Kevin P. Donovan in the Boston Review:

E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.”

E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.”

It did not take Marx’s later dictum that workers are free in a “double sense”—to work or to starve—to explain the distinction between income and wealth to the silk weaver. Wealth is an asset, providing a buffer against unexpected shocks in the short term and economic security in the long run. On the other hand, labor (the means to one’s income) expires as soon as it stops. There is no way to store labor—to “bottle it” or “lay it up in salt”—thus working people navigate a series of urgent demands on their time and well-being.

More here.

“Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it.

“Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it. Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist.

Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist. The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories.

The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories. What does the worst debate in American history look like? It looks like the debate that took place on Tuesday night between President

What does the worst debate in American history look like? It looks like the debate that took place on Tuesday night between President  China’s long love affair with England’s greatest consulting detective is a mystery worth solving. The BBC hit show Sherlock, which ran from 2010-17, proved a smash with Chinese viewers: 4.72 million viewers watched one episode, eager to find out how Holmes dodged death after plunging off the roof of London’s St. Bart’s Hospital at the end of the previous season. Weibo, China’s Twitter, was filled with chatter about the show by fans of “Curly Fu” and “Peanut” (the nicknames given by Chinese fans to Holmes and Watson, because they sound like the Chinese pronunciation of their names).

China’s long love affair with England’s greatest consulting detective is a mystery worth solving. The BBC hit show Sherlock, which ran from 2010-17, proved a smash with Chinese viewers: 4.72 million viewers watched one episode, eager to find out how Holmes dodged death after plunging off the roof of London’s St. Bart’s Hospital at the end of the previous season. Weibo, China’s Twitter, was filled with chatter about the show by fans of “Curly Fu” and “Peanut” (the nicknames given by Chinese fans to Holmes and Watson, because they sound like the Chinese pronunciation of their names). Two and a half years ago, MIT entered into a research agreement with startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems to develop a next-generation fusion research experiment, called SPARC, as a precursor to a practical, emissions-free power plant.

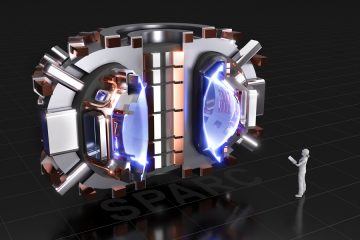

Two and a half years ago, MIT entered into a research agreement with startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems to develop a next-generation fusion research experiment, called SPARC, as a precursor to a practical, emissions-free power plant. Philanthropy, it is popularly supposed, transfers money from the rich to the poor. This is not the case. In the US, which statistics show to be the most philanthropic of nations, barely a fifth of the money donated by big givers goes to the poor. A lot goes to the arts, sports teams and other cultural pursuits, and half goes to education and healthcare. At first glance that seems to fit the popular profile of “giving to good causes”. But dig down a little.

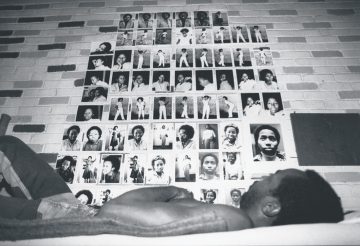

Philanthropy, it is popularly supposed, transfers money from the rich to the poor. This is not the case. In the US, which statistics show to be the most philanthropic of nations, barely a fifth of the money donated by big givers goes to the poor. A lot goes to the arts, sports teams and other cultural pursuits, and half goes to education and healthcare. At first glance that seems to fit the popular profile of “giving to good causes”. But dig down a little. WE CAN ALL AGREE NOW that American prisons are a malignant feature of contemporary life, broadening inequalities, destroying families, worsening racial disparities, and facilitating widespread state-sanctioned premature death, to name just a few of the most obvious iniquities. But inside these prisons, people do find imaginative ways to survive. The institutional culture of incarceration has spawned individual and communal acts of inspired genius—acts credited entirely to people, and not to the prisons where they are forced to live—modalities of making and ways of surviving that involve types of creativity unique to communities held captive. To do time in prison is to become an expert at doing time in prison, to develop specific skills and levels of knowledge that can only be acquired heuristically rather than gleaned, learned, read about. Experientially, prison alters sensory life: sight—drab and reduced colors and textures; sound—loud and invasive; human touch—not part of the ideological plan for “rehabilitation”; taste—very little aside from salt; smell—at least here in California, the smell of prisons up and down the state derives from a single overpowering cleaning solution used in every facility of the entire massive system and called, I kid you not, Cell Block 64.

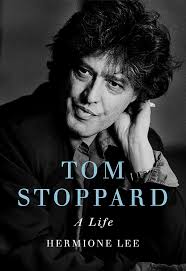

WE CAN ALL AGREE NOW that American prisons are a malignant feature of contemporary life, broadening inequalities, destroying families, worsening racial disparities, and facilitating widespread state-sanctioned premature death, to name just a few of the most obvious iniquities. But inside these prisons, people do find imaginative ways to survive. The institutional culture of incarceration has spawned individual and communal acts of inspired genius—acts credited entirely to people, and not to the prisons where they are forced to live—modalities of making and ways of surviving that involve types of creativity unique to communities held captive. To do time in prison is to become an expert at doing time in prison, to develop specific skills and levels of knowledge that can only be acquired heuristically rather than gleaned, learned, read about. Experientially, prison alters sensory life: sight—drab and reduced colors and textures; sound—loud and invasive; human touch—not part of the ideological plan for “rehabilitation”; taste—very little aside from salt; smell—at least here in California, the smell of prisons up and down the state derives from a single overpowering cleaning solution used in every facility of the entire massive system and called, I kid you not, Cell Block 64. Until I read Hermione Lee’s life of Tom Stoppard, I didn’t know it was possible to bask in envy. As if being handsome, funny and a dazzling writer (and good at cricket and fly-fishing) weren’t enough, Stoppard is immensely rich – not just in money but also, Lee shows, in family, lovers, friends and even, which may sound pompous, moral qualities. ‘What is the Good?’ Emily asks in his 2013 radio play Darkside. ‘It is nothing but a contest of kindness.’ We learn of his devotion to his mother, brother, sons and grandchildren, his ability to stay friends with his exes and his work on behalf of good causes, beneficiaries of which include the opposition in Belarus, which he has supported since before Lukashenko came to power, and refugees encamped at Calais. There are a couple of brilliant paragraphs late in the book about the meanings and pitfalls of charm, and also of luck. A small part of Stoppard’s good luck is that, unlike the subjects of most worthwhile biographies, he’s alive to enjoy this one.

Until I read Hermione Lee’s life of Tom Stoppard, I didn’t know it was possible to bask in envy. As if being handsome, funny and a dazzling writer (and good at cricket and fly-fishing) weren’t enough, Stoppard is immensely rich – not just in money but also, Lee shows, in family, lovers, friends and even, which may sound pompous, moral qualities. ‘What is the Good?’ Emily asks in his 2013 radio play Darkside. ‘It is nothing but a contest of kindness.’ We learn of his devotion to his mother, brother, sons and grandchildren, his ability to stay friends with his exes and his work on behalf of good causes, beneficiaries of which include the opposition in Belarus, which he has supported since before Lukashenko came to power, and refugees encamped at Calais. There are a couple of brilliant paragraphs late in the book about the meanings and pitfalls of charm, and also of luck. A small part of Stoppard’s good luck is that, unlike the subjects of most worthwhile biographies, he’s alive to enjoy this one. Pity the poor closed-caption writers. Pity the poor ASL interpreters. But most of all, pity poor us, the American electorate.

Pity the poor closed-caption writers. Pity the poor ASL interpreters. But most of all, pity poor us, the American electorate. Recorded history is five thousand years old. Modern science, which has been with us for just four centuries, has remade its trajectory. We are no smarter individually than our medieval ancestors, but we benefit, as a civilization, from antibiotics and electronics, vitamins and vaccines, synthetic materials and weather forecasts; we comprehend our place in the universe with an exactness that was once unimaginable. I’d found that science was two-faced: simultaneously thrilling and tedious, all-encompassing and narrow. And yet this was clearly an asset, not a flaw. Something about that combination had changed the world completely.

Recorded history is five thousand years old. Modern science, which has been with us for just four centuries, has remade its trajectory. We are no smarter individually than our medieval ancestors, but we benefit, as a civilization, from antibiotics and electronics, vitamins and vaccines, synthetic materials and weather forecasts; we comprehend our place in the universe with an exactness that was once unimaginable. I’d found that science was two-faced: simultaneously thrilling and tedious, all-encompassing and narrow. And yet this was clearly an asset, not a flaw. Something about that combination had changed the world completely. How can, and should, we talk to each other, especially to people with whom we disagree? “Free speech” is rightfully entrenched as an important value in liberal democratic societies, but implementing it consistently and fairly is a tricky business. Political theorist Teresa Bejan comes to this question from a philosophical and historical perspective, managing to relate broad principles to modern hot-button issues. We talk about the importance of tolerating disreputable beliefs, the senses in which speech acts can be harmful, and how “civility” places demands on listeners as well as speakers.

How can, and should, we talk to each other, especially to people with whom we disagree? “Free speech” is rightfully entrenched as an important value in liberal democratic societies, but implementing it consistently and fairly is a tricky business. Political theorist Teresa Bejan comes to this question from a philosophical and historical perspective, managing to relate broad principles to modern hot-button issues. We talk about the importance of tolerating disreputable beliefs, the senses in which speech acts can be harmful, and how “civility” places demands on listeners as well as speakers. Like many other liberals, I’m devastated by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, which opened the way for President Donald Trump to nominate a third Supreme Court justice in his first term. And I’m revolted by the hypocrisy of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s willingness to confirm Trump’s nominee after refusing to even allow a vote on Judge Merrick Garland.

Like many other liberals, I’m devastated by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, which opened the way for President Donald Trump to nominate a third Supreme Court justice in his first term. And I’m revolted by the hypocrisy of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s willingness to confirm Trump’s nominee after refusing to even allow a vote on Judge Merrick Garland.