Andrew Blum in Lapham’s Quarterly:

The first extrasomatic energy source was fire, mastered by prehistoric societies 250,000 years ago. Pack animals provided ancient humans with an order of magnitude more energy. But not until waterwheels came into common use in the medieval era was there any common inanimate source to master. The Canadian historian Vaclav Smil notes that the Domesday Book records 5,624 water mills in southern and eastern England in the late eleventh century, one for every 350 people. Yet it would take another eight hundred years, into the Industrial Revolution, for their performance to be increased by another order of magnitude. Then things sped up. By the 1880s, the electrical system as we know it was recognizable, and crude oil began its rise to dominance for transportation. Ox by ox, waterwheel by waterwheel, engine by engine, the peak capacity of individual generating units rose approximately fifteen million times in ten thousand years, with more than 99 percent of that rise occurring during the twentieth century. Of those leaps, the most dramatic was nuclear fission, the breaking apart of atoms. Fission weapons shaped the century’s geopolitics; fission power plants still supply 10 percent of the world’s electricity.

Except now fission has run its course. In the wake of the Fukushima disaster, society’s appetite for nuclear risk has diminished. The costs of engineering even greater safety make fission power less economically viable compared to the falling costs of renewable sources like wind and solar. Averting further climate catastrophe requires broad policy changes—and some key new technologies. A step-change improvement in energy storage would open up new ways of using renewable energy, like solar energy at night and wind energy on calm days. More efficient ways of removing carbon from the atmosphere, at scale, might help change the climate again.

But the greatest potential for innovation—the closest thing to a technological silver bullet—remains fusion. Fusion is what powers the sun: a self-sustaining reaction in which isotopes of hydrogen at tens of millions of degrees fuse to form helium, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process. Fusion carries none of fission’s catastrophic risks. Its raw materials are abundant and safe, derived primarily from seawater. Its waste is minimally radioactive—more like what’s produced by hospitals than fission power plants. And there is no risk of meltdowns: when a fusion reactor’s power is shut off, its reaction stops.

More here.

“In North America we pose a far greater risk to our bats than they do to us,” said O’Keefe, a bat ecologist and professor of environmental science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, an illness that jumped from animal hosts to humans. But disease transfer isn’t just a one-way street. It takes only a bit of evolutionary bad luck to turn a bat’s head cold into a human’s killer. But it takes only a little more for the same virus to jump from humans to other animals. Zoonosis begets reverse zoonosis, which can, in turn, come back around to zoonosis again. A virus we give to a bat could, someday, come back around to reinfect us. Animals’ health is ours, ours is theirs, theirs is ours.

“In North America we pose a far greater risk to our bats than they do to us,” said O’Keefe, a bat ecologist and professor of environmental science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease, an illness that jumped from animal hosts to humans. But disease transfer isn’t just a one-way street. It takes only a bit of evolutionary bad luck to turn a bat’s head cold into a human’s killer. But it takes only a little more for the same virus to jump from humans to other animals. Zoonosis begets reverse zoonosis, which can, in turn, come back around to zoonosis again. A virus we give to a bat could, someday, come back around to reinfect us. Animals’ health is ours, ours is theirs, theirs is ours. Polidori: Well, America is a Protestant country. Protestants don’t take so well to pathos, so they think that I’m a reactionary, because I am making misery look beautiful. And so because of this, I am minimizing the plight of the victims. I only get this in Anglo-Saxon countries, the rest of the world doesn’t think that way.

Polidori: Well, America is a Protestant country. Protestants don’t take so well to pathos, so they think that I’m a reactionary, because I am making misery look beautiful. And so because of this, I am minimizing the plight of the victims. I only get this in Anglo-Saxon countries, the rest of the world doesn’t think that way. On the stage of an empty concert hall, the Austrian-born composer

On the stage of an empty concert hall, the Austrian-born composer  I often think about George Berkeley’s observation (without recalling quite where he offered it) that when we think we are imagining to ourselves the heat of the sun, what we are really imagining is the heat of a stove or a similar familiar source of mundane household warmth. A stove is already hot enough to reduce my hand to ash fairly quickly. And without a hand left, without any nerve endings to give me any report at all on the external world, I’m hardly in a position to note the difference between 300 degrees Fahrenheit and 5,700 degrees Kelvin. Both, Berkeley thinks, are just too darn hot.

I often think about George Berkeley’s observation (without recalling quite where he offered it) that when we think we are imagining to ourselves the heat of the sun, what we are really imagining is the heat of a stove or a similar familiar source of mundane household warmth. A stove is already hot enough to reduce my hand to ash fairly quickly. And without a hand left, without any nerve endings to give me any report at all on the external world, I’m hardly in a position to note the difference between 300 degrees Fahrenheit and 5,700 degrees Kelvin. Both, Berkeley thinks, are just too darn hot. The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities.

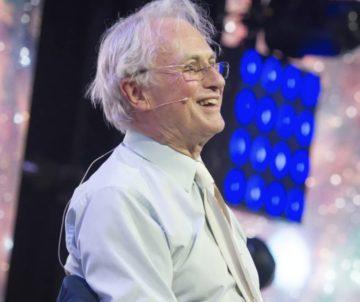

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community.

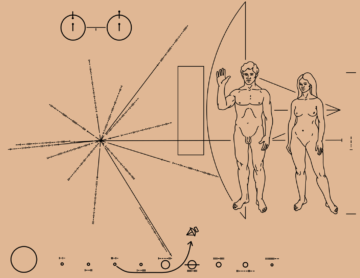

Last week, the American Humanist Association (AHA) stripped British author Richard Dawkins of his 1996 Humanist of the Year award after he made a comment on Twitter that offended some in the transgender community. How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans. Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing.

Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing. Disney’s 2019 remake of its 1994 classic “The Lion King” was a box-office success, grossing more than one and a half billion dollars. But it was also, in some ways, a failed experiment. The film’s photo-realistic, computer-generated animals spoke with the rich, complex voices of actors such as Donald Glover and Chiwetel Ejiofor—and many viewers found it hard to reconcile the complex intonations of those voices with the feline gazes on the screen. In giving such persuasively nonhuman animals human personalities and thoughts, the film created a kind of cognitive dissonance. It had been easier to imagine the interiority of the stylized beasts in the original film. Disney’s filmmakers had stumbled onto an issue that has long fascinated philosophers and zoologists: the gap between animal minds and our own. The dream of bridging that divide, perhaps by speaking with and understanding animals, goes back to antiquity. Solomon was said to have possessed a ring that gave him the power to converse with beasts—a legend that furnished the title of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz’s pioneering book on animal psychology, “

Disney’s 2019 remake of its 1994 classic “The Lion King” was a box-office success, grossing more than one and a half billion dollars. But it was also, in some ways, a failed experiment. The film’s photo-realistic, computer-generated animals spoke with the rich, complex voices of actors such as Donald Glover and Chiwetel Ejiofor—and many viewers found it hard to reconcile the complex intonations of those voices with the feline gazes on the screen. In giving such persuasively nonhuman animals human personalities and thoughts, the film created a kind of cognitive dissonance. It had been easier to imagine the interiority of the stylized beasts in the original film. Disney’s filmmakers had stumbled onto an issue that has long fascinated philosophers and zoologists: the gap between animal minds and our own. The dream of bridging that divide, perhaps by speaking with and understanding animals, goes back to antiquity. Solomon was said to have possessed a ring that gave him the power to converse with beasts—a legend that furnished the title of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz’s pioneering book on animal psychology, “ It might seem surprising that origami, the ancient Japanese art of paper folding, is an integral part of engineering. However, origami structures can be folded up compactly and deployed at the nano- and macroscales seemingly without effort. They are therefore well suited for a wide range of applications, including robotics

It might seem surprising that origami, the ancient Japanese art of paper folding, is an integral part of engineering. However, origami structures can be folded up compactly and deployed at the nano- and macroscales seemingly without effort. They are therefore well suited for a wide range of applications, including robotics

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant.

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it

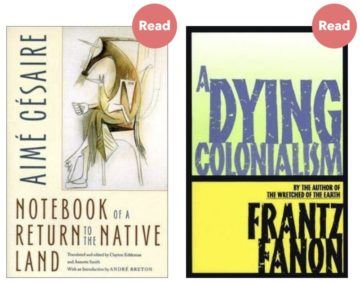

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it  Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic.

Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic.