Julianne Chung in Psyche:

Julianne Chung in Psyche:

When I was 15, one of my closest friends died unexpectedly. Our physics teacher broke the news to me after I’d sat an exam, having wondered all the way through why my friend wasn’t there doing the same. I still don’t have the words to describe how I felt: it was something approaching shock, distress, disorientation. I didn’t know what to think, much less what to do. I spent many nights awake and many days in a daze.

Fifteen years later, when I was in graduate school, another friend died suddenly, a man I loved very much. I remember checking my phone and finding out, to my dismay, via text message. But while my initial response was much the same as before, there was a palpable difference in how I felt later on. While I was again surprised and saddened, I was much less disoriented than I’d been as a teenager. I could still think, and I could still get things done. It seemed to me that I’d become better at living with loss.

You might think that the reason for this difference is obvious – I was older, and I’d had more experience in coping with death. But raw experience alone isn’t enough: what matters more is whether we learn from experience. And learning from experience, especially an experience as difficult as the death of a loved one, can involve quite a lot. Among other things, it can involve creativity.

This claim might seem surprising. After all, creativity is often associated with the idea of a lone creative genius, an individual who not only excels at what they do, but also transforms the world in the process. Further, even if we don’t limit ourselves to romantic or heroic perspectives on the nature and value of creativity, it’s commonly thought that creativity at least aims at novelty or originality.

This way of thinking about creativity isn’t universal. The Zhuangzi (莊子), a classical Chinese philosophical and literary text, provides a different perspective.

More here.

Sara Tafakori in openDemocracy:

Sara Tafakori in openDemocracy: I

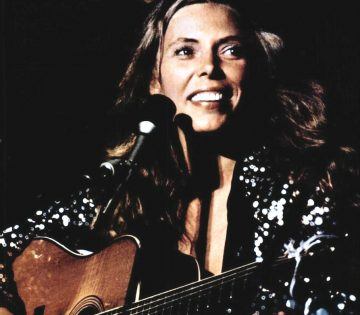

I “Next a lone spotlight shone on Odetta wearing a dark loose-fitting dress, and she began singing ‘Water Boy,’ or, rather, she unleashed it. Accompanying herself with her large National acoustic guitar, eyes closed, brows knitted in concentration, she brought the full tragedy and anger of chain gang life to bear.”

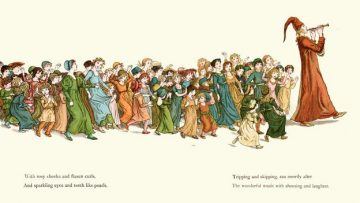

“Next a lone spotlight shone on Odetta wearing a dark loose-fitting dress, and she began singing ‘Water Boy,’ or, rather, she unleashed it. Accompanying herself with her large National acoustic guitar, eyes closed, brows knitted in concentration, she brought the full tragedy and anger of chain gang life to bear.” The tale in fact has survived for a very long time. Originating as medieval folklore, the story inspired a Goethe verse, Der Rattenfänger; a Grimm Brothers’ legend, The Children of Hamelin; and one of Robert Browning’s best-known poems, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. And although each writer tinkered with the story, the basics remained the same: the Piper was hired by Hamelin to rid the town of its plague of rats. Trailing after the hypnotic notes of the rat-catcher’s magical flute, the rodents politely filed through the city gates to their presumed doom.

The tale in fact has survived for a very long time. Originating as medieval folklore, the story inspired a Goethe verse, Der Rattenfänger; a Grimm Brothers’ legend, The Children of Hamelin; and one of Robert Browning’s best-known poems, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. And although each writer tinkered with the story, the basics remained the same: the Piper was hired by Hamelin to rid the town of its plague of rats. Trailing after the hypnotic notes of the rat-catcher’s magical flute, the rodents politely filed through the city gates to their presumed doom. When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed.

When President Donald Trump canceled a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris in 2018, he blamed rain for the last-minute decision, saying that “the helicopter couldn’t fly” and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true. Trump rejected the idea of the visit because he feared his hair would become disheveled in the rain, and because he did not believe it important to honor American war dead, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day. In a conversation with senior staff members on the morning of the scheduled visit, Trump said, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” In a separate conversation on the same trip, Trump referred to the more than 1,800 marines who lost their lives at Belleau Wood as “suckers” for getting killed. David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including

David Graeber, anthropologist and anarchist author of bestselling books on bureaucracy and economics including  Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.”

Quantum mechanics is more than a century old, but physicists still fight over what it means. Most of the hand wringing and knuckle cracking in their debates goes back to an assumption known as “realism.” This is the idea that science describes something—which we call “reality”—external to us, and to science. It’s a mode of thinking that comes to us naturally. It agrees well with our experience that the universe doesn’t seem to care what theories we have about it. Scientific history also shows that as empirical knowledge increases, we tend to converge on a shared explanation. This certainly suggests that science is somehow closing in on “the truth” about “how things really are.” Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger.

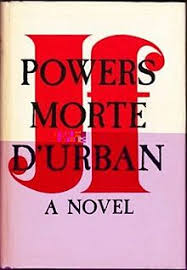

Donald Trump is so unlike most people, and so especially unlike anyone raised under a conventional moral framework, that he’s perpetually misdiagnosed. The words we see slapped on him most often, like “fascist” and “authoritarian,” nowhere near describe what he really is, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. It’s been proven across four years that Trump lacks the attention span or ambition required to implement a true dictatorial regime. He might not have a moral problem with the idea, but two minutes into the plan he’d leave the room, phone in hand, to throw on a robe and watch himself on Fox and Friends over a cheeseburger. Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford.

Like a lot of zealots, especially of the writerly sort, Powers was a perfectionist. His style, so clear and natural, came only with effort. His friend Sean O’Faolain liked to joke that Powers could spend a whole morning putting in a comma, and then the whole afternoon taking it out. “I don’t care to get a book out just to get a book out,” he wrote to a friend. “I’d rather make each one count—and in order to do that the way I nuts around, it takes time.” But it’s also true that Powers spent a great deal of time not writing. He insisted on going to a rented office every day—while Betty took care of cooking, cleaning, and raising the children—but, once there, he often just futzed around, reading the paper, rearranging the furniture, watching a ladybug crawl across an envelope. While in Ireland, he went to the races a lot and, like the writer in “Tinkers,” spent hours in auction houses bidding on useless stuff he couldn’t afford. W

W It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box.

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box. Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since

Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since  The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have

The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have  The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books.

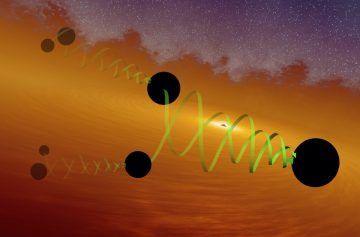

The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books.