Christian Kleinbub at The Brooklyn Rail:

In the popular imagination, the name Leonardo da Vinci conjures many things. In traditional textbooks, he epitomizes the concept of the “Renaissance man,” capable of knowing and doing everything. Another view has it that he was a prototypical engineer and scientist—inventor of tanks, helicopters, self-perpetuating machines, and urban infrastructure—and thus the forerunner of much of what we deem essential in our supposedly secular, technology-driven world. Art historians generally describe him as the key figure in a new phase in European painting, attuned to the portrayal of psychology and the subjectivity of sight, all while exercising an unparalleled naturalism. But, despite these things, there has always been another image of Leonardo, one that associated him with hidden things, esoteric knowledge beyond common perceptions. In Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003), Leonardo figures as a guardian of a forbidden secret, keeping alive the dangerous knowledge that Christ married Mary Magdalene and had a child by her. In the context of Brown’s thriller, Leonardo is a knower of the unknown, a keeper of truths that must remain encrypted by means of his famous mirror writing. Because Leonardo’s secret could potentially overturn orthodox Christian beliefs, his perpetuation of it paradoxically meshes with his reputation as a harbinger of the modern world. Like a Nostradamus, he anticipates history, hiding the keys to understanding things that are beyond the grasp of his contemporaries and a challenge for more enlightened ages.

In the popular imagination, the name Leonardo da Vinci conjures many things. In traditional textbooks, he epitomizes the concept of the “Renaissance man,” capable of knowing and doing everything. Another view has it that he was a prototypical engineer and scientist—inventor of tanks, helicopters, self-perpetuating machines, and urban infrastructure—and thus the forerunner of much of what we deem essential in our supposedly secular, technology-driven world. Art historians generally describe him as the key figure in a new phase in European painting, attuned to the portrayal of psychology and the subjectivity of sight, all while exercising an unparalleled naturalism. But, despite these things, there has always been another image of Leonardo, one that associated him with hidden things, esoteric knowledge beyond common perceptions. In Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003), Leonardo figures as a guardian of a forbidden secret, keeping alive the dangerous knowledge that Christ married Mary Magdalene and had a child by her. In the context of Brown’s thriller, Leonardo is a knower of the unknown, a keeper of truths that must remain encrypted by means of his famous mirror writing. Because Leonardo’s secret could potentially overturn orthodox Christian beliefs, his perpetuation of it paradoxically meshes with his reputation as a harbinger of the modern world. Like a Nostradamus, he anticipates history, hiding the keys to understanding things that are beyond the grasp of his contemporaries and a challenge for more enlightened ages.

more here.

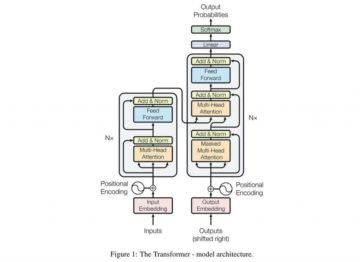

Last year I became fascinated with an artificial intelligence model that was being trained to write human-like text. The model was called GPT-3, short for Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3; if you fed it a bit of text, it could complete a piece of writing, by predicting the words that should come next.

Last year I became fascinated with an artificial intelligence model that was being trained to write human-like text. The model was called GPT-3, short for Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3; if you fed it a bit of text, it could complete a piece of writing, by predicting the words that should come next. Are you someone who enjoys the unsolicited opinions of strangers and acquaintances? If so, I can’t recommend cancer highly enough. You won’t even have the first pathology report in your hands before the advice comes pouring in. Laugh and the world laughs with you; get cancer and the world can’t shut its trap. Stop eating sugar; keep up your weight with milkshakes. Listen to a recent story on NPR; do not read a recent story in Time magazine. Exercise—but not too vigorously; exercise—hard, like Lance Armstrong. Join a support group, make a collage, make a collage in a support group, collage the shit out of your cancer. Do you live near a freeway or drink tap water or eat food microwaved on plastic plates? That’s what caused it. Do you ever think about suing? Do you ever wonder whether, if you’d just let some time pass, the cancer would have gone away on its own?

Are you someone who enjoys the unsolicited opinions of strangers and acquaintances? If so, I can’t recommend cancer highly enough. You won’t even have the first pathology report in your hands before the advice comes pouring in. Laugh and the world laughs with you; get cancer and the world can’t shut its trap. Stop eating sugar; keep up your weight with milkshakes. Listen to a recent story on NPR; do not read a recent story in Time magazine. Exercise—but not too vigorously; exercise—hard, like Lance Armstrong. Join a support group, make a collage, make a collage in a support group, collage the shit out of your cancer. Do you live near a freeway or drink tap water or eat food microwaved on plastic plates? That’s what caused it. Do you ever think about suing? Do you ever wonder whether, if you’d just let some time pass, the cancer would have gone away on its own? A major focus of modern medicine is treating existing conditions, but a promising approach is to try to detect elevated susceptibility to a condition before it becomes a diagnosable disease. “The pre-disease state, where someone has increased susceptibility to developing diseases, such as cancer, is widely considered the best period for intervening,” explains Yoshinori Kono, project leader at Kewpie. “Treating disease is important, but preventing disease before it strikes will reduce healthcare costs and improve quality of life.”

A major focus of modern medicine is treating existing conditions, but a promising approach is to try to detect elevated susceptibility to a condition before it becomes a diagnosable disease. “The pre-disease state, where someone has increased susceptibility to developing diseases, such as cancer, is widely considered the best period for intervening,” explains Yoshinori Kono, project leader at Kewpie. “Treating disease is important, but preventing disease before it strikes will reduce healthcare costs and improve quality of life.”

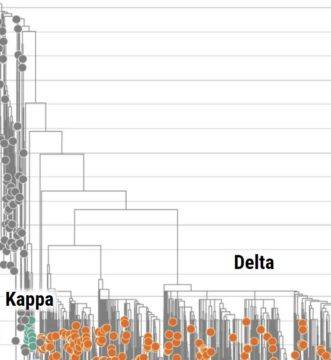

Edward Holmes does not like making predictions, but last year he hazarded a few. Again and again, people had asked Holmes, an expert on viral evolution at the University of Sydney, how he expected SARS-CoV-2 to change. In May 2020, 5 months into the pandemic, he started to include a slide with his best guesses in his talks. The virus would probably evolve to avoid at least some human immunity, he suggested. But it would likely make people less sick over time, he said, and there would be little change in its infectivity. In short, it sounded like evolution would not play a major role in the pandemic’s near future.

Edward Holmes does not like making predictions, but last year he hazarded a few. Again and again, people had asked Holmes, an expert on viral evolution at the University of Sydney, how he expected SARS-CoV-2 to change. In May 2020, 5 months into the pandemic, he started to include a slide with his best guesses in his talks. The virus would probably evolve to avoid at least some human immunity, he suggested. But it would likely make people less sick over time, he said, and there would be little change in its infectivity. In short, it sounded like evolution would not play a major role in the pandemic’s near future. Exactly one year ago, I did not die from poisoning by a chemical weapon, and it would seem that corruption played no small part in my survival. Having contaminated Russia’s state system, corruption has also contaminated the intelligence services. When a country’s senior management is preoccupied with protection rackets and extortion from businesses, the quality of covert operations inevitably suffers. A group of FSB agents applied the nerve agent to my underwear just as shoddily as they incompetently dogged my footsteps for three and a half years – in violation of all instructions from above – allowing

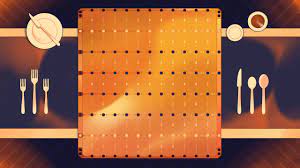

Exactly one year ago, I did not die from poisoning by a chemical weapon, and it would seem that corruption played no small part in my survival. Having contaminated Russia’s state system, corruption has also contaminated the intelligence services. When a country’s senior management is preoccupied with protection rackets and extortion from businesses, the quality of covert operations inevitably suffers. A group of FSB agents applied the nerve agent to my underwear just as shoddily as they incompetently dogged my footsteps for three and a half years – in violation of all instructions from above – allowing  Deep learning, the artificial-intelligence technology that powers voice assistants, autonomous cars, and Go champions, relies on complicated “neural network” software arranged in layers. A deep-learning system can live on a single computer, but the biggest ones are spread over thousands of machines wired together into “clusters,” which sometimes live at large data centers, like those operated by Google. In a big cluster, as many as forty-eight pizza-box-size servers slide into a rack as tall as a person; these racks stand in rows, filling buildings the size of warehouses. The neural networks in such systems can tackle daunting problems, but they also face clear challenges. A network spread across a cluster is like a brain that’s been scattered around a room and wired together. Electrons move fast, but, even so, cross-chip communication is slow, and uses extravagant amounts of energy.

Deep learning, the artificial-intelligence technology that powers voice assistants, autonomous cars, and Go champions, relies on complicated “neural network” software arranged in layers. A deep-learning system can live on a single computer, but the biggest ones are spread over thousands of machines wired together into “clusters,” which sometimes live at large data centers, like those operated by Google. In a big cluster, as many as forty-eight pizza-box-size servers slide into a rack as tall as a person; these racks stand in rows, filling buildings the size of warehouses. The neural networks in such systems can tackle daunting problems, but they also face clear challenges. A network spread across a cluster is like a brain that’s been scattered around a room and wired together. Electrons move fast, but, even so, cross-chip communication is slow, and uses extravagant amounts of energy. W

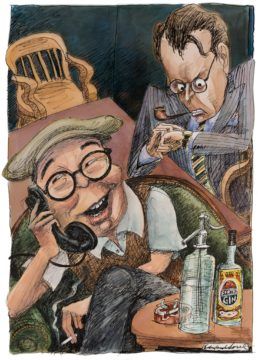

W In the rat-infested trenches of France, Raymond Chandler became an alcoholic, and stayed one. In 1932, after booze had gotten him fired from a cushy job, he resolved to cut down on the gin and become a novelist. He began by selling hard-boiled detective yarns to the pulpy magazine Black Mask, then later sold his first novel, “The Big Sleep,” to Alfred A. Knopf. In 1943, Chandler’s third novel, “The High Window,” was read by the Paramount director Billy Wilder. He liked the way Chandler wrote dialogue, and offered him a contract of $750 a week for 10 weeks to work with him on a screenplay for “Double Indemnity,” James M. Cain’s novel. Chandler had never written for the screen, and didn’t like the idea of being subservient to a young Austrian-born Jew who had written dozens of screenplays in Berlin and Hollywood. But Chandler was broke, and had a sick wife to care for. He signed up.

In the rat-infested trenches of France, Raymond Chandler became an alcoholic, and stayed one. In 1932, after booze had gotten him fired from a cushy job, he resolved to cut down on the gin and become a novelist. He began by selling hard-boiled detective yarns to the pulpy magazine Black Mask, then later sold his first novel, “The Big Sleep,” to Alfred A. Knopf. In 1943, Chandler’s third novel, “The High Window,” was read by the Paramount director Billy Wilder. He liked the way Chandler wrote dialogue, and offered him a contract of $750 a week for 10 weeks to work with him on a screenplay for “Double Indemnity,” James M. Cain’s novel. Chandler had never written for the screen, and didn’t like the idea of being subservient to a young Austrian-born Jew who had written dozens of screenplays in Berlin and Hollywood. But Chandler was broke, and had a sick wife to care for. He signed up. Chris Lehmann in The New Republic:

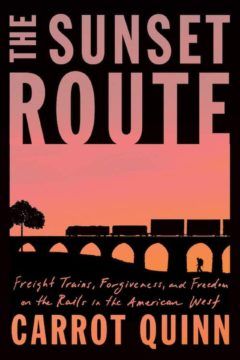

Chris Lehmann in The New Republic: THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?”

THE UNITED STATES has forgotten the hobo. We recognize the problem of homelessness, but the rootless rambler who steals rides on freight trains seems a relic of a long gone past. Even the word itself, hobo, is outdated. The same goes for the word tramp, which, if used at all tends to be for slut-shaming purposes. The term bum remains, but it, too, is derogatory, perhaps only acceptable as a verb, as in, “Can I bum a smoke?”