Elizabeth Bruenig in The Atlantic:

By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those selfsame chiders would doubtlessly decry, under different circumstances, as cancel culture or censorship—it no longer mattered what, exactly, Omar had said. They had already managed to make a news cycle out of it: mission accomplished. Now, following Democratic outrage and Republican calls for a floor vote to strip Omar of her committee assignments, let me record the following for posterity: Omar demonstrably did not say what she’s been accused of having said; what she did say was true; and every politico using this opportunity to take a swing at her likely knows those two things—they just think you don’t.

By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those selfsame chiders would doubtlessly decry, under different circumstances, as cancel culture or censorship—it no longer mattered what, exactly, Omar had said. They had already managed to make a news cycle out of it: mission accomplished. Now, following Democratic outrage and Republican calls for a floor vote to strip Omar of her committee assignments, let me record the following for posterity: Omar demonstrably did not say what she’s been accused of having said; what she did say was true; and every politico using this opportunity to take a swing at her likely knows those two things—they just think you don’t.

What did Omar say? Context is key. In 2020, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on International Criminal Court prosecutors who moved to investigate potential U.S. war crimes in Afghanistan as well as potential Israeli crimes in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, arguing that because the U.S. and Israel aren’t members of the ICC, the court has no right to adjudicate such matters. (The ICC recognizes the State of Palestine as a party to its governing statute, a decision that the U.S. insists the ICC lacks the power to make.) Omar vocally opposed the sanctions—as did the European Union, the president of the ICC’s Assembly of States Parties, Senator Patrick Leahy, and, presumably, anyone skeptical of America’s willingness to look into its own savagery abroad.

During a June 7 budget hearing, Omar asked Secretary of State Antony Blinken a series of questions based on the ICC incident. First, Omar praised Blinken for lifting the Trump-era sanctions. Then she pointed out that he nevertheless still opposed an ICC investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan and Palestine—including, in the first case, offenses allegedly perpetrated by the U.S., the Afghan national government, and the Taliban; and, in the second, Israeli security forces and Hamas. Omar asked, “Where do we think victims are supposed to go for justice? And what justice mechanisms do you support?”

To which Blinken replied, more or less, that the U.S. and Israel are competent to adjudicate all of the above. This raised the obvious question Then why haven’t they?, but Omar’s time was up, and she politely yielded to the next representative. Later that day, Omar’s official Twitter account shared a video and tweeted a paraphrase of the exchange. The tweet read, in its entirety: “We must have the same level of accountability and justice for all victims of crimes against humanity. We have seen unthinkable atrocities committed by the U.S., Hamas, Israel, Afghanistan, and the Taliban. I asked @SecBlinken where people are supposed to go for justice.”

More here.

The strength and value of the ordinary man is a through line in James’s diverse body of work, and nowhere is this interest more evident than in Minty Alley, which eschews the world stage in favor of a single yard in a back alley in Port of Spain. In this book, Haynes, a young, passive middle-class intellectual, is forced after his mother’s death to rent lodgings in a working-class neighborhood, the kind of place where men kept mistresses and things that were improper to discuss occurred, according to the James documentary Every Cook Can Govern. Here, Haynes’s life is vastly, if temporarily, enriched by the people he meets and the relationships he develops. James himself was not from such a neighborhood, but while conducting research for the book, he interviewed local women about their lives. The results are, as Evaristo writes in her introduction, “a story about a Caribbean community in relationship with itself” and “a peek into a society of nearly one hundred years ago, which shows us that while the circumstances are different, our essential passions, preoccupations and ambitions remain the same.”

The strength and value of the ordinary man is a through line in James’s diverse body of work, and nowhere is this interest more evident than in Minty Alley, which eschews the world stage in favor of a single yard in a back alley in Port of Spain. In this book, Haynes, a young, passive middle-class intellectual, is forced after his mother’s death to rent lodgings in a working-class neighborhood, the kind of place where men kept mistresses and things that were improper to discuss occurred, according to the James documentary Every Cook Can Govern. Here, Haynes’s life is vastly, if temporarily, enriched by the people he meets and the relationships he develops. James himself was not from such a neighborhood, but while conducting research for the book, he interviewed local women about their lives. The results are, as Evaristo writes in her introduction, “a story about a Caribbean community in relationship with itself” and “a peek into a society of nearly one hundred years ago, which shows us that while the circumstances are different, our essential passions, preoccupations and ambitions remain the same.”

Assassination signifies the taking of life. So, obviously, does murder. They are not, however, synonymous. Assassination is planned. It most probably involves an ambush or trap, and before that high-level debates and decisions made in meetings, which typically are not minuted. Murder doesn’t generally involve such things. Assassinations are intended. They are tactical instruments and tools – if not also proxies – of war. They are, equally, evasions of war and bulwarks against tyranny. Michael Burleigh is dubious about the beneficial effects of governmentally sanctioned killing. However, a perhaps unforeseen outcome of his relentlessly sanguinary book is the implication that the planet, far from being sullied by opérations ponctuelles, might be a happier place were a few more tyrants to be treated to well-aimed headshots. There can, for instance, be no doubt that had Benito Mussolini been shot and strung up in Piazzale Loreto a few years earlier than he was, he would not have bought a road map to catastrophe from Adolf Hitler.

Assassination signifies the taking of life. So, obviously, does murder. They are not, however, synonymous. Assassination is planned. It most probably involves an ambush or trap, and before that high-level debates and decisions made in meetings, which typically are not minuted. Murder doesn’t generally involve such things. Assassinations are intended. They are tactical instruments and tools – if not also proxies – of war. They are, equally, evasions of war and bulwarks against tyranny. Michael Burleigh is dubious about the beneficial effects of governmentally sanctioned killing. However, a perhaps unforeseen outcome of his relentlessly sanguinary book is the implication that the planet, far from being sullied by opérations ponctuelles, might be a happier place were a few more tyrants to be treated to well-aimed headshots. There can, for instance, be no doubt that had Benito Mussolini been shot and strung up in Piazzale Loreto a few years earlier than he was, he would not have bought a road map to catastrophe from Adolf Hitler. WHEN PEOPLE TALK ABOUT TRUTH OR DARE, the notorious 1991 documentary about Madonna’s Blond Ambition tour, they tend to mention the same handful of scenes. The gay kiss. Madonna deep-throating a bottle of Vichy Catalan (not Evian, as often misremembered). Kevin Costner calling the show “neat” and Madonna making a puking gesture. Are these the best scenes in the film? No, but they passed for scandal in 1991 and so they made an impression. In retrospect they feel a little try-hard, a little overhyped, but that’s because we’re watching from the world Madonna made. With the distance of thirty years, it’s easier to appreciate everything else. Her intense relationship with her dancers. The range of personality on display. Above all there’s the serendipity of timing and access. Few pop stars of Madonna’s magnitude would give a filmmaker the free hand she gave director Alek Keshishian in 1991, including the Madonna of 2021. Few documentarians would have as much as he did to show for it.

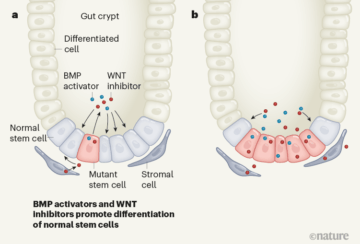

WHEN PEOPLE TALK ABOUT TRUTH OR DARE, the notorious 1991 documentary about Madonna’s Blond Ambition tour, they tend to mention the same handful of scenes. The gay kiss. Madonna deep-throating a bottle of Vichy Catalan (not Evian, as often misremembered). Kevin Costner calling the show “neat” and Madonna making a puking gesture. Are these the best scenes in the film? No, but they passed for scandal in 1991 and so they made an impression. In retrospect they feel a little try-hard, a little overhyped, but that’s because we’re watching from the world Madonna made. With the distance of thirty years, it’s easier to appreciate everything else. Her intense relationship with her dancers. The range of personality on display. Above all there’s the serendipity of timing and access. Few pop stars of Madonna’s magnitude would give a filmmaker the free hand she gave director Alek Keshishian in 1991, including the Madonna of 2021. Few documentarians would have as much as he did to show for it. Decades of research have revealed how mutations contribute to the evolution of malignant cells and to the ultimate characteristics of a given tumour. There is growing recognition that the surrounding tissue environment affects the natural selection of these mutation-driven characteristics. Less appreciated, however, have been the effects of interactions between malignant cells and their neighbouring wild-type cells — and how, through these interactions, malignant cells shape the surrounding environment to their advantage. Writing in Nature,

Decades of research have revealed how mutations contribute to the evolution of malignant cells and to the ultimate characteristics of a given tumour. There is growing recognition that the surrounding tissue environment affects the natural selection of these mutation-driven characteristics. Less appreciated, however, have been the effects of interactions between malignant cells and their neighbouring wild-type cells — and how, through these interactions, malignant cells shape the surrounding environment to their advantage. Writing in Nature,  Mishra was moved to republish these essays in their hardcover coffin, he remarks in his introduction, as a response to Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these essays were written before Brexit, the election of Trump, or the advent of COVID-19. They lack the degree of prophetic force that Mishra might think appropriate. The title itself reprises a phrase due to Reinhold Niebuhr: “[A]mong the lesser culprits of history,” Niebuhr wrote in 1959, “are the bland fanatics of western civilization who regard the highly contingent achievements of our culture as the final form and norm of human existence.”

Mishra was moved to republish these essays in their hardcover coffin, he remarks in his introduction, as a response to Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these essays were written before Brexit, the election of Trump, or the advent of COVID-19. They lack the degree of prophetic force that Mishra might think appropriate. The title itself reprises a phrase due to Reinhold Niebuhr: “[A]mong the lesser culprits of history,” Niebuhr wrote in 1959, “are the bland fanatics of western civilization who regard the highly contingent achievements of our culture as the final form and norm of human existence.” Any system in which politicians represent geographical districts with boundaries chosen by the politicians themselves is vulnerable to gerrymandering: carving up districts to increase the amount of seats that a given party is expected to win. But even fairly-drawn boundaries can end up quite complex, so how do we know that a given map is unfairly skewed? Math comes to the rescue. We can ask whether the likely outcome of a given map is very unusual within the set of all possible reasonable maps. That’s a hard math problem, however — the set of all possible maps is pretty big — so we have to be clever to solve it. I talk with geometer Jordan Ellenberg about how ideas like random walks and Markov chains help us judge the fairness of political boundaries.

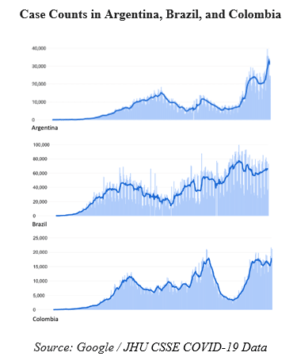

Any system in which politicians represent geographical districts with boundaries chosen by the politicians themselves is vulnerable to gerrymandering: carving up districts to increase the amount of seats that a given party is expected to win. But even fairly-drawn boundaries can end up quite complex, so how do we know that a given map is unfairly skewed? Math comes to the rescue. We can ask whether the likely outcome of a given map is very unusual within the set of all possible reasonable maps. That’s a hard math problem, however — the set of all possible maps is pretty big — so we have to be clever to solve it. I talk with geometer Jordan Ellenberg about how ideas like random walks and Markov chains help us judge the fairness of political boundaries. At the start of the year, there was reason to hope that we were beginning to see the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the daily rate of new cases from the holiday surge began to drop precipitously, and the vaccine rollout accelerated soon thereafter. Although Europe lagged in the early months of 2021, there, too, the tide started to turn by April, as the pace of vaccination finally picked up.

At the start of the year, there was reason to hope that we were beginning to see the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the daily rate of new cases from the holiday surge began to drop precipitously, and the vaccine rollout accelerated soon thereafter. Although Europe lagged in the early months of 2021, there, too, the tide started to turn by April, as the pace of vaccination finally picked up. But what does it mean when a building comes into existence as architecture only by accident—through contingency—under the erotic and transgressive conditions of an observer who was not supposed to be there seeing what was never supposed to be seen? There’s no usable lesson about “design” here, or urbanism, that the developer and his paid draughtsfolk might take away. No change to public policy or city codes. The experience of what we might think of as “the architectural,” in this instance, runs counter to every single intention behind the creation of this generic reflecting structure. It’s an experience born of incompleteness, of transience, like the spring itself.

But what does it mean when a building comes into existence as architecture only by accident—through contingency—under the erotic and transgressive conditions of an observer who was not supposed to be there seeing what was never supposed to be seen? There’s no usable lesson about “design” here, or urbanism, that the developer and his paid draughtsfolk might take away. No change to public policy or city codes. The experience of what we might think of as “the architectural,” in this instance, runs counter to every single intention behind the creation of this generic reflecting structure. It’s an experience born of incompleteness, of transience, like the spring itself. Neel was, to use a much-abused word, a humanist—and not only because she was a figurative painter. Unlike ponderously performative portraitists like Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, Neel did not objectify her subjects. She looked at them, and very often, they stared back at her. You might call her portraits a frank exchange of views. The gray-eyed woman who is the subject of “Elenka” (1936) could perform laser surgery with the intensity of her gaze. The expression on the face of Neel’s dying mother, bundled in a flannel robe, shrinking back and propped in a chair for “Last Sickness” (1953), is a lacerating blend of fear, reproach and shame. One of the two kids portrayed in “The Black Boys” (1967) is resigned, whereas the other, staring straight at the viewer, makes a challenge of his boredom.

Neel was, to use a much-abused word, a humanist—and not only because she was a figurative painter. Unlike ponderously performative portraitists like Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, Neel did not objectify her subjects. She looked at them, and very often, they stared back at her. You might call her portraits a frank exchange of views. The gray-eyed woman who is the subject of “Elenka” (1936) could perform laser surgery with the intensity of her gaze. The expression on the face of Neel’s dying mother, bundled in a flannel robe, shrinking back and propped in a chair for “Last Sickness” (1953), is a lacerating blend of fear, reproach and shame. One of the two kids portrayed in “The Black Boys” (1967) is resigned, whereas the other, staring straight at the viewer, makes a challenge of his boredom. By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those

By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those  E

E “Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more.

“Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more. Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial

Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial