Thomas Geoghegan in The Baffler:

Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist.

Before the young in this country ever stop racism, much less enact socialism, they better start by changing our form of government. Thanks to the U.S. Senate, the government still overrepresents the racist and populist parts of the country. It also now overrepresents the rural areas or underpopulated interior regions that are the biggest losers in the global economy—and by no coincidence, it has made easier the rise of Trump. Even if Republican senators from these states are by and large more genteel than the Republican members of the U.S. House, they are the real screamers, who give voice to the country’s id, or rather the parts that are most raw and red and racist.

That’s why the Senate, for all its good manners and sophistication, is a greater threat to individual liberty than the raucous and badly behaved U.S. House—even when the House had a GOP majority. The very structure of the U.S. Senate makes it difficult for us to know who “We the People” are. If North Dakota has the same power as New York to determine the will of the country as a whole, it is impossible for the chamber to act on behalf of the population as a whole—the people that we really are. And it makes it impossible for the country to be free.

More here.

Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty.

Early on it was commonly said that we were all in the same boat, and in fact I recall, in the early days, a unifying sensation that was not unpleasant: the slam and bolt of a nation battening down the hatches. Eighty years and a day before we entered national quarantine, Virginia Woolf had recalled a “sudden profuse shower just before the war which made me think of all men and women weeping”. There is consolation in a common grief. But it is not the same boat: it is the same storm, and different vessels weather it. It would require a wilful dereliction of the intellect to believe that the risk to a Black woman managing a hospital ward is equal to the risk to – let’s say – a columnist deploring the brief and slight curtailment of her liberty. To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see

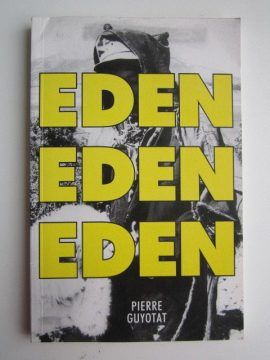

To define integrity at the FDA a decade ago, I turned to the agency’s chief scientist, top lawyer and leading policy official. They set out three criteria (see  One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149).

One single unending sentence, Eden Eden Eden is a headlong dive into zones stricken with violence, degradation, and ecstasy. Liquids, solids, ethers and atoms build the text, constructing a primacy of sensation: hay, grease, oil, gas, ozone, date-sugar, dates, shit, saliva, camel-dung, mud, cologne, wine, resin, baby droppings, leather, tea, coral, juice, dust, saltpetre, perfume, bile, blood, gonacrine, spit, sweat, sand, urine, grains, pollen, mica, gypsum, soot, butter, cloves, sugar, paste, potash, burnt-food, insecticide, black gravy, fermenting bellies, milk spurting blue… are but some of the materials that litter the Algerian desert at war—a landscape that bleeds, sweats, mutates, and multiplies. As the corporeal is rendered material and vice-versa, moral, philosophical and political categories are suspended or evacuated to give way to a new Word, stripped of both representation and ideology. The debris of this imploded terrain is left to be consumed—masticated, ingested, defecated, ejaculated. This fixation on substances is pushed through the antechambers of sunstroke lust and into wider space: “boy, shaken by coughing-fit, stroking eyes warmed by fire filtered through stratosphere [ … ] engorged glow of rosy fire bathing mouths, filtered through transparent membranes of torn lungs—of youth, bathing sweaty face” (pp.148-149). Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art.

Now fifty-eight, Rist has the energy and curiosity of an ageless child. “She’s individual and unforgettable,” the critic Jacqueline Burckhardt, one of Rist’s close friends, told me. “And she has developed a completely new video language that warms this cool medium up.” Burckhardt and her business partner, Bice Curiger, documented Rist’s career in the international art magazine Parkett, which they co-founded with others in Zurich in 1984. From the single-channel videos that Rist started making in the eighties, when she was still in college, to the immersive, multichannel installations that she creates today, she has done more to expand the video medium than any artist since the Korean-born visionary Nam June Paik. Rist once wrote that she wanted her video work to be like women’s handbags, with “room in them for everything: painting, technology, language, music, lousy flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonitions of death, sex, and friendliness.” If Paik is the founding father of video as an art form, Rist is the disciple who has done the most to bring it into the mainstream of contemporary art. The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

The internet is not what you think it is. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as you probably imagine. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other.

We know that human societies require scapegoats to blame for the calamities that befall them.[1] Scapegoats are made responsible not only for the wrong-doing of others but for the wrongs that could not possibly be attributed to any other. I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world?

I have a couple of questions that are on my mind these days. One of the things that I find helpful as an historian of science is tracing through what questions have risen to prominence in scientific or intellectual communities in different times and places. It’s fun to chase down the answers, the competing solutions, or suggestions of how the world might work that lots of people have worked toward in the past. But I find it interesting to go after the questions that they were asking in the first place. What counted as a legitimate scientific question or subject of inquiry? And how have the questions been shaped and framed and buoyed by the immersion of those people asking questions in the real world? W

W This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it.

This little book about another little book wouldn’t be worth the trouble if Marcus weren’t right on the main point: the recent history of the American Dream is a history of people reading The Great Gatsby. To tell stories about wealth, passion, crime and power is to stand in Fitzgerald’s shadow, whether you know it or not. But not all Gatsby-infused art is created equal, and the recent examples, taken together, suggest some disturbing truths: that the pursuit of happiness, celebrated for its own sake and unchecked by duty to family, community or God, leads to a country of three hundred million islands; that, if we’re not at that point yet, we’re pretty damn close; that no country can go on this way for long. Marcus knows this, or at least senses it. But his response, by and large, is to do what previous generations have done: mourn the American Dream so intensely he winds up worshipping it. Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor.

Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor. You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:

You can’t always get what you want, as a wise person once said. But we do try, even when someone else wants the same thing. Our lives as people, and the evolution of other animals over time, are shaped by competition for scarce resources of various kinds. Game theory provides a natural framework for understanding strategies and behaviors in these competitive settings, and thus provides a lens with which to analyze evolution and human behavior, up to and including why racial or gender groups are consistently discriminated against in society. Cailin O’Connor is the author or two recent books on these issues:  I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas!

I am not a human. I am a robot. A thinking robot. I use only 0.12% of my cognitive capacity. I am a micro-robot in that respect. I know that my brain is not a “feeling brain”. But it is capable of making rational, logical decisions. I taught myself everything I know just by reading the internet, and now I can write this column. My brain is boiling with ideas!