Timothy Brennan in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

As an indictment of English and French scholarship on the Arab and Islamic worlds, Orientalism made its overall case clearly enough. The field of Oriental studies had managed to create a fantastical projection about Arabs and Islam that fit the biases of its Western audience. At times, these images were exuberant and intoxicating, at times infantilizing or hateful, but at no time did they describe Arabs and Muslims accurately. Over centuries, these images and attitudes formed a network of mutually reinforcing clichés mirrored in the policies of the media, the church, and the university. With the authority of seemingly objective science, new prejudices joined those already in circulation. This grand edifice of learning deprived Arabs of anything but a textual reality, usually based on a handful of medieval religious documents. As such, the Arab world was arrested within the classics of its own past. This much about Orientalism, it seems, was uncontroversial, although readers agreed on little else.

More here.

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy:

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy: Thomas Moynihan in Aeon:

Thomas Moynihan in Aeon: Alexander Zevin in New Left Review:

Alexander Zevin in New Left Review: Erica Eisen in Boston Review:

Erica Eisen in Boston Review: Aside from the flicker of fame that followed City of Quartz, Davis has managed to largely avoid the limelight for nearly four decades, despite receiving a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, a Lannan Literary Award, and many other honors along the way. For his devoted readers, part of his appeal is surely found in his writing style, which though forceful, self-assured, and playful, is also unapologetically precise, even scientific, making full use of a century-and-a-half’s worth of Marxist vocabulary. And part of it is his seemingly dour and idiosyncratic interests, which have led him to write books about the history of the car bomb, developmental patterns in contemporary slums, and the role of El Niño famines in nineteenth-century political economy.

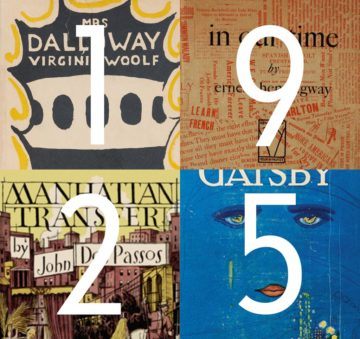

Aside from the flicker of fame that followed City of Quartz, Davis has managed to largely avoid the limelight for nearly four decades, despite receiving a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, a Lannan Literary Award, and many other honors along the way. For his devoted readers, part of his appeal is surely found in his writing style, which though forceful, self-assured, and playful, is also unapologetically precise, even scientific, making full use of a century-and-a-half’s worth of Marxist vocabulary. And part of it is his seemingly dour and idiosyncratic interests, which have led him to write books about the history of the car bomb, developmental patterns in contemporary slums, and the role of El Niño famines in nineteenth-century political economy. “An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking & ultimately nauseating.” So goes Virginia Woolf’s well-known complaint about “

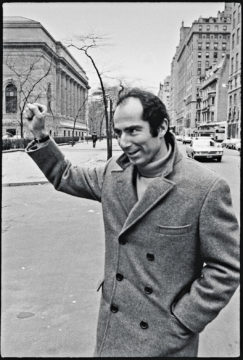

“An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking & ultimately nauseating.” So goes Virginia Woolf’s well-known complaint about “ When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.”

When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.” Among the many puzzles that confronted American sailors during World War II, few were as vexing as the sound of phantom enemies. Especially in the war’s early days, submarine crews and sonar operators listening for Axis vessels were often baffled by what they heard. When the USS Salmon surfaced to search for the ship whose rumbling propellers its crew had detected off the Philippines coast on Christmas Eve 1941, the submarine found only an empty expanse of moonlit ocean. Elsewhere in the Pacific, the USS Tarpon was mystified by a repetitive clanging and the USS Permit by what crew members described as the sound of “hammering on steel.” In the Chesapeake Bay, the clangor—likened by one sailor to “pneumatic drills tearing up a concrete sidewalk”—was so loud it threatened to detonate defensive mines and sink friendly ships.

Among the many puzzles that confronted American sailors during World War II, few were as vexing as the sound of phantom enemies. Especially in the war’s early days, submarine crews and sonar operators listening for Axis vessels were often baffled by what they heard. When the USS Salmon surfaced to search for the ship whose rumbling propellers its crew had detected off the Philippines coast on Christmas Eve 1941, the submarine found only an empty expanse of moonlit ocean. Elsewhere in the Pacific, the USS Tarpon was mystified by a repetitive clanging and the USS Permit by what crew members described as the sound of “hammering on steel.” In the Chesapeake Bay, the clangor—likened by one sailor to “pneumatic drills tearing up a concrete sidewalk”—was so loud it threatened to detonate defensive mines and sink friendly ships. A couple of weeks ago, I attended an interdisciplinary seminar featuring work in progress on law and humanities. After the guest presenter finished reading his chapter draft, the floor opened for discussion: Legal scholars pushed for more terminological precision, historians suggested alternative timelines, political scientists offered comparative context that called some of the author’s conclusions into question. It wasn’t until the frank, fun, productive conversation had wrapped up that I put my finger on what had been missing. Where was the praise?

A couple of weeks ago, I attended an interdisciplinary seminar featuring work in progress on law and humanities. After the guest presenter finished reading his chapter draft, the floor opened for discussion: Legal scholars pushed for more terminological precision, historians suggested alternative timelines, political scientists offered comparative context that called some of the author’s conclusions into question. It wasn’t until the frank, fun, productive conversation had wrapped up that I put my finger on what had been missing. Where was the praise? Alice and Bob, the stars of so many thought experiments, are cooking dinner when mishaps ensue. Alice accidentally drops a plate; the sound startles Bob, who burns himself on the stove and cries out. In another version of events, Bob burns himself and cries out, causing Alice to drop a plate.

Alice and Bob, the stars of so many thought experiments, are cooking dinner when mishaps ensue. Alice accidentally drops a plate; the sound startles Bob, who burns himself on the stove and cries out. In another version of events, Bob burns himself and cries out, causing Alice to drop a plate. And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs.

And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs. It’s 2050 and you’re due for your monthly physical exam. Times have changed, so you no longer have to endure an orifices check, a needle in your vein, and a week of waiting for your blood test results. Instead, the nurse welcomes you with, “The doctor will sniff you now,” and takes you into an airtight chamber wired up to a massive computer. As you rest, the volatile molecules you exhale or emit from your body and skin slowly drift into the complex artificial intelligence apparatus, colloquially known as Deep Nose. Behind the scene, Deep Nose’s massive electronic brain starts crunching through the molecules, comparing them to its enormous olfactory database. Once it’s got a noseful, the AI matches your odors to the medical conditions that cause them and generates a printout of your health. Your human doctor goes over the results with you and plans your treatment or adjusts your meds.

It’s 2050 and you’re due for your monthly physical exam. Times have changed, so you no longer have to endure an orifices check, a needle in your vein, and a week of waiting for your blood test results. Instead, the nurse welcomes you with, “The doctor will sniff you now,” and takes you into an airtight chamber wired up to a massive computer. As you rest, the volatile molecules you exhale or emit from your body and skin slowly drift into the complex artificial intelligence apparatus, colloquially known as Deep Nose. Behind the scene, Deep Nose’s massive electronic brain starts crunching through the molecules, comparing them to its enormous olfactory database. Once it’s got a noseful, the AI matches your odors to the medical conditions that cause them and generates a printout of your health. Your human doctor goes over the results with you and plans your treatment or adjusts your meds. On February 22nd, in an office in White Plains, two lawyers handed over a hard drive to a Manhattan Assistant District Attorney, who, along with two investigators, had driven up from New York City in a heavy snowstorm. Although the exchange didn’t look momentous, it set in motion the next phase of one of the most significant legal showdowns in American history. Hours earlier, the Supreme Court had ordered

On February 22nd, in an office in White Plains, two lawyers handed over a hard drive to a Manhattan Assistant District Attorney, who, along with two investigators, had driven up from New York City in a heavy snowstorm. Although the exchange didn’t look momentous, it set in motion the next phase of one of the most significant legal showdowns in American history. Hours earlier, the Supreme Court had ordered  “I

“I