Michael Gordin in LA Review of Books:

TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent Pew Research Center data back this up a bit, but there’s plenty of leeriness about Science among Democrats as well.

TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent Pew Research Center data back this up a bit, but there’s plenty of leeriness about Science among Democrats as well.

And it gets messier when you actually drill down into specifics. The masks are an exemplary case. Saying that Science supports mask-wearing is unquestionably true, whether you define that support as a consensus among epidemiologists or as the conclusion reached by meta-studies of the scientific literature. Now consider some other questions: Should we open schools when most of the country is not vaccinated? Is it okay to put this nuclear waste depository in the next county? Let’s ask Science! Turns out this Science entity doesn’t have a single voice, and in many cases hearing what it has to say isn’t straightforward. As intellectual historian Andrew Jewett notes at the end of Science under Fire, “Such blanket injunctions to place our trust in science, or religion, or the humanities, or any other broad framework, offer remarkably little guidance on how to respond to the social possibilities raised by particular scientific or technical innovations.”

Nonetheless, the exhortations continue. This implies that there are quite a few people out there who are anti-Science, or at least cautious about placing unbounded faith in it. Those who are anti-“anti-Science” often portray such individuals as tinfoil-hat-wearing conspiracy theorists, while the anti-Science people see their detractors as credulous lemmings exposing themselves to myriad physical and spiritual harms.

Enter Jewett, who is anti-anti-anti-Science.

More here.

Nearly every day while writing my new book,

Nearly every day while writing my new book,  There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators.

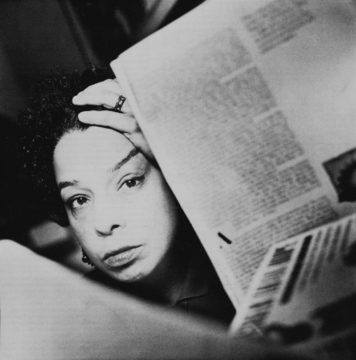

There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators. Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.

Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.

Coming on the heels of

Coming on the heels of  James Carville: You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like

James Carville: You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he  As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong.

As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong. Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The

Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The  At the core of Anton Chekov’s short story, ‘

At the core of Anton Chekov’s short story, ‘ Released from the silo of conventional philosophy, I found the neuroscientists at the medical school to be uniformly hospitable and curious about what I was up to. A human brain was indeed delivered to me in the anatomy lab, and holding it my hands, I felt an almost reverential humility toward this tissue that had embodied someone’s love and knowledge and skills. It looked so small, relative to what a human brain can do.

Released from the silo of conventional philosophy, I found the neuroscientists at the medical school to be uniformly hospitable and curious about what I was up to. A human brain was indeed delivered to me in the anatomy lab, and holding it my hands, I felt an almost reverential humility toward this tissue that had embodied someone’s love and knowledge and skills. It looked so small, relative to what a human brain can do. In cities big and small, hospitals are too full to accept new patients and diagnostic centers take up to three days or more to do chest scans of those who might have Covid-19. Doctors and hospital staff are completely exhausted.

In cities big and small, hospitals are too full to accept new patients and diagnostic centers take up to three days or more to do chest scans of those who might have Covid-19. Doctors and hospital staff are completely exhausted.