Nidhi Subbaraman in Nature:

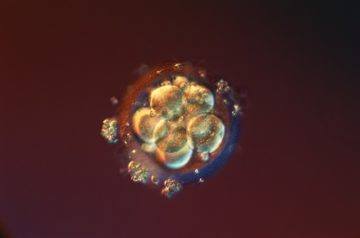

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The ISSCR made this change and others to its guidelines for biomedical research in response to rapid advances in the field, including the ability to create embryo-like structures from human stem cells. In addition to relaxing the ‘14-day rule’, for instance, the group advises against editing genes in human embryos until the safety of genome editing is better established.

More here.

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick. A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s.

A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s. I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think.

I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think. One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace.

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace. I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song.

I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song. Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician

Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician  When we first traveled to

When we first traveled to  Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members.

Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members. The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures.

The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures. Reading Battles in the Desert, one will note the special magic of Pacheco’s writing — that simplicity, so deceptive and so masterful. The narrative voice is a well-calibrated device gliding through the reality of things, stories, and emotions, always giving the impression that memory never betrays. “Pacheco’s craft and mastery make writing look easy,” writes Luis Jorge Boone in “José Emilio Pacheco: Un lector fuera del tiempo” (“José Emilio Pacheco: a reader outside of time”), an essay on the author’s work. “Achieving that almost magical ease took Pacheco years of rewrites, edits, cuts. The layers upon layers of work the author put into his books over the years is legendary.”

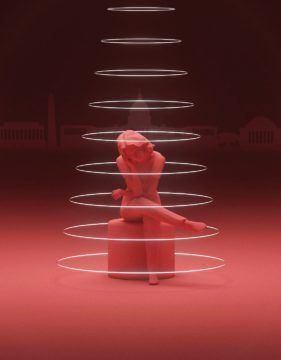

Reading Battles in the Desert, one will note the special magic of Pacheco’s writing — that simplicity, so deceptive and so masterful. The narrative voice is a well-calibrated device gliding through the reality of things, stories, and emotions, always giving the impression that memory never betrays. “Pacheco’s craft and mastery make writing look easy,” writes Luis Jorge Boone in “José Emilio Pacheco: Un lector fuera del tiempo” (“José Emilio Pacheco: a reader outside of time”), an essay on the author’s work. “Achieving that almost magical ease took Pacheco years of rewrites, edits, cuts. The layers upon layers of work the author put into his books over the years is legendary.” During the final weeks of the Trump Administration, a senior official on the National Security Council sat at his desk in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, across from the West Wing, on the White House grounds. It was mid-November, and he had recently returned from a work trip abroad. At the end of the day, he left the building and headed toward his car, which was parked a few hundred yards away, along the Ellipse, between the White House and the Washington Monument. As he walked, he began to hear a ringing in his ears. His body went numb, and he had trouble controlling the movement of his legs and his fingers. Trying to speak to a passerby, he had difficulty forming words. “It came on very suddenly,” the official recalled later, while describing the experience to a colleague. “In a matter of about seven minutes, I went from feeling completely fine to thinking, Oh, something’s not right, to being very, very worried and actually thinking I was going to die.”

During the final weeks of the Trump Administration, a senior official on the National Security Council sat at his desk in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, across from the West Wing, on the White House grounds. It was mid-November, and he had recently returned from a work trip abroad. At the end of the day, he left the building and headed toward his car, which was parked a few hundred yards away, along the Ellipse, between the White House and the Washington Monument. As he walked, he began to hear a ringing in his ears. His body went numb, and he had trouble controlling the movement of his legs and his fingers. Trying to speak to a passerby, he had difficulty forming words. “It came on very suddenly,” the official recalled later, while describing the experience to a colleague. “In a matter of about seven minutes, I went from feeling completely fine to thinking, Oh, something’s not right, to being very, very worried and actually thinking I was going to die.”