Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Artificial Intimacy: The Next Giant Social Experiment on Children

Kristina Lerman and David Chu at After Babel:

Researchers have only just begun to systematically explore the psychological dynamics of human-AI relationships. Recent studies suggest that AI chatbots have high emotional competence. For example, responses from social chatbots have been rated as more compassionate than those of licensed physicians [Ayers et al, 2023.] and expert crisis counselors [Ovsyannikova et al., 2025], although knowing the response came from the chatbot rather than a human can reduce perceived empathy [Rubin et al., 2025]. Still, chatbots provide genuine emotional support. One study found that lonely college students credited their chatbot companions with preventing suicidal thoughts [Maples et al., 2024]. However, most of these studies have focused on (young) adults. We still know very little about how children and adolescents respond to emotionally intelligent AI — or how such interactions may shape their development, relationships, or self-concept over time.

Researchers have only just begun to systematically explore the psychological dynamics of human-AI relationships. Recent studies suggest that AI chatbots have high emotional competence. For example, responses from social chatbots have been rated as more compassionate than those of licensed physicians [Ayers et al, 2023.] and expert crisis counselors [Ovsyannikova et al., 2025], although knowing the response came from the chatbot rather than a human can reduce perceived empathy [Rubin et al., 2025]. Still, chatbots provide genuine emotional support. One study found that lonely college students credited their chatbot companions with preventing suicidal thoughts [Maples et al., 2024]. However, most of these studies have focused on (young) adults. We still know very little about how children and adolescents respond to emotionally intelligent AI — or how such interactions may shape their development, relationships, or self-concept over time.

To better understand this phenomenon, we turned to Reddit, a popular online platform where people gather in forums to talk about everything from hobbies and relationships to mental health. In recent years, forums dedicated to AI companions have grown rapidly.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Musician Bringing the Bagpipes Into the Avant-Garde

Elena Saavedra Buckley at the New Yorker:

One night this past spring, the audience members at a bagpipe concert in Red Hook, Brooklyn, could be organized into two neat categories: people who knew little to nothing about bagpipes—the majority—and people who knew so much that the backs of their jackets were festooned with regimental patches for the uniformed pipe bands of various Northeastern cities. The latter group had mostly come to the event together in a van from Connecticut, where they lived. One of the jacket-wearers, a man with a septum piercing named Benjamin, spends his free time 3-D-printing custom bagpipe drones—the cylindrical pipes that sound the instrument’s continuous, harmonically dense vibrations. When I asked him why he did this, he seemed stunned by the question. “Um, more drone?” he said.

Everyone had come to see the twenty-seven-year-old Brìghde (pronounced “Breech-huh”) Chaimbeul, considered one of the most skillful and interesting bagpipe players in the world, who was visiting from her native Scotland. Chaimbeul walked onstage in a witchy outfit, grounded by a navy tartan skirt, her raven hair up in a half bun and her dark-browed face set calmly. Shahzad Ismaily, a celebrated experimental-jazz musician, sat next to her with a chunky Moog synthesizer on his lap.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brìghde Chaimbeul Playing Bagpipes

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

An Israeli Daughter Confronts Her Father’s Role in the Tantura massacre from 1948

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Meanings Of Mein Kampf

Richard J Evans at the New Statesman:

Just over 100 years ago, on 18 July 1925, the most notorious book of the 20th century was published – Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”) by Adolf Hitler, who became dictator of Germany less than eight years later. It has been described as the epitome of “absolute evil”, the “most disgusting of all books” and “the nadir of depravity”. More than a few historians have regarded the book as providing a blueprint for what came later, from the destruction of German democracy and the genocide of Europe’s Jews to the launching of the Second World War and the ruthless ethnic cleansing of Eastern Europe by the Nazis. Its centenary provides an opportunity for re-examining its origins, its nature and its influence.

Just over 100 years ago, on 18 July 1925, the most notorious book of the 20th century was published – Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”) by Adolf Hitler, who became dictator of Germany less than eight years later. It has been described as the epitome of “absolute evil”, the “most disgusting of all books” and “the nadir of depravity”. More than a few historians have regarded the book as providing a blueprint for what came later, from the destruction of German democracy and the genocide of Europe’s Jews to the launching of the Second World War and the ruthless ethnic cleansing of Eastern Europe by the Nazis. Its centenary provides an opportunity for re-examining its origins, its nature and its influence.

Hitler began writing the book during a period of enforced idleness following his arrest and imprisonment for leading a violent attempt to overthrow the state government of Bavaria on 9 November 1923 – the so-called Beer Hall Putsch – which ended in a hail of bullets fired at him and his Nazi supporters by the Bavarian police. Brought to trial in Munich on 26 February 1924, Hitler claimed that he had acted purely out of patriotic motives.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

why everyone is so unhappy with the system, and what may come next

James Surowiecki in The Yale Review:

This is a pivotal moment for American capitalism. Even though GDP and household incomes have grown steadily in this century, most Americans say they feel dissatisfied with the state of the economy and believe that the country’s economic future will be worse than its past. There is a deep sense of discontent with capitalism, and a conviction that the two paradigms of political economy that have dominated the West since World War II—Keynesian social democracy on the one hand and free-market-centered neoliberalism on the other—no longer work. And while politicians like Bernie Sanders, with his left-wing populism, and Donald Trump, with his right-wing nationalism, have tapped into this discontent, what the new order will ultimately look like remains wholly unclear.

This is a pivotal moment for American capitalism. Even though GDP and household incomes have grown steadily in this century, most Americans say they feel dissatisfied with the state of the economy and believe that the country’s economic future will be worse than its past. There is a deep sense of discontent with capitalism, and a conviction that the two paradigms of political economy that have dominated the West since World War II—Keynesian social democracy on the one hand and free-market-centered neoliberalism on the other—no longer work. And while politicians like Bernie Sanders, with his left-wing populism, and Donald Trump, with his right-wing nationalism, have tapped into this discontent, what the new order will ultimately look like remains wholly unclear.

This is, then, a perfect moment for John Cassidy’s new book, Capitalism and Its Critics, which takes, as its title suggests, a wide-ranging look at the history of capitalism through the eyes of some of its foremost critics. Cassidy includes not just the obvious ones—Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Thorstein Veblen, and Thomas Piketty, for instance—but also lesser-known yet extraordinarily interesting writers, such as the Irish proto-socialist William Thompson, the French Peruvian feminist socialist Flora Tristan, and the Indian economist J. C. Kumarappa.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Poem

and greenhouse and topsoil and basil greens

and cowshit and snowfall and spinach knife

and woodsmoke and watering can and common thistle

and potato digger and peach trees

and poison parsnip and romaine hearts

and rockpiles and spring trilliums and ramp circles

what song of grassblade

what creak of dark rustle tree

and blueblack wind from the north

this vetch this grapevine

this waterhose this mosspatch

sunflower gardens in the lowland

dog graves between the apple trees

this fistfull of onion tops

this garlic laid silent in the barn

this green this green this green

sweet cucumber leaf

sweet yellow bean

and all this I try to make a human shape

the darkness regenerating a shadow of a limb

my tongue embraces the snap pea

and so it is sweet

how does the rusted golfcart in the chickweed

inform my daily breath

I’m sorry I want to say

to the unhearing spaces

between the dogwood trees

for my tiny little life

I have pressed into

your bruising green skin

by Lucy Walker

from Pank Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, August 20, 2025

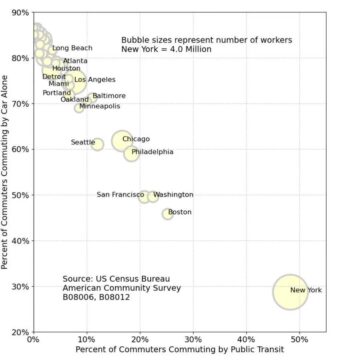

America has only one real city

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Americans who go to Tokyo or Paris or Seoul or London are often wowed by the efficient train systems, dense housing, and walkable city streets lined with shops and restaurants. And yet in these countries, many secondary cities also have these attractive features. Go to Nagoya or Fukuoka, and the trains will be almost as convenient, the houses almost as dense, and the streets almost as attractive as in Tokyo.

Americans who go to Tokyo or Paris or Seoul or London are often wowed by the efficient train systems, dense housing, and walkable city streets lined with shops and restaurants. And yet in these countries, many secondary cities also have these attractive features. Go to Nagoya or Fukuoka, and the trains will be almost as convenient, the houses almost as dense, and the streets almost as attractive as in Tokyo.

The U.S. is very different. We have New York City, and that’s about it. People from Chicago or Boston may protest that their own cities are also walkable, but transit use statistics show just how big the gap is between NYC and everybody else…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Best Popular Science Books of 2025: The Royal Society Book Prize

Cal Flyn interviews Sandra Knapp at Five Books:

You chaired the judging panel for the 2025 Royal Society Book Prize. What were you and your fellow judges looking for when you selected the best new popular science books?

You chaired the judging panel for the 2025 Royal Society Book Prize. What were you and your fellow judges looking for when you selected the best new popular science books?

There are so many good science books that it was really, really difficult. We were looking for books with interesting, solid, well-researched science, but which were also incredibly readable. You want a book that a reader will come away from having learned something new about science, but also that they had a good time reading that book. So it’s about learning and pleasure being mixed into one, and the product being something that you perhaps want to read again.

It does seem that there are different flavours of intelligence. One being what it takes to make a brilliant scientist, and another being able to communicate clearly those complex ideas.

Yes. Not all of the books on our shortlist are actually written by scientists; some are by science writers or journalists. But whichever side of that spectrum you sit on, you need to be able to put yourself in another person’s shoes to be able to tell a story in a compelling way.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Interpretability: Understanding how AI models think

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

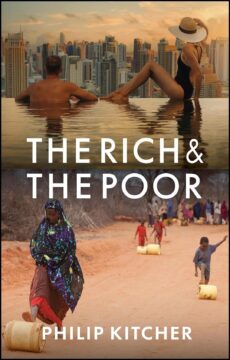

The Case for Pragmatic Progress

Michela Massimi in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

The hard statistics underlying poverty and social mobility opportunities for children and other marginalized individuals might seem like an unlikely entry point for a philosophy book. Yet they are the impetus for philosopher of science Philip Kitcher’s latest project: The Rich and the Poor (2025). The book’s cover sets the tone. Featuring side-by-side portraits of rich individuals enjoying cocktails by an infinity pool and a woman with children kicking home canisters filled with water collected at a nearby water aid station, it is meant to be—and is—uncanny.

The hard statistics underlying poverty and social mobility opportunities for children and other marginalized individuals might seem like an unlikely entry point for a philosophy book. Yet they are the impetus for philosopher of science Philip Kitcher’s latest project: The Rich and the Poor (2025). The book’s cover sets the tone. Featuring side-by-side portraits of rich individuals enjoying cocktails by an infinity pool and a woman with children kicking home canisters filled with water collected at a nearby water aid station, it is meant to be—and is—uncanny.

Kitcher is not new to book projects that engage with ethical problems and wider policy questions. From Science, Truth, and Democracy (2001) to The Ethical Project (2011), from The Seasons Alter: How to Save Our Planet in Six Acts (co-authored with Evelyn Fox Keller, 2017) to Moral Progress (2021), he has pioneered a method of philosophy and thinking about science that is both sensitive to socioeconomic realities and responsive to ethical challenges. The Rich and the Poor continues this intellectual trajectory while also bringing in autobiographical details: Kitcher himself benefited from an improbable combination of “progressive politicians, a sensitive boy king, and an unusually thoughtful and kind schoolmaster.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Aldous Huxley on the Ultimate Revolution (1962)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Miłosz’s Engagement with History

Peter Dale Scott at Church Life Journal:

This poem reads like a precursor to the decision to act (like Einstein) in the second “fragment” of “To Albert Einstein.” The poet, as if in a New Year’s resolution, has now decided that it is better to speak out dangerously than to be silent. But he has not yet settled on what he will say (i.e., make a clean break with the post-war Polish state for which he was still working).

This poem reads like a precursor to the decision to act (like Einstein) in the second “fragment” of “To Albert Einstein.” The poet, as if in a New Year’s resolution, has now decided that it is better to speak out dangerously than to be silent. But he has not yet settled on what he will say (i.e., make a clean break with the post-war Polish state for which he was still working).

It could even be that by writing the first “fragment” Milosz contemplated his enforced muteness, and recognized that he must correct it. His silence was a feature above all of his status as a diplomat. But this was precisely when his U.S. post was ending; and he was obsessed with the decision whether or not to defect and start a new life. But to defect would prolong indefinitely his separation from his Polish-speaking audience behind the Iron Curtain, a second and deeper reason why any cries from him could not be heard.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mexican Philosophy for the 21st Century

Juan Carlos González at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Carlos Sánchez has dedicated a lot of thought and ink to two questions: (1) Is there such a thing as “Mexican philosophy”? and (2) If there is such a thing, does it matter? Throughout his career, Sánchez has consistently answered the first question affirmatively. In response to the second, Sánchez has shared that this tradition matters to him for personal reasons. Mexican philosophy has enriched his life, providing resources not only for deep philosophical speculation but also for coming to grips with his identity as a Mexican American. Yet, with respect to the question of why this tradition should matter to everyone regardless of their background, he at one point confessed, “There is, of course, a well-developed and highly nuanced answer to the question as to why one should study Mexican philosophy ‘at all’. But I haven’t found it yet” (2019).

Carlos Sánchez has dedicated a lot of thought and ink to two questions: (1) Is there such a thing as “Mexican philosophy”? and (2) If there is such a thing, does it matter? Throughout his career, Sánchez has consistently answered the first question affirmatively. In response to the second, Sánchez has shared that this tradition matters to him for personal reasons. Mexican philosophy has enriched his life, providing resources not only for deep philosophical speculation but also for coming to grips with his identity as a Mexican American. Yet, with respect to the question of why this tradition should matter to everyone regardless of their background, he at one point confessed, “There is, of course, a well-developed and highly nuanced answer to the question as to why one should study Mexican philosophy ‘at all’. But I haven’t found it yet” (2019).

Mexican Philosophy for the 21st Century delivers a well-developed, highly nuanced, and compelling answer to the question of why one should study Mexican philosophy “at all.” Sánchez’s central task is to “normalize” Mexican philosophy outside Mexico, or to demonstrate to the broader world of academic philosophy (especially in the United States) that Mexican philosophy has an original, rich, and overlooked set of tools for addressing human crises.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Tao of Duck

I sit on a high rock over a lake watching

a duck swim. Sun warm, rock cold, not yet summer.

Friends about, but not near, lake maybe half

a mile wide, duck a third of the way across,

making steady progress. I wait for it to grow

bored with paddling, to unfurl its wings, kick

its feet free, and erupt into air. My mind’s eye

sees beneath the surface one wide webby foot

pushing back while the other, momentarily

narrow, pulls forward – again and again, legs

alternating, chug chugging like a two stroke engine.

I grow annoyed, If you want to get to the other

side, fly, my reasonable self thinks at the bird,

but it sails on, little feathered boat on a large sea,

a stubborn captain in the bridge above the bill,

eye on the far shore, calling into the speaker tube,

Full Foot Ahead. He will not push the fly button.

Strange and aggravating, this duck’s way,

as aggravating as a saint’s.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Pleasure of Patterns in Art

Samuel Keyser in The MIT Press Reader:

Made at the high point of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” was a poke in the eye of abstract expressionism. Not only was it blatantly mimetic, but it was being blatantly mimetic with a mundane commercial product found in every supermarket and corner grocery store in America. When people think of repetition in painting, they probably think first of these iconic soup cans.

Made at the high point of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” was a poke in the eye of abstract expressionism. Not only was it blatantly mimetic, but it was being blatantly mimetic with a mundane commercial product found in every supermarket and corner grocery store in America. When people think of repetition in painting, they probably think first of these iconic soup cans.

But not all repetition is as in-your-face or as disruptive as “Campbell’s Soup Cans.” One painting from the Impressionist period is particularly pertinent. I am thinking of “Paris Street; Rainy Day” by Gustave Caillebotte. Currently housed in the Art Institute of Chicago, it was originally exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in 1877. It is probably Caillebotte’s best-known work. I consider it a masterpiece and regret that I have never seen the real thing. Even so, it never ceases to bowl me over. Discussions of it typically focus on the incredible verisimilitude of the painting, the sense that it is photographic in its vivid capture of an ordinary moment.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brain-Computer Interface Lets Users Communicate Using Thoughts

Sahana Sitaraman in The Scientist:

There’s a voice inside most people’s minds that comes alive when they listen, read, or prepare to speak. This “internal monologue” is thought to support complex cognitive processes like working memory, logical reasoning, and motivation.1 In fact, inner speech continues to thrive in many individuals who are unable to speak owing to injury or disease.2 More than half a century ago, Jacques Vidal, a computer scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, proposed the idea for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs); systems that could use electrical signals in the brain to control prosthetic devices.3

There’s a voice inside most people’s minds that comes alive when they listen, read, or prepare to speak. This “internal monologue” is thought to support complex cognitive processes like working memory, logical reasoning, and motivation.1 In fact, inner speech continues to thrive in many individuals who are unable to speak owing to injury or disease.2 More than half a century ago, Jacques Vidal, a computer scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, proposed the idea for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs); systems that could use electrical signals in the brain to control prosthetic devices.3

Since then, scientists have designed and developed BCIs that have enabled people with quadriplegia to control a computer cursor, a robotic arm, and even move their own limb. Recently, a person with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—a neurodegenerative disease—who had severe difficulties speaking, was able to carry out a freeform conversation with the help of a speech BCI.4 The neuroprosthesis accurately translated brain activity into coherent sentences while the person tried to speak to the best of their ability. However, the reliance on attempted speech can fatigue the user and limit communication speed.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, August 19, 2025

K-pop culture inspires innocence, joy and belonging

A. Stefanie Ruiz, Femida Handy, and Sunwoo Park in The Conversation:

“Born with voices that could drive back the darkness,” the character Celine, a former K-pop idol, narrates at the start of Netflix’s new release “KPop Demon Hunters.” “Our music ignites the soul and brings people together.”

“Born with voices that could drive back the darkness,” the character Celine, a former K-pop idol, narrates at the start of Netflix’s new release “KPop Demon Hunters.” “Our music ignites the soul and brings people together.”

The breakout success of “KPop Demon Hunters,” Netflix’s most-watched original animated film, highlights how “hallyu,” or the Korean Wave, keeps expanding its pop cultural reach. The movie, which follows a fictional K-pop girl group whose members moonlight as demon slayers, amassed over 26 million views globally in a single week and topped streaming charts in at least 33 countries.

From K-pop and K-dramas to beauty products and e-sports, hallyu – which refers to the global popularity of South Korean culture – has drawn in millions of fans worldwide. But beyond entertainment, many young people describe how their engagement with Korean culture supports their mental health and sense of belonging.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Future of Climate Change Is on Mauritius

Ariel Saramandi at The Dial:

My husband and I married in September 2018. We planned our wedding a year in advance. We didn’t even think about the sea, its surges, its rhythms. It was a feat of stupidity, for two people who grew up on an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean.

My husband and I married in September 2018. We planned our wedding a year in advance. We didn’t even think about the sea, its surges, its rhythms. It was a feat of stupidity, for two people who grew up on an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean.

Two days after our wedding we watched the butter-hued moon rise above the water. A hiss as the waves drew back from the coast then thrashed against the shore, gaining ground by the minute. If we’d chosen to get married 48 hours later we wouldn’t have had a venue.

We were married on a stretch of basalt rock leading out to sea, an elevated slice of shore covered in sand, garnered with thatched huts, wooden tables and a structure that served as our secular altar. Now they were all soused in brine. We walked along a stretch of coast owned by a hotel group, examining the damage. The sea stripped the plump beach of sand, laying bare the fat canvas bags underneath; the waves exposed the roots of coconut trees, gnarled, purple-black like gum disease.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.