Carl Zimmer in The New York Times (2011):

Vladimir Nabokov may be known to most people as the author of classic novels like “Lolita” and “Pale Fire.” But even as he was writing those books, Nabokov had a parallel existence as a self-taught expert on butterflies. He was the curator of lepidoptera at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and he collected the insects across the United States. He published detailed descriptions of hundreds of species. And in a speculative moment in 1945, he came up with a sweeping hypothesis for the evolution of the butterflies he studied, a group known as the Polyommatus blues. He envisioned them coming to the New World from Asia over millions of years in a series of waves.

Vladimir Nabokov may be known to most people as the author of classic novels like “Lolita” and “Pale Fire.” But even as he was writing those books, Nabokov had a parallel existence as a self-taught expert on butterflies. He was the curator of lepidoptera at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and he collected the insects across the United States. He published detailed descriptions of hundreds of species. And in a speculative moment in 1945, he came up with a sweeping hypothesis for the evolution of the butterflies he studied, a group known as the Polyommatus blues. He envisioned them coming to the New World from Asia over millions of years in a series of waves.

Few professional lepidopterists took these ideas seriously during Nabokov’s lifetime. But in the years since his death in 1977, his scientific reputation has grown. And over the past 10 years, a team of scientists has been applying gene-sequencing technology to his hypothesis about how Polyommatus blues evolved. Last week in The Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, they reported that Nabokov was absolutely right.

“It’s really quite a marvel,” said Naomi Pierce of Harvard, a co-author of the paper.

Nabokov inherited his passion for butterflies from his parents. When his father was imprisoned by the Russian authorities for his political activities, the 8-year-old Vladimir brought a butterfly to his cell as a gift. As a teenager, Nabokov went on butterfly-hunting expeditions and carefully described the specimens he caught, imitating the scientific journals he read in his spare time. Had it not been for the Russian Revolution, which forced his family into exile in 1919, Nabokov said that he might have become a full-time lepidopterist.

In his European exile, Nabokov visited butterfly collections in museums. He used the proceeds of his second novel, “King, Queen, Knave,” to finance an expedition to the Pyrenees, where he and his wife, Vera, netted more than a hundred species. The rise of the Nazis drove Nabokov into exile once more in 1940, this time to the United States. It was there that Nabokov found his greatest fame as a novelist. It was also there that he delved deepest into the science of butterflies.

Nabokov spent much of the 1940s dissecting a confusing group of species called Polyommatus blues. He developed forward-thinking ways to classifying the butterflies, based on differences in their genitalia. He argued that what were thought to be closely related species were actually only distantly related.

More here.

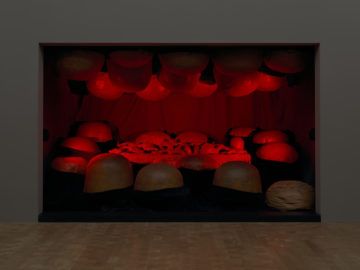

I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural.

I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural.

Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these.

Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these. The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics. Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead.

Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead. It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty.

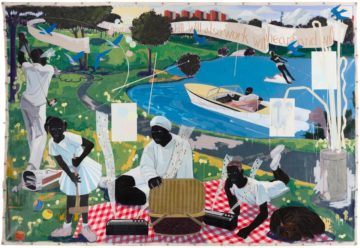

It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty. For the first thirty years of his career, Kerry James Marshall was a successful but little known artist. His figurative paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and videos appeared in gallery and museum shows here and abroad, and selling them was never a problem. He won awards, residencies, and grants, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1997, but in the contemporary-art world, which started to look more closely at Black artists in the nineties, Marshall was an outlier, and happy to be one. He had an unshakable confidence in himself as an artist, and the undistracted solitude of his practice allowed him to spend most of his time in the studio. The curator Helen Molesworth told me that during the three years it took to put together “Mastry,” Marshall’s first major retrospective in the United States, which opened in 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “there were still people in the art world who didn’t know who he was.”

For the first thirty years of his career, Kerry James Marshall was a successful but little known artist. His figurative paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and videos appeared in gallery and museum shows here and abroad, and selling them was never a problem. He won awards, residencies, and grants, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1997, but in the contemporary-art world, which started to look more closely at Black artists in the nineties, Marshall was an outlier, and happy to be one. He had an unshakable confidence in himself as an artist, and the undistracted solitude of his practice allowed him to spend most of his time in the studio. The curator Helen Molesworth told me that during the three years it took to put together “Mastry,” Marshall’s first major retrospective in the United States, which opened in 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “there were still people in the art world who didn’t know who he was.” J

J Ever since 1796, when English scientist and physician Edward Jenner successfully inoculated an eight-year-old boy with cowpox to protect him from smallpox, vaccines have been a key tool for preventing disease. From smallpox to polio, diphtheria to COVID-19, vaccines have prevented more deaths from infectious disease than any other medical treatment.

Ever since 1796, when English scientist and physician Edward Jenner successfully inoculated an eight-year-old boy with cowpox to protect him from smallpox, vaccines have been a key tool for preventing disease. From smallpox to polio, diphtheria to COVID-19, vaccines have prevented more deaths from infectious disease than any other medical treatment. The show will be airing once a month, and I already have several episodes recorded. I am always interested in hearing pitches for new episodes, with guests who either have some weighty credentials in a given area (e.g., a biochemist who wants to address with me the question “What is life?”), or who have some demonstrable ability to speak about a topic in a compelling way (e.g., I’m recording an episode on friendship with someone whose credentials in this area are that he is my old old friend and I know him to be an excellent raconteur). [3QD Editor’s Note: the friend mentioned here happens to be yours truly—S. Abbas Raza]

The show will be airing once a month, and I already have several episodes recorded. I am always interested in hearing pitches for new episodes, with guests who either have some weighty credentials in a given area (e.g., a biochemist who wants to address with me the question “What is life?”), or who have some demonstrable ability to speak about a topic in a compelling way (e.g., I’m recording an episode on friendship with someone whose credentials in this area are that he is my old old friend and I know him to be an excellent raconteur). [3QD Editor’s Note: the friend mentioned here happens to be yours truly—S. Abbas Raza] The coronavirus sports a luxurious sugar coat. “It’s striking,” thought Rommie Amaro, staring at her computer simulation of one of the trademark spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2, which stick out from the virus’s surface. It was swathed in sugar molecules, known as glycans.

The coronavirus sports a luxurious sugar coat. “It’s striking,” thought Rommie Amaro, staring at her computer simulation of one of the trademark spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2, which stick out from the virus’s surface. It was swathed in sugar molecules, known as glycans. Over the past decade, autocrats around the world have perfected the technique of “managed” or “guided” democracy. In Belarus, Egypt, Russia, Uganda, Venezuela, and elsewhere, authoritarian leaders have held periodic elections to enhance their legitimacy but monopolized the media, restricted civil society, and manipulated state institutions and resources to ensure that they remained in power.

Over the past decade, autocrats around the world have perfected the technique of “managed” or “guided” democracy. In Belarus, Egypt, Russia, Uganda, Venezuela, and elsewhere, authoritarian leaders have held periodic elections to enhance their legitimacy but monopolized the media, restricted civil society, and manipulated state institutions and resources to ensure that they remained in power. The pack: that’s what they called it. A secret guide, discreetly passed to literary authors in need of money to sustain their ‘real’ art. Compiled by such an author, happy to share their experience of publishing erotica on Amazon, it offered advice to avant-garde writers keen to turn their hand to this lucrative genre. According to the pack, popular topics included:

The pack: that’s what they called it. A secret guide, discreetly passed to literary authors in need of money to sustain their ‘real’ art. Compiled by such an author, happy to share their experience of publishing erotica on Amazon, it offered advice to avant-garde writers keen to turn their hand to this lucrative genre. According to the pack, popular topics included: Vladimir Nabokov may be known to most people as the author of classic novels like “Lolita” and “Pale Fire.” But even as he was writing those books, Nabokov had a parallel existence as a self-taught expert on butterflies. He was the curator of lepidoptera at the

Vladimir Nabokov may be known to most people as the author of classic novels like “Lolita” and “Pale Fire.” But even as he was writing those books, Nabokov had a parallel existence as a self-taught expert on butterflies. He was the curator of lepidoptera at the  In 1990, not long after Jean-Marie Robine and Michel Allard began conducting a nationwide study of French centenarians, one of their software programs spat out an error message. An individual in the study was marked as 115 years old, a number outside the program’s range of acceptable age values. They called their collaborators in Arles, where the subject lived, and asked them to double-check the information they had provided, recalls Allard, who was then the director of the IPSEN Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. Perhaps they made a mistake when transcribing her birth date? Maybe this

In 1990, not long after Jean-Marie Robine and Michel Allard began conducting a nationwide study of French centenarians, one of their software programs spat out an error message. An individual in the study was marked as 115 years old, a number outside the program’s range of acceptable age values. They called their collaborators in Arles, where the subject lived, and asked them to double-check the information they had provided, recalls Allard, who was then the director of the IPSEN Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. Perhaps they made a mistake when transcribing her birth date? Maybe this