Jamie McCallum in Aeon:

Jamie McCallum in Aeon:

Years ago, I set up a weekly Google Alert for the phrase ‘work ethic’ to help me gather material for the book I was writing. I have read thousands of these articles over the years. As individual stories, the alerts are only moderately interesting. A significant percentage of the pieces written in American newspapers and magazines that contain the phrase ‘work ethic’ are about sports, as star athletes are almost always routinely praised for their tireless practice-makes-perfect commitment. Others say the same about politicians, and a good portion are op-eds by elected officials or business leaders complaining about the pathetic state of the work ethic among today’s youth.

Taken as a whole, however, they illuminate a severe anxiety about a fundamental precept of the American civil religion. The work ethic is a tent-pole of national identity politics. Reading between the lines, across the media, or even just skimming the headlines, gives one the impression that we are a nation under attack. One national poll in 2015 found that 72 per cent of respondents said the United States ‘isn’t as great as it once was’. The principal culprit was the country’s declining belief in the value of hard work. More people thought ‘our own lagging work ethic’ was a larger threat to American greatness than the Islamic State, economic inequality, and competition with China.

Widespread anxiety about a diminished work ethic is confounding when considered against the actual data on how much time Americans spend working.

More here.

Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation:

Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation: Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic:

Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic: The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning

The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning  To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity.

To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity. I HAVE NEVER FELT WELCOME

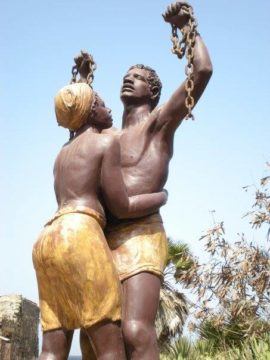

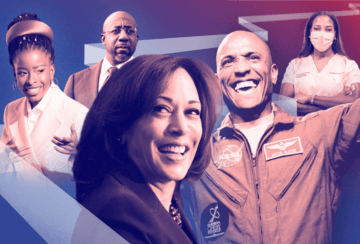

I HAVE NEVER FELT WELCOME  In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.

In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.

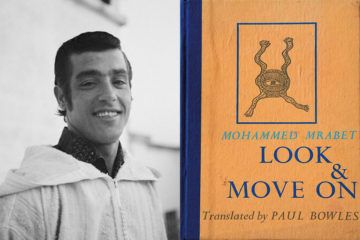

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet.

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet. When the New York Times Magazine ran

When the New York Times Magazine ran  In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was

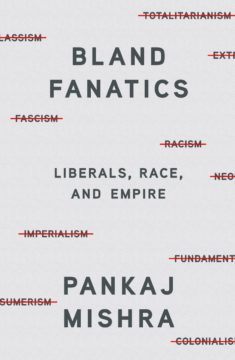

In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was  For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent

For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent  I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January.

I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January. Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And

Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And  It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.

It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.