Sam Moyn over at the Quincy Institute:

Sam Moyn over at the Quincy Institute:

Since September 11, 2001, American policy in matters of war has abandoned the restraints in the U.S. Constitution and international law, with grievous results not merely for wrongful victims of war (such as the abused captives in Guantánamo Bay or civilians killed in drone strikes) but also for those whom the laws governing how war is conducted were never devised to protect. In focusing exclusively on harms to abused captives and civilians killed as “collateral damage,” American debate has ignored a wider set of wrongs. These include the death and injury of fighters themselves on both sides, including long-term post-traumatic stress; the fate of populations under increasing surveillance and constant threat of force; and the enormous costs of an “endless war” footing that whole societies must bear. In the American case, these costs come to trillions of dollars.

With rare exceptions, debate has focused in the honorable but wrong place: on making the conduct of war less brutal and more plausibly legal.[1] In the later years of George W. Bush’s administration, the United States sought to make his war on terror more humane while lending it greater legitimacy; the harshest treatments of detainees, notably those fairly considered torture, were eliminated. The ironic result was that the war on terror endured. Endless war was elaborated during the presidency of Barack Obama, with its pivot away from heavy-footprint interventions to light– and no-footprint operations involving armed drones, standoff missiles, and special forces. Surprisingly, the same pattern has continued under President Donald Trump. His rhetoric of brutality and his contradictory promises to bring troops home notwithstanding, Trump has adopted no dramatically new methods while intensifying many of the conflicts he inherited.

More here.

Sarah Stoller in Aeon:

Sarah Stoller in Aeon: Hassina Mechaï over at the Verso blog:

Hassina Mechaï over at the Verso blog: When I think that it won’t hurt too much, I imagine the children I will not have. Would they be more like me or my partner? Would they have inherited my thatch of hair, our terrible eyesight? Mostly, a child is so abstract to me, living with high rent, student debt, no property and no room, that the absence barely registers. But sometimes I suddenly want a daughter with the same staggering intensity my father felt when he first cradled my tiny body in his big hands. I want to feel that reassuring weight, a reminder of the persistence of life.

When I think that it won’t hurt too much, I imagine the children I will not have. Would they be more like me or my partner? Would they have inherited my thatch of hair, our terrible eyesight? Mostly, a child is so abstract to me, living with high rent, student debt, no property and no room, that the absence barely registers. But sometimes I suddenly want a daughter with the same staggering intensity my father felt when he first cradled my tiny body in his big hands. I want to feel that reassuring weight, a reminder of the persistence of life. In early April, at the height of the pandemic lockdown, Gianpiero Petriglieri, an Italian business professor, suggested on Twitter that being forced to conduct much of our lives online was making us sick. The constant video calls and Zoom meetings were draining us because they go against our brain’s need for boundaries: here versus not here. “It’s easier being in each other’s presence, or in each other’s absence,” he wrote, “than in the constant presence of each other’s absence.”

In early April, at the height of the pandemic lockdown, Gianpiero Petriglieri, an Italian business professor, suggested on Twitter that being forced to conduct much of our lives online was making us sick. The constant video calls and Zoom meetings were draining us because they go against our brain’s need for boundaries: here versus not here. “It’s easier being in each other’s presence, or in each other’s absence,” he wrote, “than in the constant presence of each other’s absence.” I must admit

I must admit GIVEN THAT SHE

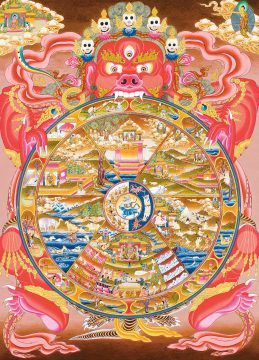

GIVEN THAT SHE In any case, for me—like many Buddhists, past and present—the most frightening part of karma isn’t a vision of torments in the next life, but the idea that my suffering in this life isn’t altogether random or circumstantial; it carries the trace of some previous action along with it. There’s something unbearable about causality when we think about it in the strictest terms: A virus, for example, can be transmitted through the simplest unconscious act, like scratching your nose with the same finger that was just wrapped around a subway pole. In contemporary physics, the limits of causality are explored in the field known as “quantum entanglement,” or what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance”: that is, the ability of distant entities to influence one another with no apparent force (like gravity) connecting them. Physicists know quantum entanglement happens, but how it works, and what power it exerts over everyday objects, is a subject of much debate.

In any case, for me—like many Buddhists, past and present—the most frightening part of karma isn’t a vision of torments in the next life, but the idea that my suffering in this life isn’t altogether random or circumstantial; it carries the trace of some previous action along with it. There’s something unbearable about causality when we think about it in the strictest terms: A virus, for example, can be transmitted through the simplest unconscious act, like scratching your nose with the same finger that was just wrapped around a subway pole. In contemporary physics, the limits of causality are explored in the field known as “quantum entanglement,” or what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance”: that is, the ability of distant entities to influence one another with no apparent force (like gravity) connecting them. Physicists know quantum entanglement happens, but how it works, and what power it exerts over everyday objects, is a subject of much debate. Of course, I had seen, next to the Gentleman’s Relish, the box of finely dusted Turkish delight, the halva, the packets of rosti; I had been with him to his birthplace in Romania and seen the places of his childhood, not once but twice; together with Alexander, I had been in the ancient forests with him, had picked wild raspberries and cracked open hazelnuts with a stone. I had helped him fill the box of Christmas gifts for our cousins stuck behind the Iron Curtain: chocolate, vitamins, medicine, Marmite, jam, tinned sardines, winter gloves and hats, stockings. But these things had featured only in the margin of my map of my father. At least, until that day when my friend asked: ‘Where’s your father from?’ More than thirty years have passed, and still I hover in the same state of postponed understanding, like the delayed response after the turning of a ship’s wheel or the pulling of a bell rope. Where was he from? Why do I need to know? Will I feel better if I do?

Of course, I had seen, next to the Gentleman’s Relish, the box of finely dusted Turkish delight, the halva, the packets of rosti; I had been with him to his birthplace in Romania and seen the places of his childhood, not once but twice; together with Alexander, I had been in the ancient forests with him, had picked wild raspberries and cracked open hazelnuts with a stone. I had helped him fill the box of Christmas gifts for our cousins stuck behind the Iron Curtain: chocolate, vitamins, medicine, Marmite, jam, tinned sardines, winter gloves and hats, stockings. But these things had featured only in the margin of my map of my father. At least, until that day when my friend asked: ‘Where’s your father from?’ More than thirty years have passed, and still I hover in the same state of postponed understanding, like the delayed response after the turning of a ship’s wheel or the pulling of a bell rope. Where was he from? Why do I need to know? Will I feel better if I do? In 2019, 62 worshippers performing Friday prayers were killed by a bomb blast in Nangarhar. Back in 2002, a fire broke out at a girl’s school in Makkah. Fifteen young girls died and 50 injured, allegedly because they were beaten back to go inside: they had not covered their heads. In 1987, more than 400 unarmed pilgrims, mostly Iranians, were killed in Makkah during a protest. The list goes on. One fact stands out: most of the outpouring of anger, sympathy and concern came from non-Muslim organisations, people and countries. Muslims were, by and large, silent. Even as the world seems to have come closer, with a more formalised structure of human rights, it has regressed into increasing hatred and acts of violence against the ‘other’, whoever it might be. It took the Christians six centuries of religiously supported wars and torture against Muslims and Jews to decide that they could safely replace religion with science. They colonised, ridiculed Muslims, spread false rumours, destroyed traditions of Muslim scholarship and weakened Muslim societies through carefully orchestrated propaganda. Islamophobia has increased since 9/11 with Muslims being held in Guantanamo Bay prison and tortured. Very few Muslim governments stood up to help them.

In 2019, 62 worshippers performing Friday prayers were killed by a bomb blast in Nangarhar. Back in 2002, a fire broke out at a girl’s school in Makkah. Fifteen young girls died and 50 injured, allegedly because they were beaten back to go inside: they had not covered their heads. In 1987, more than 400 unarmed pilgrims, mostly Iranians, were killed in Makkah during a protest. The list goes on. One fact stands out: most of the outpouring of anger, sympathy and concern came from non-Muslim organisations, people and countries. Muslims were, by and large, silent. Even as the world seems to have come closer, with a more formalised structure of human rights, it has regressed into increasing hatred and acts of violence against the ‘other’, whoever it might be. It took the Christians six centuries of religiously supported wars and torture against Muslims and Jews to decide that they could safely replace religion with science. They colonised, ridiculed Muslims, spread false rumours, destroyed traditions of Muslim scholarship and weakened Muslim societies through carefully orchestrated propaganda. Islamophobia has increased since 9/11 with Muslims being held in Guantanamo Bay prison and tortured. Very few Muslim governments stood up to help them. The story began earlier this week, when Yoho reportedly approached Ocasio-Cortez on the Capitol steps to inform her that she was, among other things, “disgusting” and “out of your freaking mind.” His analysis was directed at her (hardly novel) public statements that poverty and unemployment are root causes of the recent spike in crime rates in New York. On matters of criminal-justice reform, Yoho is of a decidedly conservative bent. Not long ago, he voted against making lynching a federal hate crime, saying that such a law would be a regrettable instance of federal “overreach.” According to a reporter for

The story began earlier this week, when Yoho reportedly approached Ocasio-Cortez on the Capitol steps to inform her that she was, among other things, “disgusting” and “out of your freaking mind.” His analysis was directed at her (hardly novel) public statements that poverty and unemployment are root causes of the recent spike in crime rates in New York. On matters of criminal-justice reform, Yoho is of a decidedly conservative bent. Not long ago, he voted against making lynching a federal hate crime, saying that such a law would be a regrettable instance of federal “overreach.” According to a reporter for  Melanie Rutkowski, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology, found that

Melanie Rutkowski, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology, found that  Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg grew up with a solid old-school Brooklyn accent. She displays no trace of it in recordings of her work as a young litigator, but today, one can hear shades of it in her speech on and off the court. Why?

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg grew up with a solid old-school Brooklyn accent. She displays no trace of it in recordings of her work as a young litigator, but today, one can hear shades of it in her speech on and off the court. Why? There’s a

There’s a  When moral visions clash, it’s common for people to assume their opponents have bad motives rather than different perspectives. And it’s usually wrong. If you advocate some policy you believe will save lives, whether it’s a plan for fighting COVID-19, increasing health-care coverage, or reducing homicide, your opponents probably don’t oppose your plan because they want more people to die. They may think their own plan will save lives, or they may be concerned about other values entirely. You may very well have fundamental moral disagreements with them, but the thing you hate most about their position probably isn’t what’s driving them.

When moral visions clash, it’s common for people to assume their opponents have bad motives rather than different perspectives. And it’s usually wrong. If you advocate some policy you believe will save lives, whether it’s a plan for fighting COVID-19, increasing health-care coverage, or reducing homicide, your opponents probably don’t oppose your plan because they want more people to die. They may think their own plan will save lives, or they may be concerned about other values entirely. You may very well have fundamental moral disagreements with them, but the thing you hate most about their position probably isn’t what’s driving them.