Category: Recommended Reading

Christianity: Empathy Versus Evangelism

Rev. William Alberts in counterpunch:

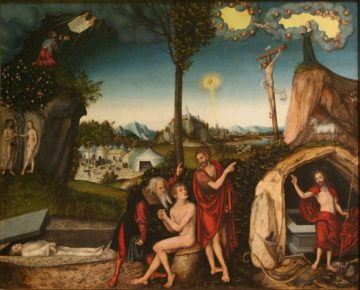

Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take.

Christianity has built-in contradictions. Certain Christians seek to empower people, while other Christians seek to gain power over them. Some Christians want to comfort people, while other Christians want to convert them. There are Christians who seek to love their neighbors as themselves, and other Christians want to make their neighbors like themselves. Certain Christians believe that people know what is best for themselves, while other Christians believe that they know exactly who and what is best for everyone. For some Christians, faith is about social justice and ethical behavior for other Christians, it is about theological orthodoxy. Certain Christians are committed to creating justice for people in this life, while other Christians stress justification by faith in Jesus Christ alone as the key to salvation in a future life. Not that evangelizing-motivated Christians do not comfort or empower or want justice for people, but they want it on their “Jesus is the Savior of the world” terms. Their unconscious predatory paternalism prevents them from experiencing and honoring other people’s reality and beliefs and negates any real mutually respectful democratic give and take.

Christianity’s built-in contradictions are found in its scripture. In Luke’s gospel, Jesus is recorded as saying that his mission was one of empathy: “the Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed me to “proclaim good news to the poor . . . liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, and to set at liberty those who are oppressed.” (4: 18,19) But the liberator was transformed into an evangelizer. In Matthew’s gospel, an assumed resurrected Jesus commissioned his disciples with, “All authority in heaven and on earth is given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you..” (28: 16-20) From identification with people to domination over people.

These contradictory biblical narratives are explained by a leap of three centuries after Jesus death.

More here.

Beyond the End of History

It is difficult to grasp the force of the prohibition on “presentism” without understanding the political backdrop against which it developed: the Cold War and the liberal internationalism endorsed by most Anglo-American historians. The profession’s current anxiety over presentism is a legacy of the Cold War university, which sought to resist the radicalism of a new generation of historians emerging in the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as push back against the postmodern turn of the 1970s. This inherited resistance inhibits a more thoughtful engagement with our current crises. We have been left strangely ill-equipped to confront history’s return.

Prohibitions against presentism are typically couched in philosophical or ethical terms. To commit the error of presentism, says the Yale American Studies scholar Wai Chee Dimock, is “to be blithely unaware of historical specificities, to project our values onto past periods without regard for the different norms then operative.” This is a kind of “narcissism,” she says, which “erases the historicity of texts.” Michel Rolph-Trouillot could claim, in 1995, that “academic historians tend to keep as far away as possible from historical controversies that most move the public of the day.”

More here.

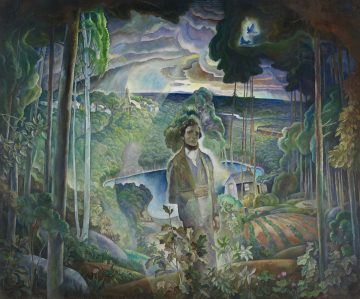

The Revolutionary Thoreau

R.H. Lossin at the NYRB:

The reason, perhaps, that Thoreau is not put off by the proximity of trains and farms is that he was not seeking solitude for solitude’s sake. He was attempting to extract himself from a society that he found deeply troubling. Thoreau does not begin his record of life alone with the naturalist observations that we have come to associate with him (and at which he excelled). Instead, Walden begins with trenchant critique of “progress.” Thoreau’s aversion to the rapid technological changes brought about by industrialization did not issue from a Romantic attachment to unspoiled Nature. In fact, he quite likes the sound of the trains, or is, at the very least, resigned to their permanent integration into the landscape. In the chapter on “Sounds,” he describes train whistles as well as birdcalls. “I watch,” he writes “the passage of the morning cars with the same feeling that I do the rising of the sun.”

more here.

Henry David Thoreau: A Life

The Mother Problem

Claire Jarvis at The Hedgehog Review:

The ideal mother, as countless novelists have known, is a dead one. It’s only when she is no longer living that the mother can function as a creature fully devoted to her child. Anything less than full, obliterating devotion is troubling: If she wasn’t willing to sacrifice everything—her relationship, her sleep, her career, her bodily integrity, her life—she should never have chosen to have a child. Spend a little time wallowing in the comments section of any online article about mothers, and you’ll see this formula. Motherhood is supposed to be all-encompassing and all-transforming. Except that now women are also required to maintain their sense of self—as manifested by their relationships, their bedtime routines, their jobs, their bodies—as a sign that they love their children enough to be good role models, exemplars of having it all. So, obviously: Mom is screwed from the start. She is never devoted enough to her child, never willing to transform herself entirely into her child’s helpmeet. She is also not separable enough—too worried about letting her child go, too occupied with her child’s life to live her own.

The ideal mother, as countless novelists have known, is a dead one. It’s only when she is no longer living that the mother can function as a creature fully devoted to her child. Anything less than full, obliterating devotion is troubling: If she wasn’t willing to sacrifice everything—her relationship, her sleep, her career, her bodily integrity, her life—she should never have chosen to have a child. Spend a little time wallowing in the comments section of any online article about mothers, and you’ll see this formula. Motherhood is supposed to be all-encompassing and all-transforming. Except that now women are also required to maintain their sense of self—as manifested by their relationships, their bedtime routines, their jobs, their bodies—as a sign that they love their children enough to be good role models, exemplars of having it all. So, obviously: Mom is screwed from the start. She is never devoted enough to her child, never willing to transform herself entirely into her child’s helpmeet. She is also not separable enough—too worried about letting her child go, too occupied with her child’s life to live her own.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Confused and Distraught

Again I am raging, I am in such a state by your soul that every

bond you bind, I break, by your soul.

I am like heaven, like the moon, like a candle by your glow; I am all

reason, all love, all soul, by your soul.

My joy is of your doing, my hangover of your thorn; whatever

side you turn your face, I turn mine, by your soul.

I spoke in error; it is not surprising to speak in error in this

state, for this moment I cannot tell cup from wine, by your soul.

I am that madman in bonds who binds the “divs”; I, the madman,

am a Solomon with the “divs”, by your soul.

Whatever form other than love raises up its head from my

heart, forthwith I drive it out of the court of my heart, by your soul.

Come, you who have departed, for the thing that departs

comes back; neither you are that, by my soul, nor I am that, by your soul.

Disbeliever, do not conceal disbelief in your soul, for I will recite

the secret of your destiny, by your soul.

Out of love of Sham-e Tabrizi, through wakefulness or

nightrising, like a spinning mote I am distraught, by your soul.

Rumi

from “Mystical Poems of Rumi 2” A. J. Arberry

The University of Chicago Press, 1991

Sunday, September 6, 2020

Frank Ramsey: A more human philosophy

Cheryl Misak in the TLS:

During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey.

During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey.

The 1920s were to be Ramsey’s only window in which to make his contributions. When the decade began, he was a seventeen year old, starting his mathematics undergraduate degree at Trinity College, Cambridge. Before he graduated, he had demolished John Maynard Keynes’s new theory of objective probability relations; made a valiant attempt at repairing a defect in Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica; translated Wittgenstein’s enormously difficult Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus from German to English; and published a critical notice of the Tractatus for the journal Mind, which still stands as one of the most challenging commentaries of that influential book.

This was a stunning run for an undergraduate. Keynes was building an economics empire at King’s and he knew a good thing when he saw it. In an impressive show of administrative skill and sleight of hand, he snapped up the young prodigy before Trinity could blink.

More here.

How Close Are Computers to Automating Mathematical Reasoning?

Stephen Ornes in Quanta:

In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic, reportedly made a sweeping prediction that continues to excite and irritate mathematicians — that “at some unspecified future time, mathematicians would be replaced by computers.” Cohen, legendary for his daring methods in set theory, predicted that all of mathematics could be automated, including the writing of proofs.

In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic, reportedly made a sweeping prediction that continues to excite and irritate mathematicians — that “at some unspecified future time, mathematicians would be replaced by computers.” Cohen, legendary for his daring methods in set theory, predicted that all of mathematics could be automated, including the writing of proofs.

A proof is a step-by-step logical argument that verifies the truth of a conjecture, or a mathematical proposition. (Once it’s proved, a conjecture becomes a theorem.) It both establishes the validity of a statement and explains why it’s true. A proof is strange, though. It’s abstract and untethered to material experience. “They’re this crazy contact between an imaginary, nonphysical world and biologically evolved creatures,” said the cognitive scientist Simon DeDeo of Carnegie Mellon University, who studies mathematical certainty by analyzing the structure of proofs. “We did not evolve to do this.”

Computers are useful for big calculations, but proofs require something different.

More here.

Shun the autocrats, re-embrace human rights

Ken Roth in The Dallas Morning News:

The U.S. government has never been a consistent promoter of human rights — other interests were often prioritized — but when it did act, it could be powerful. Yet U.S. influence on human rights has plummeted under President Donald Trump. If Joe Biden assumes the presidency, he will need to oversee a major transformation if he wants the U.S. government to be a credible human rights voice.

The U.S. government has never been a consistent promoter of human rights — other interests were often prioritized — but when it did act, it could be powerful. Yet U.S. influence on human rights has plummeted under President Donald Trump. If Joe Biden assumes the presidency, he will need to oversee a major transformation if he wants the U.S. government to be a credible human rights voice.

It will not be enough simply to revert to the (often inadequate) policies of four years ago. The world has changed since then, with a pandemic, the further rise of China — which recently sanctioned me and 10 other U.S citizens for our rights work on Hong Kong — and growing global awareness of racism, inequality and other injustices that leave so many people behind. U.S. policy will need to adjust.

It is harder to contemplate major changes from a second Trump administration. But even Trump, once he no longer needs to appeal to his base for re-election, may be more willing to contemplate his global image and place in history. Or perhaps Congress can succeed in exerting pressure on him to reassess his most detrimental human rights policies.

More here.

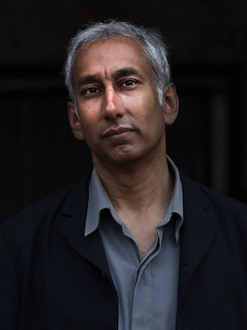

Cultivating Care: An Interview with Asad Raza

Hannah Carroll Harris in Berlin Art Link:

Asad Raza’s expansive cross-disciplinary practice defies categorization. Situated somewhere between performance, installation and curation, its elusiveness can be attributed to many factors. Primary to these is the fact that Raza’s work rejects the rigid prescriptiveness that these disciplines often demand. Rather, his open-ended, site-specific installations supply fertile ground for interaction, ideas and communities to develop. In his piece ‘Absorption’, currently on view at Gropius Bau as part of ‘Down to Earth’, this is quite literally the case. Twenty tons of artificial neosoil have been installed within the gallery space, cared for by a team of “cultivators” who tend to the soil, raking it, testing its PH levels and gifting it to visitors to nurture their own gardens. Here, both the soil and its cultivators act as a conduit for conversation and community.

Asad Raza’s expansive cross-disciplinary practice defies categorization. Situated somewhere between performance, installation and curation, its elusiveness can be attributed to many factors. Primary to these is the fact that Raza’s work rejects the rigid prescriptiveness that these disciplines often demand. Rather, his open-ended, site-specific installations supply fertile ground for interaction, ideas and communities to develop. In his piece ‘Absorption’, currently on view at Gropius Bau as part of ‘Down to Earth’, this is quite literally the case. Twenty tons of artificial neosoil have been installed within the gallery space, cared for by a team of “cultivators” who tend to the soil, raking it, testing its PH levels and gifting it to visitors to nurture their own gardens. Here, both the soil and its cultivators act as a conduit for conversation and community.

With a background in film-making, Raza composes situations in which to explore our relations with non-human living beings, and each other, with a view to thinking about how we can foster new ways of approaching and caring for these relationships. Whether through a fully-functioning tennis court installed in a 16th Century Milanese church; 26 young flowering trees and their caretakers at the Whitney Biennial; or tons of artificial soil in Sydney and Berlin, his works far exceed the bounds of the walls in which they are situated. We spoke to Raza about this radiating effect, the role of agency and new ways of thinking about care and kinship in the creative community.

More here.

Darkening Shadows

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

All the facts are already known, and against each fact the supporters of Donald Trump have woven careful rationalizations. The truths are ugly, and so they have been festooned with kitschy trappings; some fall from the lips of a First Lady who speaks of bringing Americans together in a dress that costs about what the average female wage-earner in the United States makes in a month. I imagine the homes of Trump supporters as staging areas for transforming these ugly truths: the 186,000 Covid-19 death toll wrapped in duct tape and Trump’s yellow ties until it cannot be seen, and set down in a corner. Also in that dark corner we see factual information about Kamala Harris’s birthplace in Oakland, California, rejected—her birth certificate obscured with black lettering that shouts foreigner, “anchor baby,” alien, spy, and bitch. In this way, millions of factories of false facts are slapped-and-dashed together in the homes of Trump’s supporters to create a world that accords with the words of their leader. There is no arsenal of truth that can penetrate into their homes or their hearts.

All the facts are already known, and against each fact the supporters of Donald Trump have woven careful rationalizations. The truths are ugly, and so they have been festooned with kitschy trappings; some fall from the lips of a First Lady who speaks of bringing Americans together in a dress that costs about what the average female wage-earner in the United States makes in a month. I imagine the homes of Trump supporters as staging areas for transforming these ugly truths: the 186,000 Covid-19 death toll wrapped in duct tape and Trump’s yellow ties until it cannot be seen, and set down in a corner. Also in that dark corner we see factual information about Kamala Harris’s birthplace in Oakland, California, rejected—her birth certificate obscured with black lettering that shouts foreigner, “anchor baby,” alien, spy, and bitch. In this way, millions of factories of false facts are slapped-and-dashed together in the homes of Trump’s supporters to create a world that accords with the words of their leader. There is no arsenal of truth that can penetrate into their homes or their hearts.

It is like an abusive relationship. So many of us have fallen, despite ourselves, for terrible people. Now half the country is in the thrall of an abusive, domineering sadist, subject to manic moods and vicious beatings and a seemingly unending appetite for chaos. This has gone on for three and a half years. Abused women, we know, are at the greatest risk of being killed when they try to leave. Donald Trump, like all the cowardly and manipulative abusers before him, knows this. The only difference is that he will not save his wrath for those he is used to abusing but for all of us, for all of America. Trump will raze all of Rome to the ground before the Visigoths arrive. If Trump cannot have America, I fear, there will not be any America left to be had.

More here.

Stealing from the Saracens – a long-overlooked cultural exchange

Rowan Moore in The Guardian:

In 2019, a survey asked 3,624 Americans if Arabic numerals should be taught in school. An affronted 56% – and 72% of Republican respondents – said no. Only 29% said yes. The nos didn’t seem to know that Arabic numerals are the things they type with the keypads of their phones.

In 2019, a survey asked 3,624 Americans if Arabic numerals should be taught in school. An affronted 56% – and 72% of Republican respondents – said no. Only 29% said yes. The nos didn’t seem to know that Arabic numerals are the things they type with the keypads of their phones.

Something similar has happened with architecture. You can read titans of art history such as Kenneth Clark or Nikolaus Pevsner, who took upon themselves the task of defining European civilisation, and barely find a mention of the Great Mosque of Córdoba or the Alhambra in Granada – extraordinary and important works of architecture that are unarguably located in Europe. It’s a breathtaking omission. Acccording to Diana Darke, the thing called “gothic”, versions of which (Notre-Dame, Houses of Parliament) have been claimed as the national style of several northern European countries, which theorists such as John Ruskin and Augustus Pugin saw as quintessentially Christian, is deeply indebted to Arab and Muslim builders in the centuries following the life of Muhammad.

Pointed arches, ribbed vaults, spires, campaniles, rose windows, certain types of dome construction, variants of stained glass, the machicolations of castles, twin-towered cathedral fronts, possibly the cloister – all can be traced, says Darke, to older buildings in the Middle East and southern Spain. She argues that the trefoil arch – a three-lobed shape often used on churches as a symbol of the Trinity – is also Arab in origin. Through a hilariously mistaken belief that the Muslim Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem was Solomon’s Temple, a number of churches copied it.

More here.

Aldir Blanc (1946 – 2020)

Salome Bey (1933 – 2020)

Sunday Poem

We Sinful Women

It is we sinful women

who are not awed by the grandeur of those who wear gowns

who don’t sell our lives

who don’t bow our heads

who don’t fold our hands together.

It is we sinful women

while those who sell the harvests of our bodies

become exalted

become distinguished

become the just princes of the material world.

It is we sinful women

who come out raising the banner of truth

up against barricades of lies on the highways

who find stories of persecution piled on each threshold

who find that tongues which could speak have been severed.

It is we sinful women.

Now, even if the night gives chase

these eyes shall not be put out.

For the wall which has been razed

don’t insist now on raising it again.

It is we sinful women

who are not awed by the grandeur of those who wear gowns

who don’t sell our bodies

who don’t bow our heads

who don’t fold our hands together.

by Rukhsana Ahmad

from: We Sinful Women: Contemporary Urdu Feminist Poetry

publisher: The Women’s Press Ltd, London, 1991

Original editor’s note: This seminal poem was both a revelation and incendiary at the time it was written. It is a declaration of the independence of women who did not subscribe to societal and cultural norms. These norms imposed on women are oppressive and confining, and for the most part still exist today in Pakistan, if not in even greater force.

Joe Ruby (1933 – 2020)

Saturday, September 5, 2020

Chris Bertram and Kenan Malik Debate “White Privilege”

Over at Crooked Timber, first Chris Bertram:

Over at Crooked Timber, first Chris Bertram:

The term “white privilege” has been getting a lot of play and a lot of pushback recently, for example, from Kenan Malik in this piece and there are some parallels in the writing of people like Adolph Reed who want to stress class-based solidarity over race. Often it isn’t clear what the basic objection from “class” leftists to the concept of “white privilege” is. Sometimes the objection seems to be a factual one: that no such thing exists or that insofar as there is something, then it is completely captured by claims about racism, so that the term “white privilege” is redundant. Alternatively, the objection is occasionally strategic or pragmatic: the fight for social justice requires an alliance that crosses racial and other identity boundaries and terms like “white privilege” sow division and make that struggle more difficult. These objections are, though, logically independent of one another: “white privilege” could be real, but invoking it could be damaging to the struggle; or it could be pragmatically useful for justice even if somewhat nebulous and explanatorily empty.

More here.

Kenan Malik:

In the first post, Chris argues that “the ‘white privilege’ claim sits best with a certain sort of metaphysics of the person, such that individuals have a range of characteristics, some of which are more natural and others more social, that confer a competitive advantage or disadvantage in a given environment, where that environment is constituted by a range of elements, including demographics, institutions, cultural practices, individual attitudes, and so forth.”

But he also acknowledges that “I’m not establishing that, as a matter of fact, “white privilege” in the form I describe is a real thing, although I believe that it is”. It is difficult to see, though, how one can have a debate about whether “white privilege” is a meaningful category without have first established whether it is “a real thing”. It is possible to have an abstract debate about whether such a phenomenon could exist, but not to critique those who challenge the concept as inchoate in reality. Chris, in common with many proponents of the “white privilege” thesis, takes as given that which has to be demonstrated.

More here.

Germany finds it hard to love Hegel 250 years after his birth

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

In March 1807, aged 36, a towering giant of German philosophy was struggling to come to terms with a career dip.

With an illegitimate son to support and a patrimonial inheritance run dry, George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel had chucked in an unpaid academic post and accepted a job as an editor at a local newspaper in Bamberg, where he was compiling reports on royal boar hunts. Only a newly acquired coffee percolator offered brief caffeinated thrills.

To make things worse, friends got in touch with feedback on his recently completed 600-page magnus opus, The Phenomenology of the Spirit. They found it hard going.

The man Bertrand Russell later described as “the hardest to understand of the great philosophers” responded with a rare moment of self-doubt. Sometimes, he conceded, it was “easier to be sublimely unintelligible than to be comprehensible in a simple way”.

More here.

On Witness and Respair: A Personal Tragedy Followed by Pandemic

Jesmyn Ward in Vanity Fair:

Jesmyn Ward in Vanity Fair:

My Beloved died in January. He was a foot taller than me and had large, beautiful dark eyes and dexterous, kind hands. He fixed me breakfast and pots of loose-leaf tea every morning. He cried at both of our children’s births, silently, tears glazing his face. Before I drove our children to school in the pale dawn light, he would put both hands on the top of his head and dance in the driveway to make the kids laugh. He was funny, quick-witted, and could inspire the kind of laughter that cramped my whole torso. Last fall, he decided it would be best for him and our family if he went back to school. His primary job in our household was to shore us up, to take care of the children, to be a househusband. He traveled with me often on business trips, carried our children in the back of lecture halls, watchful and quietly proud as I spoke to audiences, as I met readers and shook hands and signed books. He indulged my penchant for Christmas movies, for meandering trips through museums, even though he would have much preferred to be in a stadium somewhere, watching football. One of my favorite places in the world was beside him, under his warm arm, the color of deep, dark river water.

In early January, we became ill with what we thought was flu. Five days into our illness, we went to a local urgent care center, where the doctor swabbed us and listened to our chests. The kids and I were diagnosed with flu; my Beloved’s test was inconclusive. At home, I doled out medicine to all of us: Tamiflu and Promethazine. My children and I immediately began to feel better, but my Beloved did not. He burned with fever. He slept and woke to complain that he thought the medicine wasn’t working, that he was in pain. And then he took more medicine and slept again.

Two days after our family doctor visit, I walked into my son’s room where my Beloved lay, and he panted: Can’t. Breathe.

More here.

Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”

Scholars and nonscholars alike are struggling to make sense of what is happening today. The public is turning to the past — through popular podcasts, newspapers, television, trade books and documentaries — to understand the blooming buzzing confusion of the present. Historians are being called upon by their students and eager general audiences trying to come to grips with a world again made strange. But they face an obstacle. The Anglo-American history profession’s cardinal sin has been so-called “presentism,” the illicit projection of present values onto the past. In the words of the Cambridge University historian Alexandra Walsham, “presentism … remains one of the yardsticks against which we continue to define what we do as historians.”