Jesse McCarthy in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

The memoirs of Black revolutionaries have been, almost by definition, exceptional in their narratives, exemplary in their aspirations, and dispirited in their conclusions. Traditionally, the disappointment of unfinished and unrealized ambitions is mitigated by a rhetorical appeal to continued struggle and hope for a future Black liberation that the memoirists themselves will not live to see. They look to the future to say: One day. In time we will find our way to freedom, equality, self-loving, and self-respecting — to fully enjoying whatever the best of the human condition ought to entail. But what if the condition of being human is so thoroughly racialized that even appealing to it only further distances them from the possibility of its realization? What if, moreover, the destruction of Black people is not a contingent difficulty that can be corrected, but a necessary fate because the very category of “the human” is premised on their negation? As Frank Wilderson puts it, what if “Human life is dependent on Black death for its existence and for its conceptual coherence”?

The memoirs of Black revolutionaries have been, almost by definition, exceptional in their narratives, exemplary in their aspirations, and dispirited in their conclusions. Traditionally, the disappointment of unfinished and unrealized ambitions is mitigated by a rhetorical appeal to continued struggle and hope for a future Black liberation that the memoirists themselves will not live to see. They look to the future to say: One day. In time we will find our way to freedom, equality, self-loving, and self-respecting — to fully enjoying whatever the best of the human condition ought to entail. But what if the condition of being human is so thoroughly racialized that even appealing to it only further distances them from the possibility of its realization? What if, moreover, the destruction of Black people is not a contingent difficulty that can be corrected, but a necessary fate because the very category of “the human” is premised on their negation? As Frank Wilderson puts it, what if “Human life is dependent on Black death for its existence and for its conceptual coherence”?

Understanding how Wilderson has come to such a conclusion requires a glance at his own exceptionally restless and revolutionary life.

More here.

We are living, in case you haven’t noticed, in a world full of bullshit. It’s hard to say whether the amount is truly increasing, but it seems that everywhere you look someone is trying to convince you of something, regardless of whether that something is actually true. Where is this bullshit coming from, how is it disseminated, and what can we do about it? Carl Bergstrom studies information in the context of biology, which has led him to investigate the flow of information and disinformation in social networks, especially the use of data in misleading ways. In the time of Covid-19 he has become on of the best Twitter feeds for reliable information, and we discuss how the pandemic has been a bounteous new source of bullshit.

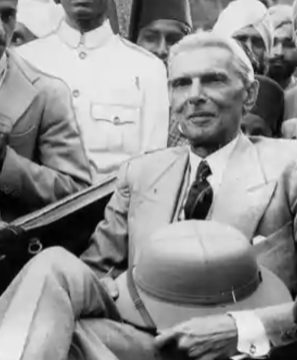

We are living, in case you haven’t noticed, in a world full of bullshit. It’s hard to say whether the amount is truly increasing, but it seems that everywhere you look someone is trying to convince you of something, regardless of whether that something is actually true. Where is this bullshit coming from, how is it disseminated, and what can we do about it? Carl Bergstrom studies information in the context of biology, which has led him to investigate the flow of information and disinformation in social networks, especially the use of data in misleading ways. In the time of Covid-19 he has become on of the best Twitter feeds for reliable information, and we discuss how the pandemic has been a bounteous new source of bullshit. The peculiarity of hindsight is that it depends on the point from which you look back at Pakistan’s and India’s trajectories. In the early 1970s and till the late 1990s, as Pakistan itself broke up into two and generals and mullahs controlled its politics, India could afford to be smug. In 1992, the destruction of the Babri Masjid changed that, and the consequences of India’s 2014 election are there for us to see. Some Pakistanis may feel triumphant, but the virtue of Pakistani lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani’s new biography, Jinnah: A Life, is that it takes a sober tone.

The peculiarity of hindsight is that it depends on the point from which you look back at Pakistan’s and India’s trajectories. In the early 1970s and till the late 1990s, as Pakistan itself broke up into two and generals and mullahs controlled its politics, India could afford to be smug. In 1992, the destruction of the Babri Masjid changed that, and the consequences of India’s 2014 election are there for us to see. Some Pakistanis may feel triumphant, but the virtue of Pakistani lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani’s new biography, Jinnah: A Life, is that it takes a sober tone. Bishop published only about a hundred poems during her lifetime, but won the most prestigious prizes for American literature: the Pulitzer in 1956 and the National Book Award in 1970. Brilliant, quirky critic Randall Jarrell described her poems as “honest, modest, minutely observant, masterly. . . . The poems are like Vuillard or even, sometimes, Vermeer.” Bishop was overwhelmed: “It has always been one of my dreams that someday someone would think of Vermeer, without my saying it first”—adding cheerfully, “So now I think I can die in a fairly peaceful frame of mind any old time.” Her life was tumultuous and tragic, but also filled with love and lust. Bishop’s father died when she was only a few months old, a loss her mother, mentally unstable Gertrude Bulmer, never overcame. Her loving, but simple, maternal grandparents raised Bishop in Great Village, a hamlet in Nova Scotia, Canada, during her infancy, while Bulmer was locked up in an insane asylum for long periods. When Bishop was five years old, Bulmer was put away forever, mostly in solitary confinement. She would never see her mother again. Soon after, suddenly, her father’s parents took her to Worcester, Massachusetts, and Bishop ended up in a world that was less austere, but much colder and more distant. Lonely and alone, she was plagued by terrible asthma and eczema; Travisano convincingly argues that these had psychosomatic origins.

Bishop published only about a hundred poems during her lifetime, but won the most prestigious prizes for American literature: the Pulitzer in 1956 and the National Book Award in 1970. Brilliant, quirky critic Randall Jarrell described her poems as “honest, modest, minutely observant, masterly. . . . The poems are like Vuillard or even, sometimes, Vermeer.” Bishop was overwhelmed: “It has always been one of my dreams that someday someone would think of Vermeer, without my saying it first”—adding cheerfully, “So now I think I can die in a fairly peaceful frame of mind any old time.” Her life was tumultuous and tragic, but also filled with love and lust. Bishop’s father died when she was only a few months old, a loss her mother, mentally unstable Gertrude Bulmer, never overcame. Her loving, but simple, maternal grandparents raised Bishop in Great Village, a hamlet in Nova Scotia, Canada, during her infancy, while Bulmer was locked up in an insane asylum for long periods. When Bishop was five years old, Bulmer was put away forever, mostly in solitary confinement. She would never see her mother again. Soon after, suddenly, her father’s parents took her to Worcester, Massachusetts, and Bishop ended up in a world that was less austere, but much colder and more distant. Lonely and alone, she was plagued by terrible asthma and eczema; Travisano convincingly argues that these had psychosomatic origins. In making these claims about academic writing, I am thinking in the first instance of my own corner of academia—philosophy—though I suspect that my points generalize, at least over the academic humanities. To offer up one anecdote: in spring 2019 I was teaching Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; since I don’t usually teach literature, I thought I should check out recent secondary literature on Joyce. What I found was abstruse and hypercomplex, laden with terminology and indirect. I didn’t feel I was learning anything I could use to make the meaning of the novel more accessible to myself or to my students. I am willing to take some of the blame here: I am sure I could have gotten something out of those pieces if I had been willing to put more effort into reading them. Still, I do not lack the intellectual competence required to understand analyses of Joyce; I feel all of those writers could have done more to write for me.

In making these claims about academic writing, I am thinking in the first instance of my own corner of academia—philosophy—though I suspect that my points generalize, at least over the academic humanities. To offer up one anecdote: in spring 2019 I was teaching Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; since I don’t usually teach literature, I thought I should check out recent secondary literature on Joyce. What I found was abstruse and hypercomplex, laden with terminology and indirect. I didn’t feel I was learning anything I could use to make the meaning of the novel more accessible to myself or to my students. I am willing to take some of the blame here: I am sure I could have gotten something out of those pieces if I had been willing to put more effort into reading them. Still, I do not lack the intellectual competence required to understand analyses of Joyce; I feel all of those writers could have done more to write for me.

Back in the ’30s — the 1130s — the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth created the impression that Stonehenge was built as a memorial to a bunch of British nobles slain by the Saxons. In his “

Back in the ’30s — the 1130s — the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth created the impression that Stonehenge was built as a memorial to a bunch of British nobles slain by the Saxons. In his “ Over the past two years a striking change has taken place in the boardrooms of greenhouse-gas producers: a growing number of large companies have announced commitments to achieve “net zero” emissions by 2050. These include the oil majors BP, Shell, and Total, the mining giant Rio Tinto, and the electricity supplier Southern Company. While such commitments are often described as “voluntary”—not mandated by government regulation—they were often adopted begrudgingly by executives and boards acquiescing to demands made by a coordinated group of their largest shareholders.

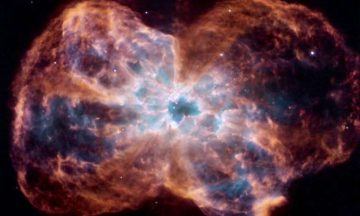

Over the past two years a striking change has taken place in the boardrooms of greenhouse-gas producers: a growing number of large companies have announced commitments to achieve “net zero” emissions by 2050. These include the oil majors BP, Shell, and Total, the mining giant Rio Tinto, and the electricity supplier Southern Company. While such commitments are often described as “voluntary”—not mandated by government regulation—they were often adopted begrudgingly by executives and boards acquiescing to demands made by a coordinated group of their largest shareholders. At the heart of every white dwarf star—the dense stellar object that remains after a star has burned away its fuel reserve of gases as it nears the end of its life cycle—lies a quantum conundrum: as white dwarfs add mass, they shrink in size, until they become so small and tightly compacted that they cannot sustain themselves, collapsing into a neutron star.

At the heart of every white dwarf star—the dense stellar object that remains after a star has burned away its fuel reserve of gases as it nears the end of its life cycle—lies a quantum conundrum: as white dwarfs add mass, they shrink in size, until they become so small and tightly compacted that they cannot sustain themselves, collapsing into a neutron star. Am I being reductive? All of narrative fiction, I’ve suggested, can be sorted into four grand categories. Each presents a rich world of feeling in which any number of stories can be told and positions established, but always in relation to, or rather, driven by, a distinct cluster of values and consequent emotions. My claim is that it really is worth being aware which of these worlds we are being drawn into. We read better. We know where we are. And what the dangers are.

Am I being reductive? All of narrative fiction, I’ve suggested, can be sorted into four grand categories. Each presents a rich world of feeling in which any number of stories can be told and positions established, but always in relation to, or rather, driven by, a distinct cluster of values and consequent emotions. My claim is that it really is worth being aware which of these worlds we are being drawn into. We read better. We know where we are. And what the dangers are. As we head into a tumultuous US election season, it is worth remembering that political parties can get trapped in partisan frameworks that cater to the loudest sections of their base, but which prevent them from appealing to a wider range of voters. Ideological litmus tests not only narrow appeal, but they cause politicians to pander, to disregard evidence, and to reject compromise in favor of rhetorical stridency. Social conservatives’ endlessly sputtering crusade over pornography is unusual in that it brings them into alliance with many radical feminists on the Left. Nevertheless, of the two main parties, it is the moral majoritarians in the Republican Party who have most frequently attempted to generate political capital by inveighing against pornography. This movement’s foundational moment was President Reagan’s Meese commission established to investigate the potential harms caused by pornography. The Meese Report, however, badly over-reached—even those who worry about the effects of pornography acknowledge it made

As we head into a tumultuous US election season, it is worth remembering that political parties can get trapped in partisan frameworks that cater to the loudest sections of their base, but which prevent them from appealing to a wider range of voters. Ideological litmus tests not only narrow appeal, but they cause politicians to pander, to disregard evidence, and to reject compromise in favor of rhetorical stridency. Social conservatives’ endlessly sputtering crusade over pornography is unusual in that it brings them into alliance with many radical feminists on the Left. Nevertheless, of the two main parties, it is the moral majoritarians in the Republican Party who have most frequently attempted to generate political capital by inveighing against pornography. This movement’s foundational moment was President Reagan’s Meese commission established to investigate the potential harms caused by pornography. The Meese Report, however, badly over-reached—even those who worry about the effects of pornography acknowledge it made  THE LATE, GREAT COMEDIAN

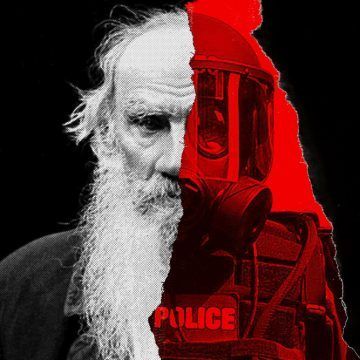

THE LATE, GREAT COMEDIAN Tolstoy was drawn to seekers, to characters perpetually in the throes of spiritual crisis; George Orwell described them as figures “struggling to make their souls.” Indeed, Tolstoy saw emergencies, personal and social, as necessary ruptures that could spark a deeper questioning of society and the beliefs that supported it. Of his own spiritual reawakening, captured in his memoir “A Confession” (1882), he described feeling as though the ground beneath him had collapsed. It is no wonder, then, that readers are finding new urgency in his work at a time when the racial and economic inequities revealed by Covid-19 and police killings have inspired unprecedented numbers of people to begin questioning some of this country’s foundational myths. With calls to defund the police, many are asking, for the first time in their lives, not just how our institutions function but whether they should exist at all.

Tolstoy was drawn to seekers, to characters perpetually in the throes of spiritual crisis; George Orwell described them as figures “struggling to make their souls.” Indeed, Tolstoy saw emergencies, personal and social, as necessary ruptures that could spark a deeper questioning of society and the beliefs that supported it. Of his own spiritual reawakening, captured in his memoir “A Confession” (1882), he described feeling as though the ground beneath him had collapsed. It is no wonder, then, that readers are finding new urgency in his work at a time when the racial and economic inequities revealed by Covid-19 and police killings have inspired unprecedented numbers of people to begin questioning some of this country’s foundational myths. With calls to defund the police, many are asking, for the first time in their lives, not just how our institutions function but whether they should exist at all. Lorna Finlayson in the New Left Review:

Lorna Finlayson in the New Left Review: