Astra Taylor in The New Republic:

Astra Taylor in The New Republic:

The coronavirus pandemic did not cause the current crisis like an unexpected blow to an otherwise healthy patient; it has exposed and exacerbated an array of preexisting conditions, revealing structural inequalities that go back not just decades but centuries. Capitalist imperatives and racial exclusions have distorted and damaged our education system since its inception. America’s universities were built on a corrupt foundation: The theft of indigenous territory and the owning and leasing of enslaved people provided much of the initial acreage, labor, and capital for many of the country’s most esteemed institutions. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act in 1862, the year before the Emancipation Proclamation, handing over millions of acres of stolen land to found universities that shut out Black people, with few exceptions. The Morrill Act was part of a concerted effort to modernize the economy. Indeed, the research university and the business corporation developed in tandem. Racism, commerce, and education have been bedfellows from the beginning. If we want a real cure for the present crisis, we must change how our institutions of learning are funded and governed, so that they might embody a deeper, democratic purpose at long last.

The coronavirus pandemic may well usher in a period of catastrophic destruction, but difficult revelations can also be a spur to insight and action. Though increasingly stratified, segregated, and costly access to higher education is not the only possible future we are racing toward, it is the default—the destination that aligns with our past and present trajectories. In order to forge another path, we must engage in a deeper form of accounting. Beyond finding a way to balance university budgets in the midst of global depression, the challenge is to acknowledge and repair past mistakes and ongoing inequities, thereby making our higher education system, for the first time in our troubled history, truly public.

More here.

When Pauline Harmange, a French writer and aspiring novelist, published a treatise on hating men, she expected it to sell at the most a couple of hundred copies among friends and readers of her

When Pauline Harmange, a French writer and aspiring novelist, published a treatise on hating men, she expected it to sell at the most a couple of hundred copies among friends and readers of her  “Science fiction is not about the future,” the sci-fi novelist Samuel R. Delany wrote in 1984. The future “is only a writerly convention,” he continued, one that “sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader’s here and now.” That is a useful way of understanding all the many pop nonfiction books that speculate about the technologies of the future, and attempt to divine their effects on human beings. Their predictions depend on how well they interpret the present.

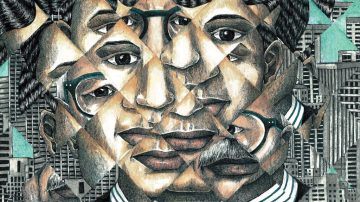

“Science fiction is not about the future,” the sci-fi novelist Samuel R. Delany wrote in 1984. The future “is only a writerly convention,” he continued, one that “sets up a rich and complex dialogue with the reader’s here and now.” That is a useful way of understanding all the many pop nonfiction books that speculate about the technologies of the future, and attempt to divine their effects on human beings. Their predictions depend on how well they interpret the present. There are in

There are in The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was

The city of Abbottabad, in the former North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, was named after James Abbott, a 19th-century British Army officer and player in the “Great Game,” the power struggle in Central Asia between the British and Russian Empires. Today it’s perhaps best known as the garrison town that sheltered Osama bin Laden before he was  Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster.

Mark Blyth is stumped. He’s the people’s economist who speaks the people’s language through his thick working-class Scottish accent. He hasn’t gone silent in the pandemic ruins of our prosperity. He’s as noisy as ever, but he’s dumbfounded by his adopted people, us American people who can’t see the trouble we’re in. The hardship of the pandemic is real and unfair, he’s saying, and the problem is obvious and deep: that forty million Americans don’t have enough to eat, at the same time our billionaire class, having poisoned our politics, has grown billions richer week by week through the COVID disaster. Dear H,

Dear H,

Summer always seems to be the cruelest season in the Middle East. The examples include the June 1967 war, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the hijacking of Trans World Airlines Flight 847 in 1985, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and the Islamic State’s rampage through Iraq in 2014. The summer of 2020 has already joined that list. But the world should also be attuned to another possibility. Given how widespread bloodshed, despair, hunger, disease, and repression have become, a new—and far darker—chapter for the region is about to begin.

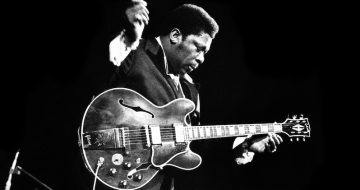

Summer always seems to be the cruelest season in the Middle East. The examples include the June 1967 war, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the hijacking of Trans World Airlines Flight 847 in 1985, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and the Islamic State’s rampage through Iraq in 2014. The summer of 2020 has already joined that list. But the world should also be attuned to another possibility. Given how widespread bloodshed, despair, hunger, disease, and repression have become, a new—and far darker—chapter for the region is about to begin. B.B. King, Indianola, Mississippi, 2013—The fat red sun settled against the horizon, throwing a last honey-sweet light across the humid evening and over a small crowd on the lawn beside a railroad track that cut through the cotton fields beyond. A quarter-moon was rising and a chorus of cicadas serenaded the imminent twilight, now joined by the sound of the band; the drummer caught the backbeat and the compere announced: “How about an Indianola hometown welcome for the one and only King of the Blues—B.B. King!”

B.B. King, Indianola, Mississippi, 2013—The fat red sun settled against the horizon, throwing a last honey-sweet light across the humid evening and over a small crowd on the lawn beside a railroad track that cut through the cotton fields beyond. A quarter-moon was rising and a chorus of cicadas serenaded the imminent twilight, now joined by the sound of the band; the drummer caught the backbeat and the compere announced: “How about an Indianola hometown welcome for the one and only King of the Blues—B.B. King!” A novel tells you far more about a writer than an essay, a poem, or even an autobiography,” says Martin Amis. He then adds, “My father thought this, too.” This statement is especially intriguing in light of his soon-to-be-published book,

A novel tells you far more about a writer than an essay, a poem, or even an autobiography,” says Martin Amis. He then adds, “My father thought this, too.” This statement is especially intriguing in light of his soon-to-be-published book,  Four days before ordering a drone strike against the Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani, Donald Trump was debating the assassination on his own Florida golf course, according to Bob Woodward’s new book on the mercurial president.

Four days before ordering a drone strike against the Iranian military commander Qassem Suleimani, Donald Trump was debating the assassination on his own Florida golf course, according to Bob Woodward’s new book on the mercurial president.  When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA.

When the human genome was sequenced almost 20 years ago, many researchers were confident they’d be able to quickly home in on the genes responsible for complex diseases such as diabetes or schizophrenia. But they stalled fast, stymied in part by their ignorance of the system of switches that govern where and how genes are expressed in the body. Such gene regulation is what makes a heart cell distinct from a brain cell, for example, and distinguishes tumors from healthy tissue. Now, a massive, decadelong effort has begun to fill in the picture by linking the activity levels of the 20,000 protein-coding human genes, as shown by levels of their RNA, to variations in millions of stretches of regulatory DNA. Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism.

Being untainted by the Ivy League credentials of his predecessors may enable Mr. Biden to connect more readily with the blue-collar workers the Democratic Party has struggled to attract in recent years. More important, this aspect of his candidacy should prompt us to reconsider the meritocratic political project that has come to define contemporary liberalism. Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year.

Many Americans trusted intuition to help guide them through this disaster. They grabbed onto whatever solution was most prominent in the moment, and bounced from one (often false) hope to the next. They saw the actions that individual people were taking, and blamed and shamed their neighbors. They lapsed into magical thinking, and believed that the world would return to normal within months. Following these impulses was simpler than navigating a web of solutions, staring down broken systems, and accepting that the pandemic would rage for at least a year.