune’s continued efforts to get black women to the polls. Informed of the incoming nightriders, Bethune took charge: “Get the students into the dormitory,” she told the teachers, “get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” The students safely tucked in, Bethune directed her faculty: “The Ku Klux Klan is marching on our campus, and they intend to burn some buildings.”

The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, paved the way for American women to vote, but the educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune knew the work had only just begun: The amendment alone would not guarantee political power to black women. Thanks to Bethune’s work that year to register and mobilize black voters in her hometown of Daytona, Florida, new black voters soon outnumbered new white voters in the city. But a reign of terror followed. That fall, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Bethune’s boarding school for black girls; two years later, ahead of the 1922 elections, the Klan paid another threatening visit, as over 100 robed figures carrying banners emblazoned with the words “white supremacy” marched on the school in retaliation against Bethune’s continued efforts to get black women to the polls. Informed of the incoming nightriders, Bethune took charge: “Get the students into the dormitory,” she told the teachers, “get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” The students safely tucked in, Bethune directed her faculty: “The Ku Klux Klan is marching on our campus, and they intend to burn some buildings.” More research emerged this week in potential support of using the tuberculosis vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (

More research emerged this week in potential support of using the tuberculosis vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (