Melissa Mohr in The Christian Science Monitor:

In February, the rover Perseverance arrived on Mars after an almost eight-month journey, tasked with looking for signs of ancient life. Though no firm evidence of life beyond Earth has yet been found, the English language is already full of words to talk about it. The search for life on other planets is part of the science of astrobiology. The prefix astro- is “star” in Latin and Greek and, predictably, appears in astronomy, the study of objects beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

In February, the rover Perseverance arrived on Mars after an almost eight-month journey, tasked with looking for signs of ancient life. Though no firm evidence of life beyond Earth has yet been found, the English language is already full of words to talk about it. The search for life on other planets is part of the science of astrobiology. The prefix astro- is “star” in Latin and Greek and, predictably, appears in astronomy, the study of objects beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

Astrobiologists aren’t just looking for microbes on Mars. They are also trying to predict what life might look like under conditions vastly different from those on Earth. Physicists Luis Anchordoqui and Eugene Chudnovsky speculate that there might be life inside stars, for example. Hypothetical particles called magnetic monopoles might assemble into chains and 3D structures, and be able to replicate by using energy from the star’s fusion. This is not “life as we know it,” to misquote “Star Trek,” but these particle chains would be “alive” at least by some definitions. A group of astrobiologists has proposed a term that would more obviously include “creatures” like these, so unlike anything found on Earth: lyfe. Lyfe (pronounced “loife”) is a broader category that would encourage scientists to think outside the box, to “open [them]selves up to exploring the full parameter space of physical and chemical interactions that may create life,” write Stuart Bartlett and Michael Wong.

More here.

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans. What Reich wanted to understand was the body itself: why you might want to escape or subdue it, why it remains a naked source of power. His wild life draws together aspects of bodily experience that remain intensely relevant now, from illness to sex, anti-fascist direct action to incarceration. The writer and civil rights activist

What Reich wanted to understand was the body itself: why you might want to escape or subdue it, why it remains a naked source of power. His wild life draws together aspects of bodily experience that remain intensely relevant now, from illness to sex, anti-fascist direct action to incarceration. The writer and civil rights activist  The curtain rises on a dim, drab room. An alarm sounds, and a woman wakes. She tries to rouse her sleeping child and husband, calling out: “Get up!”

The curtain rises on a dim, drab room. An alarm sounds, and a woman wakes. She tries to rouse her sleeping child and husband, calling out: “Get up!”

Adam Tooze in the LRB:

Adam Tooze in the LRB: Robert Kuttner in the New York Review of Books:

Robert Kuttner in the New York Review of Books: Carlos Sardina Galache in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Carlos Sardina Galache in the NLR’s Sidecar: Dániel Oláh in Evonomics:

Dániel Oláh in Evonomics: Growing up, I never saw my Korean-American parents touch each other. No hugs or kisses, or even pats on the back. It wasn’t the byproduct of a loveless marriage, just the consequences of a life centered on survival — that endless list of unsexy chores. I’ve lived 30 years without acknowledging such biographical details, accepting that the nuances of my life could never make it into mainstream culture.

Growing up, I never saw my Korean-American parents touch each other. No hugs or kisses, or even pats on the back. It wasn’t the byproduct of a loveless marriage, just the consequences of a life centered on survival — that endless list of unsexy chores. I’ve lived 30 years without acknowledging such biographical details, accepting that the nuances of my life could never make it into mainstream culture. When we talk, we naturally gesture—we open our palms, we point, we chop the air for emphasis. Such movement may be more than superfluous hand flapping. It helps communicate ideas to listeners and even appears to help speakers think and learn. A growing field of psychological research is exploring the potential of having students or teachers gesture as pupils learn. Studies have shown that people remember material better when they make spontaneous gestures, watch a teacher’s movements or use their hands and arms to imitate the instructor. More recent work suggests that telling learners to move in specific ways can help them learn—even when they are unaware of why they are making the motions.

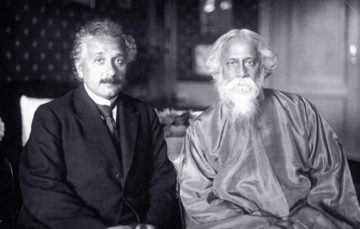

When we talk, we naturally gesture—we open our palms, we point, we chop the air for emphasis. Such movement may be more than superfluous hand flapping. It helps communicate ideas to listeners and even appears to help speakers think and learn. A growing field of psychological research is exploring the potential of having students or teachers gesture as pupils learn. Studies have shown that people remember material better when they make spontaneous gestures, watch a teacher’s movements or use their hands and arms to imitate the instructor. More recent work suggests that telling learners to move in specific ways can help them learn—even when they are unaware of why they are making the motions. Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at the age of eighty, is a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. Anyone who becomes familiar with this large and flourishing tradition will be impressed by the power of Tagore’s presence in Bangladesh and in India. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh.

Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at the age of eighty, is a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. Anyone who becomes familiar with this large and flourishing tradition will be impressed by the power of Tagore’s presence in Bangladesh and in India. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh. During every waking moment, we humans and other animals have to balance on the edge of our awareness of past and present. We must absorb new sensory information about the world around us while holding on to short-term memories of earlier observations or events. Our ability to make sense of our surroundings, to learn, to act and to think all depend on constant, nimble interactions between perception and memory.

During every waking moment, we humans and other animals have to balance on the edge of our awareness of past and present. We must absorb new sensory information about the world around us while holding on to short-term memories of earlier observations or events. Our ability to make sense of our surroundings, to learn, to act and to think all depend on constant, nimble interactions between perception and memory. The British spy agency GCHQ is so aggressive, extreme and unconstrained by law or ethics that the NSA — not exactly world renowned for its restraint — often farms out spying activities too scandalous or illegal for the NSA to their eager British counterparts. There is, as the Snowden

The British spy agency GCHQ is so aggressive, extreme and unconstrained by law or ethics that the NSA — not exactly world renowned for its restraint — often farms out spying activities too scandalous or illegal for the NSA to their eager British counterparts. There is, as the Snowden