Daniel Davis in The Guardian:

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

Over the next few weeks, she Googled, read journal articles, and tried to become an expert patient in what was quite a rare genetic disorder. There wasn’t much to go on, and, not being a scientist herself, it was hard for her to evaluate what she did find. She learned that a link between mutations in this particular gene and connective tissue problems had only recently been discovered. A few years earlier this disease did not exist, or at least it had yet to be named. Over time, some details emerged. Nobody had ever seen her own family’s particular mutation in anyone else. So that meant it was very hard to know what to make of her situation. Her risk of a heart problem was surely increased, but nobody could say by how much.

More here.

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat. I

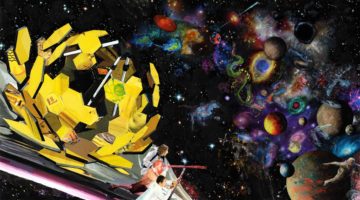

I To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine.

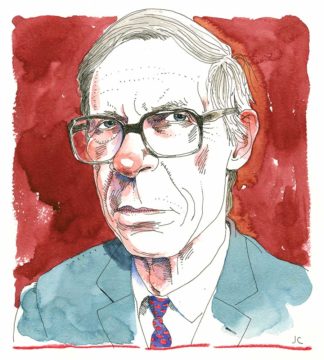

To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine. With its doctrine of fairness, A Theory of Justice transformed political philosophy. The English historian Peter Laslett had described the field as “dead” in 1956; with Rawls’s book that changed almost overnight. Now philosophers were arguing about the nature of Rawlsian principles and their implications—and for that matter were once again interested in matters of political and economic justice. Rawls’s terms became lingua franca: Many considered how his arguments, focused mostly on domestic or national issues of justice, might be applied to questions of international justice as well. Others sought to extend his theory’s set of political principles, while still others probed the limits of Rawls’s epistemology and the narrowness of his focus on individuals. A decade after A Theory of Justice appeared, Forrester notes, 2,512 books and articles had been published engaging with its central claims.

With its doctrine of fairness, A Theory of Justice transformed political philosophy. The English historian Peter Laslett had described the field as “dead” in 1956; with Rawls’s book that changed almost overnight. Now philosophers were arguing about the nature of Rawlsian principles and their implications—and for that matter were once again interested in matters of political and economic justice. Rawls’s terms became lingua franca: Many considered how his arguments, focused mostly on domestic or national issues of justice, might be applied to questions of international justice as well. Others sought to extend his theory’s set of political principles, while still others probed the limits of Rawls’s epistemology and the narrowness of his focus on individuals. A decade after A Theory of Justice appeared, Forrester notes, 2,512 books and articles had been published engaging with its central claims. Last week, the

Last week, the  Nancy Kathryn Walecki: So first of all, most people probably think of psychedelics in the context of the 1960s countercultural movements, when they were being used recreationally. So is using psychedelic drugs in psychiatric treatment a new idea?

Nancy Kathryn Walecki: So first of all, most people probably think of psychedelics in the context of the 1960s countercultural movements, when they were being used recreationally. So is using psychedelic drugs in psychiatric treatment a new idea? E

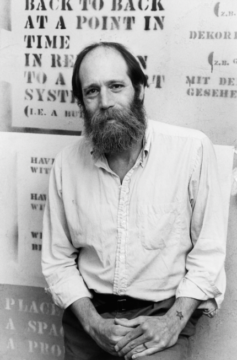

E Lawrence Weiner, a towering figure in the Conceptual art movement arising in the 1960s and who profoundly altered the landscape of American art, died December 2 at the age of seventy-nine. Known for his text-based installations incorporating evocative or descriptive phrases and sentence fragments, typically presented in bold capital letters accompanied by graphic accents and occupying unusual sites and surfaces, Weiner rose to prominence among a cohort that included Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Sol LeWitt. A firm believer that an idea alone could constitute an artwork, he established a practice that stood out for its consistent embodiment of his famous 1968 “Declaration of Intent”:

Lawrence Weiner, a towering figure in the Conceptual art movement arising in the 1960s and who profoundly altered the landscape of American art, died December 2 at the age of seventy-nine. Known for his text-based installations incorporating evocative or descriptive phrases and sentence fragments, typically presented in bold capital letters accompanied by graphic accents and occupying unusual sites and surfaces, Weiner rose to prominence among a cohort that included Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Sol LeWitt. A firm believer that an idea alone could constitute an artwork, he established a practice that stood out for its consistent embodiment of his famous 1968 “Declaration of Intent”: “Stephen’s story is well documented, the pain of it. Now here he was writing a beautiful song for the mother and wanting to write the son’s part. I had a relationship with my mother that I don’t think was as difficult, it had a little more grace, but it was challenging nonetheless. Stephen and I came to the conclusion that we never made the connection in the way we were searching for it. We kept passing by each other like ships in the night. A few days later, he hands me my part of the mother’s song. He’d taken our conversation and poeticised it. I got to be a teeny tiny part of what he was trying to say for this character. He wrote the most beautiful love song of two human beings trying to reach each other. That was the highlight of my entire professional life.”

“Stephen’s story is well documented, the pain of it. Now here he was writing a beautiful song for the mother and wanting to write the son’s part. I had a relationship with my mother that I don’t think was as difficult, it had a little more grace, but it was challenging nonetheless. Stephen and I came to the conclusion that we never made the connection in the way we were searching for it. We kept passing by each other like ships in the night. A few days later, he hands me my part of the mother’s song. He’d taken our conversation and poeticised it. I got to be a teeny tiny part of what he was trying to say for this character. He wrote the most beautiful love song of two human beings trying to reach each other. That was the highlight of my entire professional life.” Brian Callaci in The Boston Review:

Brian Callaci in The Boston Review: Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka: The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on

The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on