Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka):

Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka):

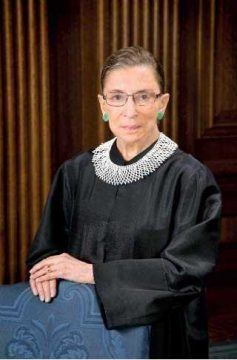

A diminutive, shy person with head bowed down walked into the room. She walked slowly but with a purposive step. When she began the class her voice was just above a whisper and her words were accompanied by long pauses as we strained to listen. This was 1976 and I was enrolled in the class of Professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg as she began her pioneering course on sex-based discrimination and the law.

As a South Asian I was used to vibrant and colourful women leaders. Ginsburg was anything but. With a cold, piercing, powerful, intellect, she showed us how to dissect arguments, plan a cohesive strategy and win the battle. She was all about the analysis, the details and the hard work. Her main area of interest in the law was Civil Procedure, the rules and processes of the legal system. I usually fell asleep during those classes but it was Ginsburg who convinced me that if you are going to be a human rights lawyer, first master the procedure. Your passion will guide the substance.

More here.

I

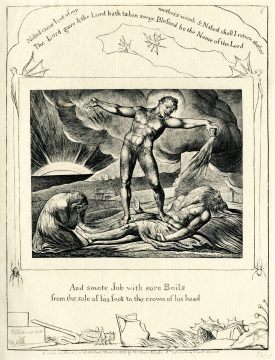

I I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy.

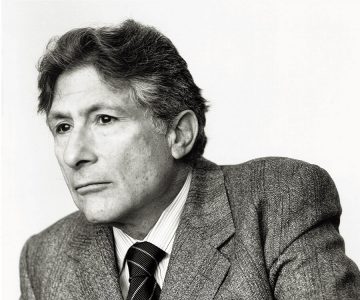

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy. My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease.

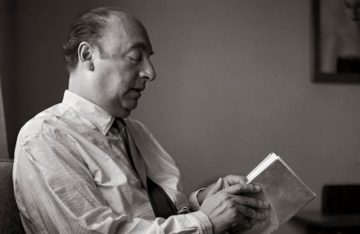

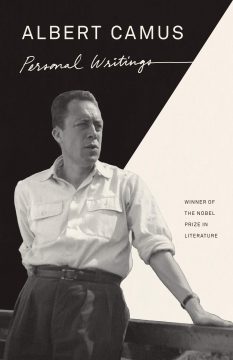

My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease. In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity.

In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity. Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.”

Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.” With a presidential election less than five weeks away, and a new term at the U.S. Supreme Court just over a week away, President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court. The funeral for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose seat he would be filling after she died last week, is not scheduled until next week, but President Trump and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible. The announcement is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. But if the nomination is successful, it could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century, securing a two-thirds majority of conservative jurists that could advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations at a speed and scope of its choosing.

With a presidential election less than five weeks away, and a new term at the U.S. Supreme Court just over a week away, President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court. The funeral for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose seat he would be filling after she died last week, is not scheduled until next week, but President Trump and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible. The announcement is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. But if the nomination is successful, it could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century, securing a two-thirds majority of conservative jurists that could advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations at a speed and scope of its choosing. If anyone knows about going fungal, it’s Paul Stamets. I have often wondered whether he has been infected with a fungus that fills him with mycological zeal—and an irrepressible urge to persuade humans that fungi are keen to partner with us in new and peculiar ways. I went to visit him at his home on the west coast of Canada. The house is balanced on a granite bluff, looking out to sea. The roof is suspended on beams that look like mushroom gills. A Star Trek fan since the age of 12, Stamets christened his new house Starship Agarikon—agarikon is another name for Laricifomes officinalis, a medicinal wood-rotting fungus that grows in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

If anyone knows about going fungal, it’s Paul Stamets. I have often wondered whether he has been infected with a fungus that fills him with mycological zeal—and an irrepressible urge to persuade humans that fungi are keen to partner with us in new and peculiar ways. I went to visit him at his home on the west coast of Canada. The house is balanced on a granite bluff, looking out to sea. The roof is suspended on beams that look like mushroom gills. A Star Trek fan since the age of 12, Stamets christened his new house Starship Agarikon—agarikon is another name for Laricifomes officinalis, a medicinal wood-rotting fungus that grows in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

If a COVID-19 vaccine went on the market before Election Day,

If a COVID-19 vaccine went on the market before Election Day,  C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

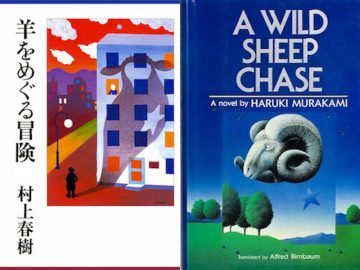

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal? On May 10, 1989, Haruki Murakami’s editor at Kodansha International, Elmer Luke, sent Murakami a fax reporting on the sale of U.S. paperback rights to A Wild Sheep Chase (to Plume for fifty-five thousand dollars) and asking him to take part in the promotional activities that were scheduled in New York that fall. Murakami declined. Several months later, Luke and Murakami met in person for the first time in Tokyo (together with another editor from KI), and on August 14, just three days before a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase arrived at the Murakamis’ home, Luke again asked Murakami to join him in New York. Murakami once again declined. On September 24, Luke asked again, saying that Murakami’s translator Alfred Birnbaum had become unable to attend, and that they had also managed to arrange an interview with the New York Times. Murakami finally relented.

On May 10, 1989, Haruki Murakami’s editor at Kodansha International, Elmer Luke, sent Murakami a fax reporting on the sale of U.S. paperback rights to A Wild Sheep Chase (to Plume for fifty-five thousand dollars) and asking him to take part in the promotional activities that were scheduled in New York that fall. Murakami declined. Several months later, Luke and Murakami met in person for the first time in Tokyo (together with another editor from KI), and on August 14, just three days before a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase arrived at the Murakamis’ home, Luke again asked Murakami to join him in New York. Murakami once again declined. On September 24, Luke asked again, saying that Murakami’s translator Alfred Birnbaum had become unable to attend, and that they had also managed to arrange an interview with the New York Times. Murakami finally relented.