Empty Souls

…… Tibetan prayer flags

…… flap in the wind

…… no one to talk to

Why Tower Air? I ask as my husband packs a suitcase to get ready to attend his

mother’s funeral. Because it’s a bargain, he says.

Wouldn’t you rather fly a major carrier?

I pull a card from my Tarot deck. Out of the 78 possibilities, it’s the Tower that shows

up. Flames shoot from the top of a crumbling brick tower while a couple with shock

imprinted on their faces falls through the air, crowns flying. There’s no soft landing

in sight.

I plead with my husband to book with another airline, but he says he’ll be fine. I

shouldn’t put such faith in divination. As I entertain a couple of acquaintances, the

phone rings. My husband’s voice sounds far away.

…… dusk signals the jasmine to release its scent

I’m at Kennedy. We had to make an emergency landing. While flames shot from the

engine, the pilot told us to put our heads in our laps and brace for impact. The silence

was so thick, no one could make a sound. I took my wallet from my jacket, placed it in

the seat pocket facing me, just in case my body couldn’t be identified. And then I saw

a newspaper headline which seemed so vivid and real—son dies in plane crash after

attending mother’s funeral. It was the most bizarre experience. I thought my life was

over, that I’d never see you again. When we got off the plane, some people actually

kissed the ground. Everyone is shaken including the pilot’s wife. It was her husband’s

last flight before retirement.

While my guests stuff themselves on tacos and guacamole, I try to regain composure.

Don’t sweat the small stuff, they tell me. Get over it. Move on. Come eat. I want to

throw them both out but instead I bite my tongue until it aches. I count the minutes

until they’re out of my space.

…… the cat brings home a screech owl

I sense disappointment in my brother-in-law’s voice. Had there been a fatal accident,

he’d inherit all of the mother’s estate. I so need to vent, but my next-door neighbor,

who caught a blip about it on the news, is nonchalant.

During break in qi gong class, my husband tries to tell a classmate about the incident,

but the instructor glares at him as if to say, keep your sad stories to yourself.

…… The taste

…… of loneliness

…… evening meal

by Alexis Rotella

from Rattle #70, Winter 2020

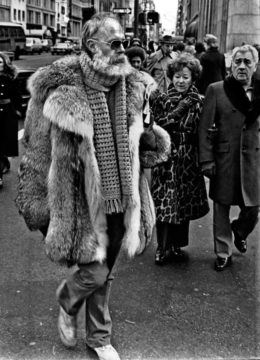

Gorey favored huge fur coats paired with jeans, sweaters, sneakers, and ever-present small gold hoops in each ear. His constantly-donned coats earned him a 1978 write-up in the New York Times titled “Portrait of the Artist as a Furry Creature.” (Gorey eventually auctioned off his coat collection and donated the money to PETA.)

Gorey favored huge fur coats paired with jeans, sweaters, sneakers, and ever-present small gold hoops in each ear. His constantly-donned coats earned him a 1978 write-up in the New York Times titled “Portrait of the Artist as a Furry Creature.” (Gorey eventually auctioned off his coat collection and donated the money to PETA.)

One of the most vacuous idioms we use about our moral and social debates is the idea of being “on the side of history”. The plain meaning of this is that “history” – the record of human actions – has an inevitable trajectory, and we had better get on board with it or suffer the consequences.

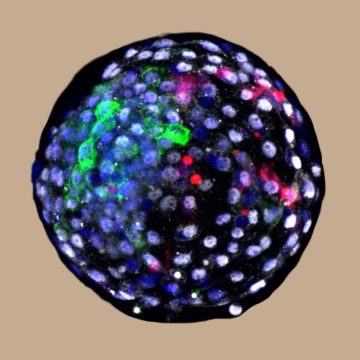

One of the most vacuous idioms we use about our moral and social debates is the idea of being “on the side of history”. The plain meaning of this is that “history” – the record of human actions – has an inevitable trajectory, and we had better get on board with it or suffer the consequences. Scientists have successfully grown monkey embryos containing human cells for the first time — the latest milestone in a rapidly advancing field that has drawn ethical questions.

Scientists have successfully grown monkey embryos containing human cells for the first time — the latest milestone in a rapidly advancing field that has drawn ethical questions. I

I Long before the advent of non-fungible tokens, some advocates of digital art argued that there is no meaningful distinction between a “virtual” object and a “physical” one. Such a division, they believed, partakes of the fallacy of “digital dualism,” the imprecise belief that a file is somehow less “real” than a painting on canvas, when in fact both are products of mind and time accreted to the permanence of matter. Less arty or newfangled is the old law of property. A contract is a ghost story for adults: It turns vaporous whatevers—labor time, carbon, pixel—into a coin struck by the handshake of exchange and the creep of law. Ownership was always a song and a dance and a fusillade.

Long before the advent of non-fungible tokens, some advocates of digital art argued that there is no meaningful distinction between a “virtual” object and a “physical” one. Such a division, they believed, partakes of the fallacy of “digital dualism,” the imprecise belief that a file is somehow less “real” than a painting on canvas, when in fact both are products of mind and time accreted to the permanence of matter. Less arty or newfangled is the old law of property. A contract is a ghost story for adults: It turns vaporous whatevers—labor time, carbon, pixel—into a coin struck by the handshake of exchange and the creep of law. Ownership was always a song and a dance and a fusillade. A team of Egyptian archaeologists

A team of Egyptian archaeologists  Think of the American Civil Liberties Union during the last two decades of the 20th century, and a certain type of person invariably comes to mind: shrewd, thick-skinned, and possessed of an unwavering—some might say irritating—commitment to principle. The men and women of the ACLU were liberals in the most honorable, but increasingly obsolescent, meaning of the term. They understood that the measure of democracy lies in the impartial application of its laws, and were prepared to defend anyone whose constitutional rights were trampled upon, irrespective of their political views or the repercussions that mounting such a defense might entail.

Think of the American Civil Liberties Union during the last two decades of the 20th century, and a certain type of person invariably comes to mind: shrewd, thick-skinned, and possessed of an unwavering—some might say irritating—commitment to principle. The men and women of the ACLU were liberals in the most honorable, but increasingly obsolescent, meaning of the term. They understood that the measure of democracy lies in the impartial application of its laws, and were prepared to defend anyone whose constitutional rights were trampled upon, irrespective of their political views or the repercussions that mounting such a defense might entail. In September 2017, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, the storm first made landfall on a small island off the main island’s eastern coast called Cayo Santiago. At the time, the fate of Cayo Santiago and its inhabitants was barely a footnote in the dramatic story of Maria, which became Puerto Rico’s worst natural disaster, killing 3,000 people and disrupting normal life for months.

In September 2017, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, the storm first made landfall on a small island off the main island’s eastern coast called Cayo Santiago. At the time, the fate of Cayo Santiago and its inhabitants was barely a footnote in the dramatic story of Maria, which became Puerto Rico’s worst natural disaster, killing 3,000 people and disrupting normal life for months. JERUSALEM — The annual Israel Prize ceremony is supposed to be an august and unifying event, a beloved highlight of the Independence Day celebrations that fall on Thursday this year. This being Israel, it is rarely without controversy. The latest ruckus goes to the heart of the political divides and culture wars rocking the country’s liberal democratic foundations even as it remains lodged in a two-year

JERUSALEM — The annual Israel Prize ceremony is supposed to be an august and unifying event, a beloved highlight of the Independence Day celebrations that fall on Thursday this year. This being Israel, it is rarely without controversy. The latest ruckus goes to the heart of the political divides and culture wars rocking the country’s liberal democratic foundations even as it remains lodged in a two-year  It’s hard if not impossible to imagine a figure of Weil’s stature in the intellectual and political culture of today’s left, the only region of the political spectrum where she might possibly fit. And not just because of her religiosity, which would of course instantly ghettoize her. It’s also because she’s so hard to pin down with any neat, easy label—or rather, because the labels are too many and apparently conflicting. (She’d be eaten alive on Twitter from all sides—or, worse, simply shunned and ignored.) “An anarchist who espoused conservative ideals,” Zaretsky writes in his opening pages, “a pacifist who fought in the Spanish Civil War, a saint who refused baptism, a mystic who was a labor militant, a French Jew who was buried in the Catholic section of an English cemetery, a teacher who dismissed the importance of solving a problem, the most willful of individuals who advocated the extinction of the self: here are but a few of the paradoxes Weil embodied.”

It’s hard if not impossible to imagine a figure of Weil’s stature in the intellectual and political culture of today’s left, the only region of the political spectrum where she might possibly fit. And not just because of her religiosity, which would of course instantly ghettoize her. It’s also because she’s so hard to pin down with any neat, easy label—or rather, because the labels are too many and apparently conflicting. (She’d be eaten alive on Twitter from all sides—or, worse, simply shunned and ignored.) “An anarchist who espoused conservative ideals,” Zaretsky writes in his opening pages, “a pacifist who fought in the Spanish Civil War, a saint who refused baptism, a mystic who was a labor militant, a French Jew who was buried in the Catholic section of an English cemetery, a teacher who dismissed the importance of solving a problem, the most willful of individuals who advocated the extinction of the self: here are but a few of the paradoxes Weil embodied.” Beyond erasing this diversity, casting Palestinian radicalism as innately Islamic severs resistance from the essential question of land and geography. The novel reflects this: Nahr’s status as the daughter of Palestinian refugees in Kuwait certainly affects her life—she is pushed out of an official dance troupe, and her family’s allegiance is suspected after Saddam Hussein’s invasion. But being Palestinian doesn’t take hold as a political reality until she lives in her ancestral homeland. What fuels her fight isn’t a divine commandment about good and evil; it is the land itself. Nahr observes settlers encroaching on a Palestinian village, and wonders how Bilal and his mother have been able to keep them away from their land. She visits her mother’s childhood home, in Haifa, and picks figs from a tree her grandfather planted, before being chased off by a Jewish woman who now lives there. She helps to redirect water from a pipe meant for settlers to the olive groves. There is violence inflicted upon this land, but Abulhawa centers its beauty: “I was content to just sit there in the splendid silence of the hills, where the quiet amplified small sounds—the wind rustling trees; sheep chewing, roaming, bleating, breathing; the soft crackle of the fire; the purr of Bilal’s breathing,” Nahr reflects. “I realized how much I had come to love these hills; how profound was my link to this soil.”

Beyond erasing this diversity, casting Palestinian radicalism as innately Islamic severs resistance from the essential question of land and geography. The novel reflects this: Nahr’s status as the daughter of Palestinian refugees in Kuwait certainly affects her life—she is pushed out of an official dance troupe, and her family’s allegiance is suspected after Saddam Hussein’s invasion. But being Palestinian doesn’t take hold as a political reality until she lives in her ancestral homeland. What fuels her fight isn’t a divine commandment about good and evil; it is the land itself. Nahr observes settlers encroaching on a Palestinian village, and wonders how Bilal and his mother have been able to keep them away from their land. She visits her mother’s childhood home, in Haifa, and picks figs from a tree her grandfather planted, before being chased off by a Jewish woman who now lives there. She helps to redirect water from a pipe meant for settlers to the olive groves. There is violence inflicted upon this land, but Abulhawa centers its beauty: “I was content to just sit there in the splendid silence of the hills, where the quiet amplified small sounds—the wind rustling trees; sheep chewing, roaming, bleating, breathing; the soft crackle of the fire; the purr of Bilal’s breathing,” Nahr reflects. “I realized how much I had come to love these hills; how profound was my link to this soil.”

A year ago, there was no snow on the ground, and I was thinking about icebergs. “We’d rather have the iceberg than the ship,” begins the first stanza of Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Imaginary Iceberg,” and continues,

A year ago, there was no snow on the ground, and I was thinking about icebergs. “We’d rather have the iceberg than the ship,” begins the first stanza of Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Imaginary Iceberg,” and continues,